Flag, An American Biography by Marc Leepson

Marc Leepson has written an engaging book on a familiar topic about which a great deal is known that isn’t true.  A journalist and historian, Leepson’s purpose is to discover where fable and fact intersect. Because he writes with humor and irony, readers absorb 266 pages of what otherwise would be more than most people want to know about his subject.

Marc Leepson has written an engaging book on a familiar topic about which a great deal is known that isn’t true.  A journalist and historian, Leepson’s purpose is to discover where fable and fact intersect. Because he writes with humor and irony, readers absorb 266 pages of what otherwise would be more than most people want to know about his subject.

Leepson follows the evolution of the American flag from almost an afterthought to powerful national icon. He traces its transformation through legendary military battles, national holidays, political campaigns, famous paintings, Broadway musicals, hot wars, cold wars, controversial wars, and national tragedies. It is a fascinating journey.

The very first American flag, although at the time it had no official standing, was hoisted on January 1, 1776 by order of George Washington to mark the birth of the Continental Army. The Continental Colors had thirteen alternating red and white stripes and featured the British Union Jack in the upper left corner.

It is generally accepted that the thirteen stripes represented the colonies and the Union Jack the rebellious colonists’ loyalty to the British crown, although not its Parliament’s policies.

At this stage of the rebellion, six months before the Declaration of Independence was signed, it was a fairly accurate expression of rebel sentiments.

It became the de facto official flag of American Naval Forces, although it was flown on land as well.

No one knows who was responsible for the design, but it turned out to be a bad idea. When British troops saw it they thought the Union Jack signaled that the Americans were surrendering.

Although George Washington complained about the confusion, it took until June 14, of 1777 until Congress got around to legislating what the new country’s flag ought to look like: “Resolved, that the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.â€

At the time, civilians didn’t fly the flag. Most probably did not know what it looked like. It was flown mainly on commercial and navy ships and over American military installations. The flag as a symbol of the nation didn’t play much of a role during the revolutionary and post revolutionary years.

Congress did not specify the exact order of the stars or the flag’s proportions. As a result, during the next 135 years how flags looked depended on the imaginations of those who generated them. The fact that flags were hand stitched added to the variety.

Which brings up one of the fables. Betsy Ross was an established seamstress in Philadelphia, (among at least 17 other upholsters and flag makers), who produced ensigns for ships. However, according to Leepson and other researchers, there is not a shred of evidence that she made the first American flag; that George Washington ever visited her shop; or that they were even acquainted, US postage stamps and Hollywood movies not withstanding.

Nor is it true that Washington’s troops flew the Stars and Stripes at the battles of Trenton and Princeton in December of 1776 or January of 1777 respectively. We have artistic license to thank for these fables.

In the Emanuel G. Leutze painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware that hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, future president Lt. James Monroe is depicted holding the flag. John Turmbull’s paintings in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda of the battles of Saratoga and Yorktown also prominently feature American flags.

However, Congress did not declare the official flag until June of 1777 and never supplied it to Washington’s army. The paintings were done well after the fact and Turmbull admitted that his desire to commemorate these events heroically trumped historical accuracy.

Although Vermont became the 14th state in March of 1791, and Kentucky entered the union in 1792, it wasn’t until 1793 that Congress took up the matter of changing the flag to incorporate the new states. After some debate, legislation passed on January 13, 1795 prescribed that a fifteen star, fifteen stripe flag would be the nation’s official emblem. It would be the official flag for the next 23 years.

Although Vermont became the 14th state in March of 1791, and Kentucky entered the union in 1792, it wasn’t until 1793 that Congress took up the matter of changing the flag to incorporate the new states. After some debate, legislation passed on January 13, 1795 prescribed that a fifteen star, fifteen stripe flag would be the nation’s official emblem. It would be the official flag for the next 23 years.

The war of 1812 figures prominently in the flag’s iconography. The battle of Fort McHenry in 1814 began the popularization of the flag. Or more accurately, it was Francis Scott Key’s poem about the battle. On Sept. 4, 1814, Key sailed a 60 ft. sloop under a flag of truce to meet with commanders of the British fleet in Chesapeake Bay. He was there to obtain the release of his friend Dr. William Beanes, a civilian, who had been taken prisoner.

Key obtained his friend’s release but they were not permitted to leave until after the British attack on Baltimore. That was how Key, at anchor aboard his sloop in Baltimore Harbor, got a front row seat at the British bombardment of the Fort. The rest of the story is too well known to require repeating. Suffice it to say that “The Star Spangled Banner†of Key’s vivid description, followed by its being set to music, significantly contributed to the flag’s becoming a revered symbol of American patriotism.

When the 15 star and striped Star Spangled Banner flew over Fort McHenry the Union had increased to 18 states (Tennessee, 1796, Ohio, 1803, and Louisiana, 1812). However, Congress showed little interest in updating the flag. When the 19th state, Indiana, entered the Union in 1816, committees were appointed to study the matter. Debate ensued but no action was taken (some things don’t change) until December of 1817 when Mississippi became the 20th state. The nation’s Third and final Flag Resolution was signed into law on April 4, 1818. It mandated that one star be added to the American flag “on the admission of every new state into the union†and that the star would be added “on the fourth of July then next succeeding such admission.†Because the 1818 law did not specify the arrangement of the stars or the flag’s dimensions, American flags varied greatly in size, shape and design for decades.

When the 15 star and striped Star Spangled Banner flew over Fort McHenry the Union had increased to 18 states (Tennessee, 1796, Ohio, 1803, and Louisiana, 1812). However, Congress showed little interest in updating the flag. When the 19th state, Indiana, entered the Union in 1816, committees were appointed to study the matter. Debate ensued but no action was taken (some things don’t change) until December of 1817 when Mississippi became the 20th state. The nation’s Third and final Flag Resolution was signed into law on April 4, 1818. It mandated that one star be added to the American flag “on the admission of every new state into the union†and that the star would be added “on the fourth of July then next succeeding such admission.†Because the 1818 law did not specify the arrangement of the stars or the flag’s dimensions, American flags varied greatly in size, shape and design for decades.

The Mexican American war was the first war that American troops carried the Stars and Stripes into battle. Future president General Zachary Taylor flew the 28 star flag (Illinois, Alabama, Maine, Missouri, Arkansas, Michigan, Florida, Texas) when his men defeated the Mexican army of the North. The Mexican War also boosted public perception of the flag as a symbol of valor, patriotism, and victory. While still used primarily by the government and the military, it now began appearing in advertising and on promotional items.

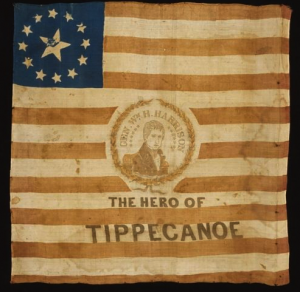

It first became part of a national political campaign during the presidential election of 1840 when William Henry Harrison incorporated it to build his image as is a war hero and inscribed his name on Stars and Stripes banners.

It first became part of a national political campaign during the presidential election of 1840 when William Henry Harrison incorporated it to build his image as is a war hero and inscribed his name on Stars and Stripes banners.

The Civil War also increased the importance of the American flag. As one flag historian noted, “When the stars and stripes went down at Sumter, they went up in every town and county in the loyal states.†The official American flag at the onset of the Civil War contained 34 stars, (Iowa, Wisconsin, California, Minnesota, Oregon, Kansas) despite the secession of 11 states. Lincoln insisted that the rebellious states remained part of the union.

When Philadelphia hosted the huge Centennial Exhibition of 1876, it produced a profusion of American flags. Artist Archibald Willard, painted “The spirit of ’76,†which was displayed in the Exhibition’s Memorial Hall. Willard followed the example of earlier artists by inserting a flag where it never was. His painting shows three heroic figures marching under clouds of battle smoke and a Continental Army flag bearer carrying the “Betsy Ross†flag (with thirteen stars arrayed in a circle in the upper left corner) marching behind them. In the foreground lies a wounded soldier who rises on his elbow to salute. It was a sensation! Never mind that the Continental Army did not fly the Stars and Stripes. The painting, now displayed at Abbot Hall in Marblehead, MA, remains popular today and lends credence to the fable that Washington’s army marched under the Stars and Stripes. You just can’t keep a good story down.

The flag and Flag Day were woven into the 1896 presidential election campaign of Republican candidate William McKinley. Thousands of flags, flag buttons and miles of flag bunting decorated his campaign appearances. The campaign declared October 31 National Flag Day and Republican Party stalwarts across the country responded with massive events just three days before the election. The message was that voting Republican was the patriotic thing to do.

The flag and Flag Day were woven into the 1896 presidential election campaign of Republican candidate William McKinley. Thousands of flags, flag buttons and miles of flag bunting decorated his campaign appearances. The campaign declared October 31 National Flag Day and Republican Party stalwarts across the country responded with massive events just three days before the election. The message was that voting Republican was the patriotic thing to do.

Oklahoma entered the union in 1907 making it the 46th state, following West Virginia, Nevada, Nebraska, Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming and Utah. By this time it was determined that federal agencies were flying no fewer than sixty-six different versions of the American flag prompting the federal government to appoint a special committee to determine how the 46 star flag should look. Recommendations were made, but when New Mexico and Arizona became 47 and 48 the panel had to go back to the drawing board. The final recommendation was that the stars be arranged in six horizontal even rows of eight stars each with one point of each star facing upward.

On June 24, 1912, President William Howard Taft signed an executive order setting out the arrangement for the 48 stars. Â It was the first time since the birth of the stars and stripes in 1777 that a president officially clarified what the American flag should look like, and what dimensions the government would accept for its flags.

Americans have a unique emotional attachment to their flag and it is inexorably woven into the nation’s history. It’s all in Leepson’s book: the raising of the flag atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima during WWII, Viet Nam era flag burnings, Neil Armstrong’s planting of the flag on the Moon, the damaged flag pulled from the debris of the World Trade Center and much more.

Americans have a unique emotional attachment to their flag and it is inexorably woven into the nation’s history. It’s all in Leepson’s book: the raising of the flag atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima during WWII, Viet Nam era flag burnings, Neil Armstrong’s planting of the flag on the Moon, the damaged flag pulled from the debris of the World Trade Center and much more.

Finally, the design of the current 50 star flag (Alaska and Hawaii) is one of the more intriguing flag stories and this reviewer isn’t going to tell it. Anyone wanting to know the details will have to read Leepson’s book. You will be glad you did.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

7 comments

Great article. The bombardment of Fort McHenry was September 13/14. Not September 4.

[Reply]

My fault for not clarifying. Key actually met with the British on September 5. They were allowed to return to the sloop under guard and a British frigate towed them toward Baltimore. . They were at anchor in the harbor four more days where they witnessed the fighting including the barrage during the stormy night of September 13-14.

[Reply]

Ok, so Francis Scott Key was on a British ship for over a week before being released by the British after the bombardment of Fort McHenry. I didn’t know that. Thanks.

[Reply]

Also worth noting that the flag which was to become “The Star Spangled Banner” was constructed by Mary Pickersgill in Baltimore – a widow caring for her daughter, mother, nieces, and servants. She was a remarkable entrepreneur and deserving of every bit of praise and notice that is heaped upon Mrs. Ross. Let us no longer bypass her name from the history of the flag.

[Reply]

You are right. Thanks for helping to set the record straight. Here is what Leepson says about her: “No flag sewn by Betsy Ross is know to exist today. But the flag that inspired the National Anthem, the flag known as the Star-Spangled Banner, resides in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington. There is, moreover, indisputable evidence showing that Mary Young Pickersgill of Baltimore was the creator of that enormous and enormously influential, thirty-by forty-two-foot, fifteen -star, fifteen-stripe flag.”

[Reply]

Dale Frances Scot Key and his Dr. Friend were on the 60 foot sloop that the British towed to the harbor during the bombardment. Not a British naval vessel.

[Reply]

Please refer to comment 2 above, my response to another comment, for clarification. Key and Dr. Friend met with the British aboard the British navel vessel but were aboard the sloop during the bombardment.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment