George Washington A Life by Ron Chernow

Ron Chernow’s new biography of George Washington succeeds in presenting a fresh look at the father of our country. Unlike some other biographies reviewed on this site, this one presents an image of Washington that is more than just a narrative. In the book’s prelude, Chernow states that he based this 800+ page tome on a “close reading” of “sixty volumes of letters and diaries published” thus far in the new edition of The Papers of George Washington. Collating and organizing these papers is a massive project that was started at the University of Virginia in 1968 and continues today.

Ron Chernow’s new biography of George Washington succeeds in presenting a fresh look at the father of our country. Unlike some other biographies reviewed on this site, this one presents an image of Washington that is more than just a narrative. In the book’s prelude, Chernow states that he based this 800+ page tome on a “close reading” of “sixty volumes of letters and diaries published” thus far in the new edition of The Papers of George Washington. Collating and organizing these papers is a massive project that was started at the University of Virginia in 1968 and continues today.

In accessing this treasure trove of research, Chernow gained a lot of insight into the workings of Washington’s mind, his personality, and his faults. By the end of the book, the reader is left feeling that he “knows” Washington.

Like most biographies, Chernow works chronologically through Washington’s life. He doesn’t spend a whole lot of time on his subject’s boyhood but does introduce Washington’s complicated relationship with his mother.

Mary Ball Washington was not a pleasant woman, and though Washington was exactingly correct in fulfilling his obligations to her throughout her life, he never felt much filial warmth. An early example of the color that Chernow is able to add to his chronicle is in the recounting of a telling exchange of letters between Washington and his mother, in early May of 1755. At the time, Washington was serving on General Braddock’s staff at the frontier town of Winchester. He wrote to her, proud of his appointment and she, nonplussed, asked him to bring her some butter. Throughout her life, she played the martyr and never bothered to acknowledge her son’s accomplishments, instead even going so far as to accuse him of leaving her destitute. He didn’t, but there was no love lost between them. Chernow’s chronicle of Washington’s relationship with his mother differs markedly from that presented in Life of Washington by Anna Reed.

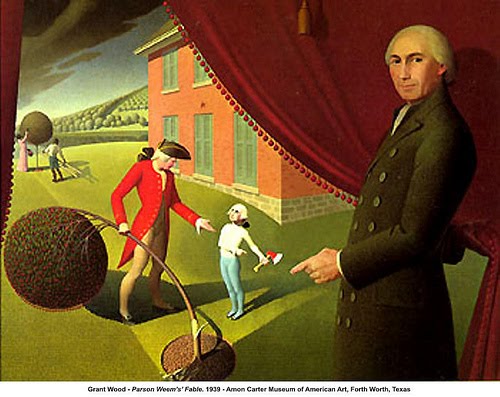

Chernow’s biography provides a multi-dimensional look at George Washington that provides insight into the complexities of his character and uniquely illustrates his struggles and growth as a human being. This differs from the picture that too many now have in their minds of the fully formed Washington, already old and white haired, even in boyhood.

Chernow’s Washington is a real human being. He is a robust virile man with almost legendary self control. Washington’s letters to Sally Fairfax, the wife of a close friend, reveal a romantic, flirtatious character that few today would associate with the Washington we read about in school text books. There is an interesting parallel between Washington and Hamilton in this regard. As a young man Hamilton was enamored with his wife’s sister in a similar way. Both Washington and Hamilton went out of their way to be frank in their affections, but to restrain their libidinous instincts. Washington was able to maintain his friendship with Sally Fairfax and her husband even after he wed Martha, including her in his correspondence and maintaining proper decorum. Chernow refers to George and Martha as “adult” in their sensibilities and relationship.

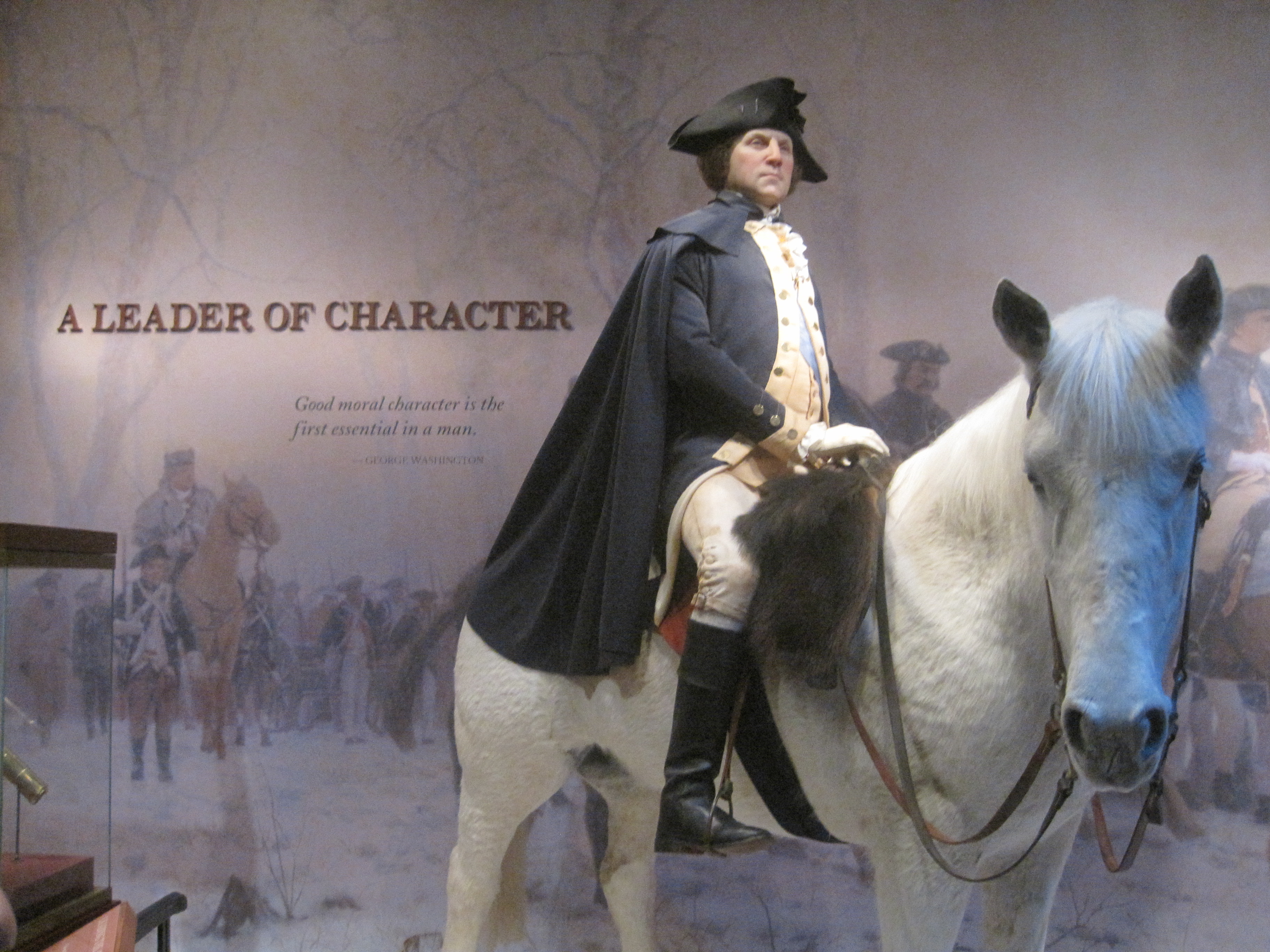

Although studiously proper, throughout his life, Washington had an eye for the ladies, and they for him. Throughout his letters, he references the ladies, with particular interest, who appeared at various receptions and parties. He was quite gallant and a graceful dancer. Contrast this with the dour, doughy-faced character on the dollar bill. The museum at Mount Vernon has several figures of Washington that were painstaking created using forensic science, measurements (for clothing orders), and actual hair samples taken at different times in Washington’s life. These figures took more than three years to make, and provide a striking picture of a Washington few would recognize today.

One thing that most accounts of Washington, and Chernow’s not excepted, agree on, is that Washington was a spectacular horseman, and gifted with unusual strength. His natural grace and serenity helped him throughout his life.

But it wasn’t only his physical presence and prowess that made Washington “the indispensable man”. Washington was fiercely ambitious at a time when overt displays of ambition were looked down upon. He learned to hide it and use “the gift of silence”. Some historians confuse his methodical and in-depth analysis of issues with being slow. He was anything but. While Washington always regretted his lack of formal education, he was very successful as an autodidact. Ultimately, he became a consummate politician, without peer.

Chernow shows how Washington applied the things he learned as young man, eager to advance in the British army. His irritation with the innate bias against colonial soldiers, and his grievances against British discrimination in regard to his pay and commission, later helped fuel his fire against them. He learned from his service in the French and Indian War how the British fought and what their weaknesses were. More importantly, he built his reputation as the premier military figure in the colonies.

At the age of 27 he augmented his military reputation with his entrance onto the political stage as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. It was here that he began to perfect the minimalist approach that added to his fame. Chernow tells some of the same anecdotes about Washington’s early political and military career that other biographers have, some which are new (at least to this reviewer), and some that have a decidedly different twist. For example, Chernow recounts the story of the old Indian’s prophecy about Washington’s indestructibility in battle, the story of Washington being struck and ultimately befriending the man he quarreled with (rather than challenging him to a duel), and of his nervous inaugural speech in the Virgina House of Burgesses.  Chernow adds observations on the minimalistic political style in comparison with that of Jefferson and also offers further insight through advice Washington gave his stepson on being a successful legislator. Throughout the book, Chernow provides a lot of color on Washington’s family life, in particular with his brood of surrogate children. Although he was devoid of natural children, Martha was a widow with 4, all of whom both she and George outlived. In addition to step-children and grandchildren, there was a succession of other youngsters taken in by the Washingtons. Relatives kept dying and leaving offspring in their care. Thus Washington had a rich family life, in spite of his apparent sterility.

Interestingly enough, the fact that he had no direct heir worked in Washington’s favor. It was viewed by many as a safeguard against a hereditary monarchy.

In addition to light shed on Washington’s character as a family man, Chernow briefly examines Washington’s religious life. In this he is in concord with Meacham’s assessment in his book American Gospel. Washington was certainly not a deist. He was extremely private in his worship and was mortified by ostentation more than by any distaste for Christianity.

Although Chernow doesn’t dwell on Washington’s religion, he provides a very complete and thorough look at Washington’s character through an examination of his letters and actions. One of the most prominent themes is that of Washington’s internal and external struggles with slavery. While the author makes no excuses for his subject in this area, he does a good job of explaining the complexities of the issue for Washington. Throughout the book, he highlights the evolution of Washington’s views on “this peculiar species of property”. He includes the compromises that Washington had to make in accepting blacks into the army, his discussions with Lafayette, his relationship with his slaves, and his dependence on their labor for his livelihood. The picture he paints is not altogether flattering, but it is an honest one. Washington struggled with the issue for his entire public life, ultimately emancipating his slaves in his will, and making provision for their care and education to help them make the transition. He was the only Founder to do so and was extremely explicit in his final instructions to ensure that his wishes were obeyed. Again, Chernow doesn’t cut Washington any slack and views this as Washington’s major moral shortcoming. Washington’s self-interest won out over support for Henry Laurens’ abolitionist plans and represents a major missed historic opportunity.

Chernow is equally thorough in his coverage of Washington’s merits. Washington consistently tried to do the right thing for his country and frequently put the needs of the country ahead of his own. He accepted no remuneration for serving as General of the Continental army at a time when his finances were not good. He turned in his commission when many thought he should be king. He served as President of the Constitutional Convention and was elected unanimously as President, not once, but twice. Although the Constitution did not specify it, he set the precedent for stepping down after two terms, and astonished the world. The character and nature of the presidency was largely crafted by Washington. He set the bar for integrity that many of his successors would fail to reach.

There is an astonishing amount of information in this book, which is a delight to read for its sparkling prose and thoughtful analysis.  After relating the account of Washington’s death, Chernow sums up what Washington meant to his country.

George Washington possessed the gift of inspired simplicity, a clarity and purity of vision that never failed him. Whatever petty partisan disputes swirled around him, he kept his eyes fixed on transcendent goals that motivated his quest. As sensitive to criticism as any other man, he never allowed personal attacks or threats to distract him, following an inner compass that charted the way ahead. For a quarter century, he had stuck to an undeviating path that led straight to the creation of an independent republic, the enactment of the Constitution, and the formation of the federal government. History records few examples of a leader who so earnestly wanted to do the right thing, not just for himself, but for his country. Avoiding moral shortcuts, he consistently upheld such high ethical standards, that he seemed larger than any other figure on the political scene. Again and again the American people had entrusted him with power, secure in the knowledge that he would exercise it fairly and ably and surrender it when his term of office was up. He had shown that the president and commander in chief of a republic could possess a grandeur surpassing all the crowned heads of Europe. He brought maturity, sobriety, judgment, and integrity to a political experiment that could easily have grown giddy with its own vaunted success, and he avoided the backbiting, envy and intrigue that detracted from the achievements of other founders. He had indeed been the indispensable man of the American Revolution.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

5 comments

I think your review is excellent, and I love the pictures! I note that neither one of us said anything about George’s order for saltpeter when he got married….

[Reply]

Thanks! You are too kind. Neither did I refer to some of the books in their library or the letter to his friend who was getting married a little later in life….

[Reply]

Martin,

I have been waiting for this book to land on shelves for some time, and your excellent makes me all the more anxious to pick up a copy. Thanks for taking the time to give us all a little insight. Chernow is a fantastic writer, and you’ve done a most commendable job of describing his latest work.

Thanks!!

Regards,

Joel

[Reply]

Joel,

Thanks for your kind words. I always worry about even approaching justice to a fine work like Chernow’s. It contains so very much information that it’s almost impossible to adequately convey what an achievement it represents.

[Reply]

[…] Perhaps most important, he worked with Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson to convince George Washington to attend. Madison knew Washington’s Revolutionary renown would draw enough delegates […]

Leave a Comment