Berlin 1961 Kennedy, Khrushchev and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth

Berlin 1961

Berlin 1961

Kennedy, Khrushchev and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth

By

Frederick Kempe

Berlin 1961 tells the back-story of the Bay of Pigs, the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis. The author did a masterful job of weaving together recently declassified documents in the U.S., Germany and Russia and first person narratives for a previously untold account of these seminal events. Readers who remember these occurrences will be appalled at how the American public was deluded by government secrecy and a media smitten with a handsome, eloquent, but dangerously incompetent president.

Kennedy’s ill-advised Bay of Pigs invasion, using CIA-trained Cuban exiles, failed as a result of sloppy planning and the president’s refusal to provide needed U.S. resources for fear of irritating the Soviets. The far-reaching result of Kennedy’s timidity was that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev took his measure and determined that the new American president was weak and malleable. Both assessments were confirmed at the Vienna Summit in June of 1961 when Kennedy, again ignoring his advisors, became embroiled in a debate with Khrushchev he was unprepared to win.

Kennedy’s ill-advised Bay of Pigs invasion, using CIA-trained Cuban exiles, failed as a result of sloppy planning and the president’s refusal to provide needed U.S. resources for fear of irritating the Soviets. The far-reaching result of Kennedy’s timidity was that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev took his measure and determined that the new American president was weak and malleable. Both assessments were confirmed at the Vienna Summit in June of 1961 when Kennedy, again ignoring his advisors, became embroiled in a debate with Khrushchev he was unprepared to win.

In one staff member’s view, Kennedy should have said: “Now look, I want to say this perfectly straight. Get your bloody hands off Berlin or we’ll destroy you. Those were terms Khrushchev would have understood. The U.S. had such nuclear superiority that Kennedy did not need to take the Vienna beating.â€

The same staffer, after later examining the Vienna transcripts, disparaged Kennedy’s performance. “He was constantly talking about: We’ve got to find a way out. What can we do to reassure you? We don’t want you to distrust our motives. We are not aggressive.’’

The result of Kennedy’s placating was not a more tractable Khrushchev, but having determined there was small risk, the Soviet premier became increasingly aggressive.

Khrushchev’s purpose at the Vienna Summit was threefold: to neutralize Kremlin enemies who thought him insufficiently aggressive in dealing with the U.S.; to obtain concessions on Berlin which would prove them wrong; and stem the embarrassing out flow of refuges from the East German socialist paradise.

Kempe reports:

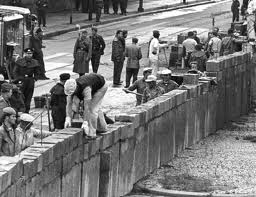

Between the establishment of the East German state in 1949 and 1961, one out of every six individuals–2.8 million people–had left as refugees. That total swelled to 4 million when one included those who fled the Soviet occupied zone between 1945 and 1949. The exodus was emptying the country of its most talents and motivated people.

If unstaunched the flood would cause the economic and political collapse of East Germany. An event the ruthless and ambitious East German leader Walter Ulbricht was determined to prevent. He was well aware that Moscow could not allow that to happen lest it have a domino effect on other captive peoples within the Soviet empire. Ulbricht used Kremlin impatience with “the German problem,†to ratchet up pressure on Khrushchev for a crack down to stop the exodus.

In his foreword to Berlin 1961, General Brent Scowcroft asks whether the Cold War would have ended sooner had Kennedy better managed his relationship with Nikita Khrushchev.

If Kennedy had handled Khrushchev differently at the Vienna Summit in June 1961, would the Soviet leader have balked at the notion of closing Berlin’s border two months earlier?

Or, on the other hand, as some have suggested; is it possible that we should regard Kennedy’s acquiescence to the communist construction of the wall in August 1961 as the best of bad alternatives in a dangerous world?’

That was not the view of General Lucius Clay of Berlin Airlift fame. Clay, in Berlin as Kennedy’s personal representative, had considerable experience calling the Soviet’s bluff. He did so (without orders) repeatedly and successfully in 1961 until forced to yield by an indecisive Kennedy who would not support a tougher posture.

That was not the view of General Lucius Clay of Berlin Airlift fame. Clay, in Berlin as Kennedy’s personal representative, had considerable experience calling the Soviet’s bluff. He did so (without orders) repeatedly and successfully in 1961 until forced to yield by an indecisive Kennedy who would not support a tougher posture.

In fact, as Kempe reveals, in Vienna Kennedy gave Khrushchev carte blanche to do what he liked regarding East Germany and other areas under Soviet control. That message was likely reinforced later in clandestine and imprudent contacts Between Bobby Kennedy and a Soviet agent who carried messages to and from Khrushchev. Eventual German reunification, a staple of American foreign policy, was cast aside. East Germany and the captive peoples of Eastern Europe were abandoned to their socialist fate. Kennedy’s only condition, one already guaranteed by agreement of the Allied powers in 1945, was that Western access to West Berlin not be compromised.

The result of these concessions was that the Cold War almost became hot on October 27 when, less than 100 yards apart, American and Soviet tanks faced each other at Checkpoint Charlie. The author’s riveting account of that night is guaranteed to have readers on the edge of their chairs, even those who remember the outcome.

As events escalated in Berlin, Kennedy increased troop spending and prepared a nuclear response plan that included estimated American losses. The American people, of course, were blissfully unaware of the latter.

Yet, as Kempe points out, Kennedy was “always a step behind the Soviets. When East German forces, with Soviet backing, closed down the border on August 13 with such remarkable speed and efficiency, the U.S. and its allies seemed to have been caught flatfooted.â€Â It appears that the art of “leading from behind†had already been mastered.

On August 12th as East Germans were preparing their midnight assault on the border and Dean Rusk was cabling U.S. Ambassador Walter Dowling his concerns about an East Berlin uprising in response to the danger of “the escape hatch being closed,†Kennedy was boating on Nantucket Sound. Rusk told Dowling, “It would be particularly unfortunate if an explosion in East Germany were based on the expectation of immediate military response.â€

A year later, In mid-August, as East Germans were being shot during desperate efforts to escape over the Berlin Wall, Soviet ships were landing in Cuba with the makings of a Soviet nuclear missile force.

Much to Khrushchev’s surprise. Kennedy took a harder line with the Soviets over Cuba than he had done in Berlin. It appears that Kennedy had learned, belatedly, that showing weakness only encouraged Khrushchev to push him harder. Khrushchev backed down, just as General Clay predicted he would have in Berlin, had he been challenged.

Kempe writes:

Though history would celebrate Kennedy for his management of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Khrushchev would not have risked putting nuclear weapons in Cuba at all if he had not concluded from Berlin in 1961 that Kennedy was weak and indecisive.

But Kennedy was never as uncompromising as the U.S. public believed. Brother Bobby and Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin reached an agreement on October 27th that the U.S. would withdraw its Jupiter nuclear missiles from Turkey.

From the vantage of hindsight we may conclude, as the author does, that the Berlin Wall could have, and should have been avoided and that had it been, the Cold War might have ended with the liberation of the people in the captive nations decades earlier. We can only conjecture as to the consequences for the Soviet Union had the exodus from East Germany continued.

From the vantage of hindsight we may conclude, as the author does, that the Berlin Wall could have, and should have been avoided and that had it been, the Cold War might have ended with the liberation of the people in the captive nations decades earlier. We can only conjecture as to the consequences for the Soviet Union had the exodus from East Germany continued.

Berlin 1961 examines the most significant confrontation of the Cold War and the events that stemmed from it. It is a far more complex story than this review can convey. Through his exhaustive research, Kempe provides unique insights into the individuals and forces that shaped the Cold War until the Berlin Wall came down on November 9, 1989 and the USSR dissolved in December of 1991.

This is also the story of a weak, indecisive and inexperienced president unprepared to engage a skilled and wily adversary. Steven Hayward, in The Politically incorrect Guide to The Presidents, said Kennedy was: “The only modern president with less preparation for office than Barack Obama.†But a worshipful press burnished the Camelot illusion while ignoring Kennedy’s actual performance. There are other similarities as well. Obama, like Kennedy, pursues a foreign policy shaped by the notion that making concessions to America’s adversaries can resolve conflicts rooted in who we are and what we believe as a nation.

The story of Obama’s secretive presidency has yet to be written. Although history may note that abandoning the Eastern Europe Missile-Shield Program to “re-set†our relationship with Russia has not resulted in a more cooperative Vladimir Putin.

Kempe adroitly captures the drama of events by having the individuals who participated tell the Berlin story. In addition to Khrushchev and Kennedy. they include German Chancellor Conrad Adenauer, West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk, unofficial advisor to Kennedy Dean Acheson, Walter Ulbricht, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, General Lucius Clay, and others. Juxtaposed with the key players are the imprisoned innocents and those whose lives were cut short by circumstances and decisions they were powerless to affect. Through their stories readers’ understand the horror and anger of the people of West Berlin as the barriers went up and Americans did nothing.

Berlin 1961 tells us that when America’s adversaries perceive this nation as unwilling to defend its interests, or careless of its sovereignty, the consequences, although impossible to fully calculate, will reach far beyond our own time.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

Good review. I bought it for my Kindle. Ought to be good reading on my trip to Istanbul and Spain.

[Reply]

We are so overwhelmed by the Kennedy narrative that a critical evaluation of his nearly 3 years in office has never broken through the curtain of romanticism. As an assassinated President, a certain gentleness is called for, but the rewriting of history to maintain a myth, only serves to mislead us at a steep cost. I can’t wait to read it.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment