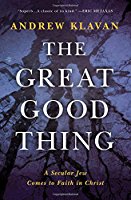

The Great Good Thing by Andrew Klavan

Sardonic and hilarious conservative novelist, screenwriter, columnist, and commentator Andrew Klavan has written an autobiographical account of his intellectual life.  The Great Good Thing covers only those aspects of Klavan’s life that relate to his metamorphosis from an anti-intellectual, secular Jew, to an intellectual Christian. Klavan was always obsessed with knowing the “why” of things. His was an intellectual conversion as much as a spiritual one. He devotes very little time to his work as a novelist, and none to his role as a political commentator. This is a book about the author’s efforts to make sense of western culture and to understand anti-semitism in its proper context. It is a book about finding God and finally Christ.

Sardonic and hilarious conservative novelist, screenwriter, columnist, and commentator Andrew Klavan has written an autobiographical account of his intellectual life.  The Great Good Thing covers only those aspects of Klavan’s life that relate to his metamorphosis from an anti-intellectual, secular Jew, to an intellectual Christian. Klavan was always obsessed with knowing the “why” of things. His was an intellectual conversion as much as a spiritual one. He devotes very little time to his work as a novelist, and none to his role as a political commentator. This is a book about the author’s efforts to make sense of western culture and to understand anti-semitism in its proper context. It is a book about finding God and finally Christ.

The truth resonates. And so, Andrew Klavan’s memoir is resonant.  The Great Good Thing a brutally honest book that chronicles Klavan’s journey to Christianity, through mental illness, and an honest search for truth. So, the reader might ask: what’s resonant about that?

Logic.

In the course of this journey, Klavan did a lot of reading, and realized, in Aristotelian fashion, that morality exists. Ironically, it was the Marquis de Sade who led Klavan to this particular epiphany.

Here at last, however, was an atheist whose outlook made complete logical sense to me from beginning to end. If there is no God, there is no morality. If there is no morality the search for pleasure and the avoidance of pain are all in all and we should pillage, rape, and murder as we please. None of this pale, milquetoast atheism that says “Let’s all do what’s good for society.” What is society to me? None of this elaborate game-theory nonsense where we all benefit from mutual sacrifice and restraint. That only works when no one is looking; then I’ll get away with what I can. If there is no God, there is no good, and sadistic pornography is scripture.

The truth is not affected by perception.  Truth is truth, regardless of our ability to perceive and understand it. This is one of the tenets of Klavan’s book and how he came to understand the God of Abraham’s words at the burning bush, “I AM THAT I AM.”  On the whole, man’s understanding of God doesn’t change His reality.

In reading Hamlet, Klavan picks up on the subtext the speech that Hamlet delivers while pretending to be insane.  “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Thus “Shakespeare had predicted post-modernism and moral relativism hundreds of years before they came into being!” Klavan points out that unlike the post-modernists and moral relativists,

Hamlet said these things when he was pretending to be mad. … Shakespeare was telling us, it seemed to me, Â that relativism was not just crazy, it was make-believe crazy, because even the people that proclaimed it did not believe it deep down. Â If, after all, there is no truth, how could it be true that there is no truth? Â If there is no absolute morality, how can you condemn the morality of considering my culture better than any other? Relativism made no sense, as Shakespeare clearly saw.

Klavan explains further,

But the opposite is also true. Â That is, if we concede that one thing is morally better than another, it can only be because it is closer to an Ultimate Moral Good, the standard by which it is measured. An Ultimate Moral Good cannot just be an idea. It must be, in effect, a personality with consciousness and free will. Â The rain isn’t morally good even though it makes the crops grow; a tornado that kills isn’t morally evil — though it may be an evil for those in its way. Â Happy and sad events, from birth to death, just happen, and we ascribe moral qualities to them as they suit us or don’t. But true, objective good and evil, in order to be good and evil, have to be aware and intentional. So an Ultimate Moral Good must be conscious and free; it must be God.

So we have to choose. Either there is no God and no morality whatsoever, or there is morality and God is real.

At this point in his life, Klavan reached a milestone.

After reading Sade, I abandoned atheism and returned to agnosticism. I couldn’t quite bring myself to follow my own logic to its conclusions. That is I couldn’t quite bring myself to accept the existence of God. But I knew the road to hell when I saw it and I chose to go home by another way.

He refers to this perception as the third of 5 epiphanies that led him to become a Christian. One of the others was the reality of love.

Unsurprisingly, Klavan came to this realization at the birth of his daughter.  It was an intellectual as well as metaphysical conclusion that helped him understand Genesis.

Sex, birth, marriage, these bodies, this life, they were all just representations of the power that had created them, the power now surging through my wife in this flood of matter, the power that had made us one: the power of love. Love, I saw now, was an exterior, spiritual force that swept through our bodies in the symbolic forms of eros, then bound us materially, skin and bone, in the symbolic moment of birth. Everything you were, everything you were going through — it was all merely living metaphor. Â Only the love was real.

This insight has a lot attached to it. It means that the metaphysical world is the only thing that really has meaning and that the physical world, the one we can see and touch is “merely living metaphor.” The Freudian, postmodern view declares just the opposite, that spiritual things are merely symbols of the flesh. Â Klavan, despite 5 years of psychiatric therapy, and a devotion to Freud, suddenly understood that Freud “had gotten it exactly the wrong way round. Our flesh was the symbol, it was the love that was real.”

This insight has a lot attached to it. It means that the metaphysical world is the only thing that really has meaning and that the physical world, the one we can see and touch is “merely living metaphor.” The Freudian, postmodern view declares just the opposite, that spiritual things are merely symbols of the flesh. Â Klavan, despite 5 years of psychiatric therapy, and a devotion to Freud, suddenly understood that Freud “had gotten it exactly the wrong way round. Our flesh was the symbol, it was the love that was real.”

It was Klavan’s own struggle with perceptions that helped him conclude that human observation is not as infallible as many believe.  “Why do you doubt your senses?” Jacob Marley asks Ebenezer Scrooge.  “Because,” Scrooge replies, “a little thing affects them.”

Why, after all, should the flesh be the ground floor of our interpretations? Why should we end our understanding at the level of material things? It’s just a prejudice really. the flesh is convincing. We can see it, feel it, smell it, taste it. It’s very there. It’s a trick of the human mind to give such presence the weight of reality. Men kill each other over dollar bills that are only paper because the paper has come to seem more real to them than the time and value it represents. In the same way, and for the same reason, people destroy themselves and everyone around them for sex: because sex has come to seem more real to them than the love it was made to express.

…

… I was beginning to realize there was a spiritual side to life, a side I had been neglecting in my postmodern mind-set. Strip that spirituality away and you were left with a kind of “realism” that no longer seemed to me very realistic at all.

Postmodern thinkers are obsessed with deconstruction. Â They “endlessly analyze our spiritual experiences of truth and beauty in order to get to the materialistic ‘reality’ underneath.”

It’s a flattering philosophy for intellectuals, no doubt. Endless analysis is what they’re good at. But the reductiveness and meaninglessness of the enterprise are creations of the enterprise itself. That is, you have to first make the assumption that material is the only reality before you can being to reason away the spirit.

Klavan doesn’t think much of postmodernism and not only because of its insistence on boiling things down to materialism.  In the course of Klavan’s intellectual journey he began, at first grudgingly, and then hungrily, to become a participant in what Mortimer Adler (and others) referred to as “The Great Conversation.” Here Klavan found that the internal lives of people, captured for posterity in written form can transcend time. He made this discovery toward the end his time in university when the “old school” liberal arts teachers were becoming seemingly powerless to address the postmodern onslaught. Whoever thought it would be necessary to defend beauty, truth and goodness? Those things simply are and are not subject to relativism – except as the product of pretended madness as in Hamlet. Klavan recounts a poignant anecdote that occurred in a class during a lecture on Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Charge of the Light Brigade. A product of the postmodern society stood up and indignantly questioned why this poem should be studied. “How can we even read this poem when all it does is glorify war?”

The poor professor’s face went blank. Clearly, she was a product of the old school. She studied literature because she loved literature not because she wanted to use it to preen herself on her own political virtue. She had never had to defend the beauty of beauty before, Â or the wisdom of wisdom. She smiled, and shrugged weakly, “I see what you mean,” she said.

At the back of the auditorium, I leapt to my feet, appalled. … Inarticulate with passion, I began to slap my open volume of Tennyson with the back of my hand, reading the opening lines aloud and saying, “Listen! Listen to this! Listen! ‘Half a league, Half a league onward — All in the valley of death rode the six hundred.’ You can hear the horses! You can — listen! — you can feel the courage and the madness, everything, it’s all there …” I babbled on like that for a few more seconds, and then dropped back into my seat blushing, feeling like an idiot.

This anecdote occurs toward the beginning of Klavan’s decades-long odyssey. Klavan’s conversion was not that of Saul on the rode to Damascus. Klavan’s journey was more like that of an archeologist who senses that there is something to unearth beneath a tell but does not know what it is.  As each artifact is excavated, he begins to formulate one hypothesis after another, discarding each until the final piece is revealed.  When all the parts are assembled, he has no choice but to accept the result as truth.

Klavan unearthed early pieces of the puzzle in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, although not at this point ready to accept the Christian aspects of the novel,

I knew beyond doubt that the essential vision of the novel was valid. The story’s rightness struck me broadside so that the journey of my heart changed direction. From the moment I read Crime and Punishment — though I did not know it, though it took me decades, thought I was lost on a thousand detours along the way — I was traveling away from moral relativism and toward truth, toward faith, toward God.

This resonance is what Klavan has himself achieved in The Great Good Thing.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

1 comment

I may order his book after I finish gift books. Sounds interesting! Ann H

[Reply]

Leave a Comment