Who Was Mr. Pierce?

The Pierce letter, loaned to me by a collector of postal history, stimulated my curiosity.  The collector handed me the letter and told me what he knew. I’m embarrassed to admit, my knowledge of Reconstruction was almost non-existent. His was more extensive, but he knew nothing of the people in the letter except what he was able to surmise. The collector figured they were carpetbaggers from the north who were getting their just desserts. While he admired Lizzie’s spunk (Burn away! I’ll dance on the ashes…), he thought that it was a delicious irony that while she got the candidate she wanted – Hayes – Reconstruction was ended anyway. He told me of the compromise of 1877 and the role that Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar  played  – and that he was from Mississippi. At the time, neither he nor I could make any connection between the Pierce’s and L.Q.C. Lamar. So, I decided to focus my efforts on Pierce.

The Pierce letter, loaned to me by a collector of postal history, stimulated my curiosity.  The collector handed me the letter and told me what he knew. I’m embarrassed to admit, my knowledge of Reconstruction was almost non-existent. His was more extensive, but he knew nothing of the people in the letter except what he was able to surmise. The collector figured they were carpetbaggers from the north who were getting their just desserts. While he admired Lizzie’s spunk (Burn away! I’ll dance on the ashes…), he thought that it was a delicious irony that while she got the candidate she wanted – Hayes – Reconstruction was ended anyway. He told me of the compromise of 1877 and the role that Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar  played  – and that he was from Mississippi. At the time, neither he nor I could make any connection between the Pierce’s and L.Q.C. Lamar. So, I decided to focus my efforts on Pierce.

I wondered who was “Mr. Pierce,†and what happened to him and Lizzie after the election?  There had to be a way to find out.

The first step I took was to see if I could find anything about the newspaper fires in Oxford that Lizzie wrote about. This was a dead end. It seemed that the non-Republican papers didn’t find it newsworthy! (In 1981 the collector had called Oxford to see if there were any records of the Pierces. He was told that they didn’t keep records of  “those people.”)

I went back to the letter. I read where Lizzie said that Mr. Pierce was in Washington testifying.  She wrote the letter in January of 1877. I wondered if perhaps there would be a record of Pierce in the Congressional Record.  I was pleased to discover that Google has scanned it in.  However, searching for the name Pierce in 1877 didn’t turn anything up.  I reread the letter again and noted that Lizzie alluded to Mr. Pierce as being part of “the Party”. I wondered if maybe there was some other kind of record, perhaps of the Republican party, and broadened my search. There in the Google results was a reference to a J.H. Pierce in something called “House documents, otherwise publ. as Executive documents: 13th congress.” This looked promising, upon inspection the second result was pretty definitive:

This had to be Mr. Pierce! The letter to Alphonso Taft reported exactly what Lizzie had written in her letter. Lizzie had referred to “Mr. Pierce” going to  Memphis to get information about the election.  Both letters also refer to the plot to do him bodily harm. Pierce was a United States Marshall in charge of law enforcement in the Mississippi district. (No wonder Lizzie said he could take care of himself.)

I kept digging to find out what might have become of J.H. Pierce and hoping to find a first name. Now, armed with more information than a last name, I was able to search for U.S. Marshal J.H. Pierce.

As it turned out, there were quite a few references. Mr. Pierce popped up in a book about Mississippi history, The Historical Roots of Yoknapatawpha by Don Harrison Doyle. There really was a connection between Pierce and Lamar! The book recounts a memorable exchange between U.S. Marshal James H. Pierce and L.Q.C Lamar during the 1871 Oxford Klan trial in which Lamar was the defense attorney.

The Oxford Klan Trial

Republican victory and political denomination only heightened the tension and violence in Lafayette County and across Mississippi. Northern Mississippi became notorious for white terrorism, which had become so pervasive that it seemed beyond the power of state law enforcement to quell. Congress passed the Klu Klux Klan Act in 1871 making violations of civil rights a federal crime. Gideon Wiley Wells, United States District Attorney for northern Mississippi, set out to vigorously prosecute and convict whites under the powers of the new act. The first case to be brought to trial under the new act opened in Oxford in June 1871, with L.Q.C. Lamar, former champion of secession, serving as lawyer for the defense of the accused Klansmen.

The Klan trial was under way in the U.S. Federal district court’s temporary quarters in Oxford when Lamar caused a terrific stir in the courtroom one afternoon.  He stood and claimed that a man in the courtroom had been stalking and threatening him. Judge Robert Hill ordered Lamar to sit down and be silent, but Lamar continued to speak and when a court deputy came toward him, Lamar picked up a chair and threatened to hit the deputy. Judge Hill grabbed the chair, and when U.S. Marshal James Pierce approached Lamar to calm him down, Lamar struck Pierce in the face, giving him “a pretty hard lick with his fist.” The blow knocked Pierce down and fractured his cheekbone. Lamar defied the court to arrest and imprison him.  People in the courtroom, including a crowd of University of Mississippi students, began to applaud Lamar. One report said the Klansmen on trial stood and cheered, stamped their feet, and let out rebel yells in uproarious approval of Lamar’s defiance. District Attorney Wells ordered one of the disorderly students arrested, but the student “did not move” and appeared as though “he intended to fight… nobody attempted to arrest him.” U. S. soldiers guarding the prisoners drew their guns. Someone went to call more soldiers. One raised his rifle, and one observer said he “thought [the soldier] probably would shoot … Everybody got still.”

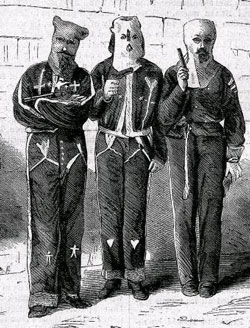

As this was the first and most significant application of the new act, Congress got a full report and a transcript of the trial. The picture of three Klansmen is included in the committee’s report.

As this was the first and most significant application of the new act, Congress got a full report and a transcript of the trial. The picture of three Klansmen is included in the committee’s report.

In the transcript, several conflicting versions of this event are given. ( It makes interesting reading – click on the text above for more information.) And lo and behold – the same Lamar that gave Mr. Pierce “a pretty hard lick”  was involved in the compromise that resulted in Hayes becoming president. Ironically, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, was also a resident of Oxford, Mississippi.

Mississippi History Now has this to say about L.Q.C. Lamar’s role in the compromise:

Lamar’s talent for reconciliation and compromise played a pivotal role in the controversial presidential election of 1876. The Democrat, Samuel Tilden, lost to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes despite having more popular votes and seemingly more votes in the Electoral College. Mississippi voted overwhelmingly for the Democrat Tilden. To resolve the dispute, Congressman Lamar, who would soon be Senator Lamar, helped set up a nonpartisan Election Commission, which chose Hayes as president.

Behind the scenes, Lamar was very involved in the bargaining and won many concessions for the South in exchange for supporting the Commission’s conclusions. Many Southerners were outraged that the election had in their eyes been stolen from the Democrat Tilden. They were more outraged that Lamar was involved in the deal. He faced a storm of opposition because most voters in Mississippi thought that a Hayes election would mean four more years of hardship and reconstruction. In hindsight, Lamar’s negotiating helped bring an end to Reconstruction under President Hayes’ administration.

This was of course, after he punched our very own Mr. Pierce in the face! Â (He didn’t seem inclined to compromise then.)Â Â In Doyle’s book we also find that Marshal Pierce was more than a U.S. Marshal and part owner of an Oxford newspaper (as Lizzie alludes to in her letter).

In 1872, Republican leader James Pierce led a group of some 400 black voters, four abreast, down North Street about noon, going toward the courthouse polls. On the square, a group of Democrats lined up a cannon, pretended to load it with cut up chain, and fired into the crowd of Republicans. Though it was actually, a blank charge, it had the desired effect of frightening the black voters into a hasty retreat. 88

This is probably the same canon that Lizzie described in her letter as having blown up.

Marshal Pierce was still hoping for a “fair election” in September of 1876 — If he got some troops to help him enforce it.

Attorney-General Alphonso Taft was the father of William Howard Taft, the 27th president of the United States. Pierce’s request was evidently denied.

The last thing that I found was a reference1 to a series of letters pertaining to the resignation of Mr. Pierce which he exchanged with Attorney General Charles Devens in the summer of 1877. Most of my questions were thus answered except the last one, what happened to Lizzie and James H. Pierce after the election. We can assume his resignation was due to the political changes taking place in Washington. It is also probably reasonable to assume that the Pierces returned to New York and a more hospitable environment.

Perhaps some reader will take up the search.

1Letters Received by the Attorney General, 1871–1884

88The reference in the book notes that this is not substantiated because Republican newspapers in town were burned down!

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

9 comments

Wow! Great research! This story was very fascinating to read. Especially that it gave such insight to the difficulty of the election process in the south during that era.

Very informative, thanks for the post.

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

February 16th, 2011 at 8:43 pm

Thanks! I’m glad that you enjoyed it. It was fun digging out some of the details. I’m hoping that someone with better researching skills than me can dig up what happened to James H. Pierce after he stopped being Marshall in Mississippi.

[WORDPRESS HASHCASH] The poster sent us ‘0 which is not a hashcash value.

[Reply]

It’s always interesting to meet people from our past, Martin. The interest is compounded, probably because we never seem to have the whole story. Your research has opened up a new perspective for me on the Reconstruction era based on the personal accounts of Mr. and Mrs. Pierce. The terror tactics that were employed by the white south to end reconstruction seem so surreal and unbelievable.

On the other hand the burning of Republican newspapers while the Democratic papers remained unscathed seems like the left (or were they the right at the time) has always attempted to silence speech that didn’t agree with them.

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

March 19th, 2011 at 11:05 am

I’m glad that you found the research interesting. The collector from whom I got the letter harbors an ardent dislike of reconstruction and carpetbaggers. Before we knew who Mr. Pierce was, we thought that they were just northern exploiters – he thought it ironic that Mrs. Pierce got the candidate she wanted but that reconstruction ended anyway. Obviously, with the additional information that Pierce was actually a person of some consequence and the fact that he supported L Q C Lamar, even after the latter socked him in the jaw, the collector’s views softened a bit. There’s always more to the story, it seems.

[Reply]

Cited by Don’t Give Up The Ship! on Lincoln and Secession.

Pierce went to Washington DC and was a government clerk.

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

May 24th, 2011 at 12:23 pm

Do you know more about what became of Marshal Pierce? From what I have collected at the National Archive, it looks like he took a job in the Treasury Department? Apparently, Charles Devens, the Attorney General suggested that he resign on July 10, 1877. He tells Pierce that he has “been authorized” to offer him a job by the acting Secretary of the Treasury as clerk.

I’ll post a follow up shortly.

[Reply]

Richie Burnette Reply:

December 26th, 2011 at 6:04 pm

Pierce plays a part in a story I am researching. L Q C Lamar did not represent the accused, but was in the courtroom. Lizzie Pierce did not go to DC, but remained in Oxford. J H Pierce married another woman in DC. Lizzie may not have been his wife.

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

December 26th, 2011 at 10:42 pm

I’d love to hear more, I hope you’ll contact us and let us know. I found some further correspondence at the National Archives where Pierce went to work for the Treasury.

Leave a Comment