An Interview With Marc Leepson, Author of Lafayette, The Idealist General

Mr. Leepson was kind enough to share an hour of his valuable time with me recently to discuss his latest book, Lafayette, Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General.

Mr. Leepson was kind enough to share an hour of his valuable time with me recently to discuss his latest book, Lafayette, Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General.

Section 1: Background On The Book

Martin: How did you end up doing the project?  Did you volunteer for the series. Were you contacted?  As someone who aspires to one day write, I’m interested in how this came about?

Marc: The book business is a strange and crazy thing. I finished my last book in the summer of ‘07 and my agent and I began talking about what the next book should be. I had several ideas and ended up writing 3 proposals – but for one reason or another, they didn’t go anywhere.  I’d rather not go into specifics about the topics, but they all were on U.S. History, two were biographies and one was straight history.

Anyway, my agent met the editor of 2 different series of books at Palgrave, The Great Generals and The World Generals. I ended up with a list of options and was asked to pick 3 generals from a list they provided and then asked to write snippet on each. I chose the Duke of Marlborough (on whom I’d written my Master’s Thesis), Clausewitz and Lafayette. They decided on Lafayette and then asked me to write the proposal! It was kind of backwards; normally you do the proposal first, but since this was my seventh book they kind of knew I could write.

Martin: How did you go about organizing your work? It is fairly condensed but complete.

Marc: In this particular series, there were guidelines and parameters for the series – 60,000 words.  That might seem like a lot to you, but it really isn’t much space in which to condense a man’s life. I ended up with way too much material.  I started the project by getting a jump start on where to look by reading the three latest biographies on Lafayette to use as road maps for the sources. I had less than 7 months to write the book. After a quick read, I went to the real grist of the research, a 5 volume set of letters to and from Lafayette during the American Revoluion from Cornell University Press – annotated.  I feel primary sources are preferable when writing something like this. Condensing someone else’s opinions wasn’t a direction I wanted to go.

Interesting enough, even the French letters were translated in the 5 volumes.  I also used Lafayette’s memoirs, although he continued to revise them throughout his life. Consequently, you have to check some of what he had to say! Overall, it was a good source, though.

Martin: Sounds like you used the same technique as Chernow. I recently finished reading his book on Washington. He went through the compiled letters and papers produced by the University of Virginia.

Marc: I haven’t finished Chernow’s book yet, but yes, I took a lot from Lafayette’s correspondence. It wasn’t uncommon for him to write 5 to 10 letters each day, as I mentioned in the book.

Martin: I am constantly surprised at how accessible the writings of this time were. How have you found accessibility?

Marc: Yes, they really knew how to write. Sometimes I had to struggle a little bit with handwriting, but on the whole their penmanship was surprisingly good. They usually took their time, and it showed. One of the greatest moments I had in writing the book was at Special Collections at Lafayette College. I got to hold the actual letter from Lafayette to Washington which accompanied the key to the Bastille that he sent to Washington. It was pretty cool.

Martin: Wow! I recently saw that at Mt. Vernon.

Marc: Yup, it’s there. Holding that letter was one of those really neat things for any historian.

Martin: Were you a Lafayette “fan†when you began researching the book?  What did you know before you started?

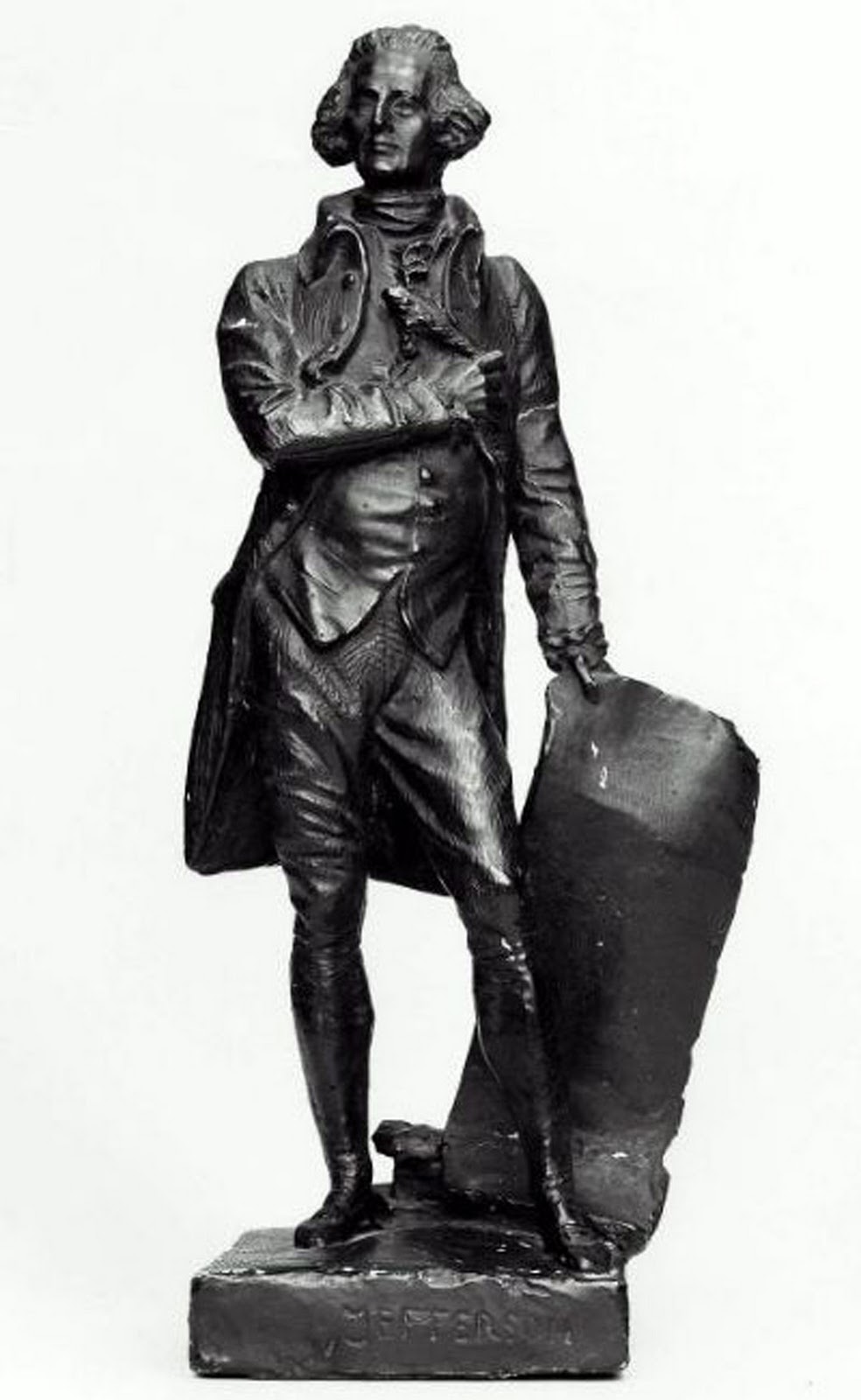

Marc: I have to admit, I didn’t know a lot about him before writing the book. I knew about Lafayette’s trip back to U.S. in 1824-25 from my earlier book Saving Monticello, and perhaps a few other things, but not in-depth.  For instance, Uriah Levy, who owned Monticello from 1834 to 1862, went to Paris in the late 1820’s to commission a full-size sculpture of Jefferson from one of the most famous sculptors of the time, David d’Angers. He went to see Lafayette because Lafayette had a painting of Jefferson to use as a model for the face. But, I learned a lot more in researching for this book.

Martin: Were you a Lafayette “fan†after you wrote the book? Did you, like many biographers, fall in love with your subject?

Marc: I have to admit that I did. How could you not? Don’t get me wrong, the man had his faults, but just look at the bare facts. He stuck to his principles throughout his life. He wanted a constitutional monarchy for France and stuck to that goal. He was an ardent republican with a small “r.â€Â There were one or two times when he could have a pulled a Napoleon, but he didn’t. He stuck to his beliefs often to his own monetary detriment, or even physical risk.

Martin: How did you go about finding and choosing the artwork featured in the book?

Marc: In any book of this type, the author is responsible for collecting the images. Librarians and archivists are the most valuable resource for any writer. In particular, at the Society of the Cincinnati, the head librarian was terrific. I got to sit down and go through their entire catalog of art. I also made extensive use of the Lafayette College Library. I’ve found that archivists and librarians are awesomely nice people. They are incredibly helpful.

Section 2: Connections and Rabbit Trails

Martin: In my own study, one of the most interesting things I have found is the myriad of connections that one begins to make in the course of reading multiple books covering the same people and events.  In Lafayette, I found a number of these “connections†– first it was Lafayette traveling to England and meeting some of his future adversaries face to face, and then it was in America, where he obviously was tight with Washington, but also with Monroe and many others (you provide a big list in the book.)

What was the most interesting connection to you? Â Who did Lafayette know that surprised you? Â Frederick the Great was one such for me.

Marc: For me, I guess it would be the fact that he knew 3 kings. He went to school with Louis the XVIII and Charles X, and he knew Louis XVI from his time at court. His relationship with Charles X was the most intriguing. I mentioned it in the book and you may have quoted it in your review, about the supposed last words Charles X uttered ashe was about to go into exile in England following the July Revolution of 1830.

Martin: Yeah, I had to laugh, it was something like “Everything would have been fine were it not for that “Damn old republican, Lafayette.â€

Marc: Yup. Lafayette also knew 5 presidents very well. Remember it was Monroe who was assigned to help the wounded Lafayette convalesce because he knew French. They were both about 20 years old and a lifelong friendship resulted from the experience.

Martin: I was surprised you left out Lafayette’s reunion with James Armistead?  How did you pick and choose?

Marc: Again, I would have liked to include more, but I needed to focus more on the military aspects of his life, given the nature of the series. And then there was the length limitation… I had to cut things to keep it in bounds.

Martin: What did you leave out of the book in terms of these interesting connections? Â What might you revisit, given the time?

Marc: There were some exciting things that I hated to omit, for instance there was an attempt to break him out of prison. It ended up being a comedy of errors, but they actually did get him out. I don’t know if you recall, but when Lafayette first came to American he landed off the coast of South Carolina and was met by a major Huger. It was Huger’s son, many years later, who decided he was going to break Lafayette out of prison. He was captured too, and there was quite a diplomatic kerfuffle about it, but he was finally let out of jail. Lafayette remained, though.

Martin: With regard to Washington at Yorktown, Chernow alludes to Washington’s dealing with the French Naval officers and suggests that in this one instance, Washington might have bent the facts a little.  Chernow says that Washington really had his heart set on New York, but that the French were pushing for Yorktown.  In the end Washington was convinced of the merits of the French plan and made it his own with a Herculean effort to build fake ovens to confuse the British they were staying, and then managing a logistic nightmare to get troops moved into position.  But, Washington kind of glosses over the idea that maybe he wasn’t so keen initially on attacking Yorktown.  Did you find any suggestion of this in your research?

Marc: No, I didn’t, not at the time I was writing the book, anyway. But since then, I’ve spoken with other historians, in particular a naval historian who said basically the same as Chernow.

Martin: Any comments or thoughts about Lafayette’s perception of the French Revolution in comparison with that of America’s?

Marc: While he might have been a radical in America, Lafayette was more of a moderate in France. He wasn’t advocating for the abolition of the monarchy. He wanted a constitutional monarchy. He was trying to be a moderate in the midst of a radical revolution. It was an untenable position for him. His time in America certainly had a huge impact on his political views and feelings, but he was, nonetheless a moderate in France.

Section 3: “Aha Moments†and Lessons for Today

Martin: What element of Lafayette’s character impressed you most?  For me, it was his humility and his willingness to sacrifice his own money and put himself in harm’s way.  Also his capacity to learn from his mistakes.

Marc: I think you’ve hit the nail on the head. Lafayette was young and impetuous, but a growing love for America grew out of his hatred for the British. He became a good tactical general – maybe not so great on the strategic side, he kept wanting to go attack Canada even when it was totally impractical! However, he stuck to his ideals. This wasn’t something I started with as a theme; it emerged after a lot of reading. He really believed in what he said he did. If you think about it, when he was invited to tour the United States in 1824, he was broke! He spent his money and his blood for what he believed. The Revolution cost him everything.

Martin: Why do you think he never emigrated to the United States, even after Napoleon took power?

Marc: I think that there were many reasons. I wondered the same thing when I was doing the research for the book. It may have been health related, especially after he was released from prison. It may have been Adrienne’s health or her family earlier on. You know he did come to America on 4 different occasions?

Martin: Yeah, that was a pretty incredible thing, considering that most of the trips were in war time.

Marc: And traveling across the Atlantic wasn’t a lot of fun!

Martin: What struck you as something that is lost today in comparing Lafayette’s character attributes with his modern counterparts?   Or does he have modern counterparts?

Marc: That’s a great question. You know I don’t think he had contemporary counterparts, let alone modern ones. He was an amazing person. He was pretty unique. You know, when the Society of Cincinnati began, the founders had a debate about whether or not to include foreign officers who served in the Continental Army. However, Lafayette was just in! It was a given. He was that unique, even in comparison with other Europeans that served in the American army. Remember, he was so popular in France, that after his return (after disobeying the king), he only got a slap on the wrist and was “imprisoned†in a palace for a few days. The king didn’t even dare discipline him – he was that popular.

Martin: What made Lafayette so enamored with America?  What made him such a “republican�

Marc: It started with his hatred of the British. He was born and bred to be a military man and to fight the British. Being so close to all these people in America, fighting for these principles, it crystallized. The Masonic connection also probably had an impact, too. Many of the American Founders were masons as well.

Martin:Â Ok, you’re a professional, I’m an amateur, What did I forget to ask you?

Marc: Well, you asked the number one question, about how the book came about, but you didn’t ask the number two question, which is “what’s your next book?â€

Martin: Actually, my next question was “What’s your next project?”

Marc: Hah! I don’t know. I have a few things in the works, we’ll have to see what my agent has to say about it!

Martin: Thank you very much for your time! I appreciate your generosity.

Marc: It was my pleasure.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

6 comments

Great interview. I felt I got to know Marc Leepson, as well as learn about Lafayette.

[Reply]

Great interview. I hope the book is just as good.

[Reply]

Enjoyed the interview. Mr. Leepson’s comments re: “myriad of connections” uncovered during research resonated. While writing my book on the 1949 Brooklyn Dodgers, I learned that volatile ex-manager Leo “The Lip” Durocher’s surname derived from the French word “roche”, indicating a forebear who resided in proximity to a rock. This led to a quip that most National League umpires believed instead that Leo lived underneath one.

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

March 29th, 2011 at 9:27 pm

Thanks. Mr. Leapson is a very nice guy. He was very kind and generous.

[WORDPRESS HASHCASH] The poster sent us ‘0 which is not a hashcash value.

[Reply]

I enjoyed the interview- especially the “nuts and bolts” about the process of getting a book deal and organizing so much material. It has to be a gargantuan task. Fun, interesting questions and back and forth with the author. Martin – you should have your own radio talk show!

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

March 30th, 2011 at 7:30 am

Thanks Jim, you’re too kind.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment