The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth Century America by Jay Sexton

Jay Sexton’s new book on the Monroe Doctrine is well researched and very informative. It is a look at a piece of political dogma that far outlived its creators and continued to have an effect on American diplomacy well into the 20th century. Sexton traces its origin in one of Monroe’s “State of the Union” addresses before Congress, and explains its grandiose rhetoric and more practical applications. The Monroe Doctrine is not a topic that many Americans know much about today. A vague notion of one of its many interpretations is all that is taught in schools. This reader was sadly ignorant of its applications and history – until this book came along.

Jay Sexton’s new book on the Monroe Doctrine is well researched and very informative. It is a look at a piece of political dogma that far outlived its creators and continued to have an effect on American diplomacy well into the 20th century. Sexton traces its origin in one of Monroe’s “State of the Union” addresses before Congress, and explains its grandiose rhetoric and more practical applications. The Monroe Doctrine is not a topic that many Americans know much about today. A vague notion of one of its many interpretations is all that is taught in schools. This reader was sadly ignorant of its applications and history – until this book came along.

The Monroe Doctrine was born of a compromise in James Monroe’s cabinet (in particular between John Quincy Adams and John C. Calhoun) in response to “the persistent danger of internal divisions” within the United States and the powerful impulse of nationalism – both brought to the fore by the impending dissolution of the Spanish Empire. It was a small part of Monroe’s 1823 message to Congress. In fact it was only 3 paragraphs in length or 954 words.  As Sexton shows, however, successive generations of American statesmen would consider it a keystone of American foreign policy. He explains:

The message of 1823 expressed at once the ambitions and insecurities of he United States. It reflected traditional distrust of Britain, but it also portended Anglo-American imperial collaboration. Most significantly, the statecraft of the 1820’s illustrated how foreign affairs could both strengthen and endanger the American union from within.

This is a recurring theme throughout the history of Monroe Doctrine. Sexton shows how different political factions used a few relatively ambiguous paragraphs of text to battle internal political constituencies, support others, and achieve foreign policy objectives. Throughout the 19th Century there were those who feared the interference of European monarchies in first, North America, and then in Cuba, the Caribbean, Central and South America. Simultaneously, many of these same political factions professed an ardent support for republican principles in governance. Complicating matters further was a desire not to be perceived as imperialistic like the bad old European powers. However, another doctrine with the same initials also factored into the policies of the new country — Manifest Destiny.

Sexton explains how different administrations twisted the meaning and interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine to fit their agendas. There was seemingly no contradiction in justifying the vast territorial expansion into Texas, Arizona, and California, with republican principles. This territory was “rightfully” and inevitably destined for the United States. There were many nuances behind support for or opposition to interpretation of Monroe’s words. At times, both sides of a political argument invoked their own interpretation with either a nationalist or republican spin on the meaning. During the period of time leading up to the Civil War, southern politicians only wanted expansion if it meant that new territories would continue the established practice of slavery. They invoked the doctrine in twisted ways in favor of intervention if not intervening would lead to the abolition of slavery and vice versa if it would not.

But, back in 1823, the famous Doctrine was concocted in response to concerns over both real and imagined meddling by the “Holy Alliance” of Europe.  France, Austria, Russian and Prussian asserted in the Troppau Circular of 1820, that they had the right “to suppress any revolutionary movement in Europe that they deemed a threat to their security.” When France intervened in Spain, in 1823, and reinstated the monarchy of Ferdinand VII, Washington became concerned that Spanish America might be the next target of the Troppau Doctrine.  After all, if France could do it in Spain, why couldn’t the same pretense be used for taking the same sort of action in Spain’s rebellious colonies?

Through the clever use of ambiguity and appeals to self-interest, the fledgling United States was able to hitch a ride on the British navy to enforce it’s tough sounding doctrine.

… the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for colonization by any European powers.

Ostensibly, this applied to the British as well as the Holy Alliance powers, but the United States really lacked the power to make it stick. That is where appeals to mutual self interest with the British allowed the United States to benefit from the might of the British Empire, while at the same time, appearing a bit arrogant! Ironically, all the work to craft the famous doctrine occurred after the threat of European intervention had already passed. In 1824, Monroe, in his final Congressional address, claimed that the Holy Allies “appeared to acquiesce” to the demands of the United States as a result of his rhetoric! Although this was clearly not the case, it made for great propaganda. What the Monroe Doctrine did do, however, was to provide definition to what would become a nearly century-long struggle between Britain and the U.S. for dominance in the hemisphere. Sexton points out one of the key factors in the success of the speech:

The Monroe administration framed the message in negative terms: they stated what European powers could not do, but dodged the questions of what the United States would do.

Monroe’s administration never answered this question, neither did it address the issue of U.S. territorial expansion. It clearly wanted to keep open the possibility of acquiring Texas and Cuba. They calculated that such expansion would happen as a result of “self-determination.” The peoples in those territories would voluntarily choose to enter the union.

Subsequent interpretations of the doctrine would dance around territorial expansion in different ways and for different reasons. As mentioned earlier, Southerners only supported expansion if slavery were promulgated and did not, if it wasn’t.   The situation in Mexico was a crucible in which the application of the Doctrine was tested. Although Henry Clay and Daniel Webster both sought congressional sanction for a more active foreign policy, neither succeeded.  Many in Congress questioned the Constitutionality of an expansionist interpretation – e.g. it might give a “blank check” to the executive branch. Others objected on the grounds of the dangers George Washington warned of — foreign entanglements. But, behind the scenes a group of Southern Congressman, led by John Randolph, objected to expansionism because they thought it would increase the powers of the central government. They worried that one day a strong central government would turn against the institution of slavery. In particular they were concerned lest Haiti be recognized as a republic comprised of free blacks.

Subsequent interpretations of the doctrine would dance around territorial expansion in different ways and for different reasons. As mentioned earlier, Southerners only supported expansion if slavery were promulgated and did not, if it wasn’t.   The situation in Mexico was a crucible in which the application of the Doctrine was tested. Although Henry Clay and Daniel Webster both sought congressional sanction for a more active foreign policy, neither succeeded.  Many in Congress questioned the Constitutionality of an expansionist interpretation – e.g. it might give a “blank check” to the executive branch. Others objected on the grounds of the dangers George Washington warned of — foreign entanglements. But, behind the scenes a group of Southern Congressman, led by John Randolph, objected to expansionism because they thought it would increase the powers of the central government. They worried that one day a strong central government would turn against the institution of slavery. In particular they were concerned lest Haiti be recognized as a republic comprised of free blacks.

But it wasn’t just Haiti which occupied the minds of successive U.S. politicians. Cuba also remained a constant source of agitation as far back as Monroe’s time. Newly elected President John Quincy Adams refused a British proposal that the British, French and Americans sign a pact not to take the island in the future. However, neither did he or his Secretary of State, Henry Clay, want to annex the island. That would have provoked the powerful British. Clay was also motivated by the thought that

… the destabilization of slavery in Cuba would threaten the Union by inspiring slave revolts and by leading Southerners to demand controversial safeguards to protect their peculiar institution.

The solution was to perpetuate Spanish rule of the island.

First, Adams and Clay believed Cuba to be of such strategic importance that they decided against any change to what was an acceptable status quo. Second, the administration viewed the affair in relation to internal affairs. Domestic political considerations ruled out annexation, which would reopen the divisions from the Missouri crisis.

Ten years later, Andrew Jackson demonstrated how the Doctrine could be selectively enforced, or rather ignored, when the British seized the Falkland Islands from Argentina. In spite of his distaste for the British, Jackson figured it was better for the U.S. to have the Falklands under British control, than in the hands of Buenos Aires, which had been denying American fishing and sealing rights.

Closer to home, the famous Doctrine also figured into the annexation of Texas. Because of concerns over the extension or abolition of slavery, the U.S. was reticent to annex Texas. As Sexton puts it,

Closer to home, the famous Doctrine also figured into the annexation of Texas. Because of concerns over the extension or abolition of slavery, the U.S. was reticent to annex Texas. As Sexton puts it,

Calhoun sought to contain the cancer of abolition. he concluded that the South could not allow the contagion to spread to the remaining strongholds of slavery in North America: Cuba and Texas.

When Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836, Jackson would only have been too happy to extend recognition to his buddy Sam Houston, but worried that outright annexation would provoke Mexico and also stir up domestic political conflict. Once again, the Monroe Doctrine was used as a cover for resolving domestic political issues. Houston began flirting with the British who were abolitionist in policy and alarmed the Southern politicians. British statesman openly advocated for an independent, anti-slavery Texas. Meanwhile, abolitionist societies in Britain were helping to mobilize and fund the abolitionist movement in the United States.

Under a pro-slavery interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1844-45, the United States made its move toward annexation.  Pro-slavery statesmen determined that the annexation of Texas was the only way to keep the British from turning the tide in Texas away from slavery.

They argued that the circumstances demanded preemptive action on the grounds of national security. A proslavery reading of Monroe’s 1823 message provided the appearance of precedent for such a course: after all, they argued, the Monroe administration clearly had its eye on Texas …

These mental gyrations enabled Calhoun to kill two birds with one stone, to protect against the external anti-slavery threat from Britain and to smooth over the internal politics of the Union.  Ironically, this didn’t go over too well with John Quincy Adams who wrote in his diary that the annexation of Texas treated the Constitution “like a menstruous rag.”

These mental gyrations enabled Calhoun to kill two birds with one stone, to protect against the external anti-slavery threat from Britain and to smooth over the internal politics of the Union.  Ironically, this didn’t go over too well with John Quincy Adams who wrote in his diary that the annexation of Texas treated the Constitution “like a menstruous rag.”

The proslavery and constitutionally questionable dimensions of annexation led Adams to completely reverse the position he took on Texas in the cabinet debates of 1823 when he had held out hope for future annexation of the territory (as well as Cuba.) Adams became so despondent about the increasingly proslavery slant of his beloved union that he came too see Britain as the last hope for maintaining freedom in the new world. “The freedom of this country and all of mankind,” Adams privately confessed, “depend upon the direct, formal, open and avowed interference of Great Britain to accomplish the abolition of slavery in Texas.” In this remarkable passage, the statesman most important to the formulation of the message of 1823, the statesman who had passionately argued against accepting Canning’s [British diplomat of Monroe’s era] offer, now called for his nation’s greatest rival to intervene in a territory he had long coveted.

Calhoun and others were not consistently advocates for expansion. They opposed intervention in Mexico because slavery had not yet taken root there and they did not want to provide a foothold for antislavery forces. Once again the Doctrine was interpreted as best fit the political need of the time. In the administration of James Polk, Calhoun argued that the Doctrine he’d used so well in his arguments to annex Texas was specific to the circumstances of 1823 and never intended as a “binding” doctrine for subsequent administrations. Calhoun and his cohorts interpreted the Monroe Doctrine as designed “to protect the interests of Southern slaveholders by containing the spread of emancipation in places of strategic importance in the new world.” Hence, as long as Spain managed to keep Cuba and didn’t flirt with freeing its slaves, they were content to let Spain keep it.  If not, the United States would need to take preemptive action under the guise of the Monroe Doctrine.

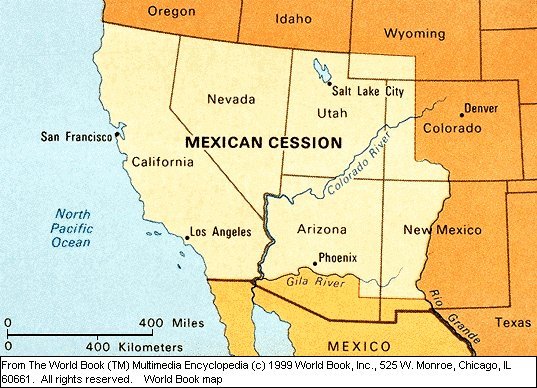

Polk had his own agenda, that of expansion. He transformed the Monroe Doctrine into a “proactive call for territorial expansion.” Again it was used simultaneously to send a message to the statesmen of the “Old World” and also to disarm political opponents at home. Under Polk, expansion was justified by the sense of entitlement that America had a right to expand within her natural confines — Manifest Destiny.

Polk exploited fears of foreign intervention in order to build up support for active policies in the future, but he did not publicly commit himself to any particular diplomatic approach…

Polk’s aim was to consume as much of Mexico as he could. All rhetoric aside, he didn’t really care too much about the rest of Latin America. Even when the British and French intervened in a dispute between Argentina and Uruguay in 1845, Polk chose to look the other way.  In 1845 Texas was annexed to the United States precipitating war with Mexico in which the United States was victorious. With the ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 – Polk acquired California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of New Mexico and Colorado.

After the distraction of the American Civil War, the Doctrine again took center stage in American foreign policy, albeit in a new way. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish (under Ulysses S. Grant) sought to project U.S. influence through peaceful means, by establishing protectorates, new markets, and negotiating advantageous trade agreements. Influenced by the British Gladstone, he aimed to bring the United States into the “club” of “great European powers.”

Sexton traces the beginnings of the political maneuvering surrounding the construction of a Central American canal. Fish didn’t give a fig for the independence of Nicaraguans, and didn’t bother to include them in negotiations over canal policy with European powers. Neither did he care about Cuba which became the central foreign policy issue of Grant’s presidency, for both terms. There was a lot of pressure to finally annex Cuba and fulfill the prophecy predicted by Jefferson and John Quincy Adams – that it would ultimately fall into American hands. Frederick Douglas was among the supporters of such a policy – in keeping with yet another interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine.  This was a call to intervention in the Ten Year’s War (Cuba’s war for independence) and finally kick the Spanish out of the Western Hemisphere in keeping with the United States’ new antislavery crusade.

However, Fish, who reminds this reader a great deal of Woodrow Wilson, opposed annexation or intervention of an island populated, in his view,  by racial inferiors. Sexton quotes from Fish’s diary for his views on the Cubans as “of a different race and language, unaccustomed to our institutions or self government: we would not wish to incorporate them with us.”

In spite of the multiplicity of interpretations and uses to which the Doctrine was put,  recurring themes appear under almost every presidency from its inception under Monroe and John Quincy Adams through Teddy Roosevelt. Some of these themes are:

- Its use as a diplomatic bulwark against European interference in America – when it suited immediate needs

- Its use as a tool to provide domestic political cover for or against slavery and/or abolition

- Justification for action or inaction in Cuba, Haiti, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic

- Its use as a principle for justifying or opposing expansionism

There is a lot more in this book than can be adequately covered in scope of this review. There are several chapters on how Teddy Roosevelt transformed the Monroe Doctrine into an instrument of interventionism – again justifying the actions based on the primacy of the United States and a certain elitist view of its obligations. “It is our duty to police these countries in the interest of order and civilization.” In reading the last portion of the book, this reader was reminded of another book titled The Imperial Cruise. Unlike Bradley, Sexton doesn’t seem to have an ax to grind. He doesn’t sugar coat any uncomfortable facts, but he allows the reader to make his own judgments and provides the context in which to do so.

There is a lot more in this book than can be adequately covered in scope of this review. There are several chapters on how Teddy Roosevelt transformed the Monroe Doctrine into an instrument of interventionism – again justifying the actions based on the primacy of the United States and a certain elitist view of its obligations. “It is our duty to police these countries in the interest of order and civilization.” In reading the last portion of the book, this reader was reminded of another book titled The Imperial Cruise. Unlike Bradley, Sexton doesn’t seem to have an ax to grind. He doesn’t sugar coat any uncomfortable facts, but he allows the reader to make his own judgments and provides the context in which to do so.

The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth Century America, provides a great deal to think about. Though its author does an admirable job of maintaining an objective tone, it does leave the reader wondering what might have been if the Doctrine had been interpreted consistently in one direction or another and not been subject to the vagaries of domestic tension over slavery. For instance, would Cuba be better off today if, whatever the justification, the United States had annexed it?

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment