Adams and Jefferson – an Interesting Dichotomy

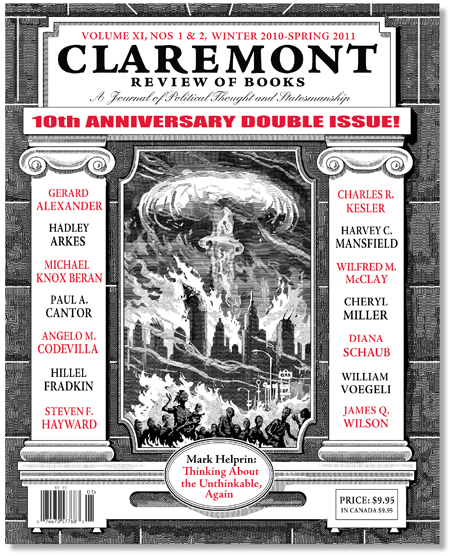

The most recent double issue of the Claremont Review of Books contains an interesting essay by Richard Samuelson entitled Jefferson, Adams, and the American Future. It is adapted from a lecture by the author about these two unlikely friends. Samuelson points out that both men deserve the appellation of Founding Father, and to be considered as republicans with a small ‘r.’ And, there were other similarities as well, such as their participation in the formulation of their respective State governments. Adams drafted the Constitution for Massachusetts in 1779 and it was the first to be written and adopted by special convention and ratified by the people. Jefferson contributed his own constitution to Virginia, and while it was not accepted, many of his reforms were.

The most recent double issue of the Claremont Review of Books contains an interesting essay by Richard Samuelson entitled Jefferson, Adams, and the American Future. It is adapted from a lecture by the author about these two unlikely friends. Samuelson points out that both men deserve the appellation of Founding Father, and to be considered as republicans with a small ‘r.’ And, there were other similarities as well, such as their participation in the formulation of their respective State governments. Adams drafted the Constitution for Massachusetts in 1779 and it was the first to be written and adopted by special convention and ratified by the people. Jefferson contributed his own constitution to Virginia, and while it was not accepted, many of his reforms were.

However, it is their differences that make their friendship interesting. Samuelson points out, “At the root of the disagreement was a classic philosophical or even theological question: what is the cause of evil in the world?”

Adams believed that, regardless of “enlightenment” and science, man was fundamentally an imperfect creature, subject to the same foibles as every generation that had gone before. Science was just another tool at the disposal of those in power, the same as wealth and family name had been from time immemorial.  Jefferson believed that science acted as a great equalizer. No longer would physical attainments be sufficient for those who possessed them to dominate their fellows. In his mind, this gave power even to the physical weakling. Jefferson, like Paine thought they could now “begin the world anew.” He, like later Progressives, saw the evolution of man as one of perpetual improvement, culminating in a Utopian vision. Adams didn’t see things that way, “… I must esteem all the speculations of divines and philosophers about universal and perpetual peace as shortsighted, frivolous romances.”

Similarly, they had different views on the meaning of history.

Adams and Jefferson both employed the modern scientific method, but not in the same way. Jefferson selected facts from history to describe change over time, from a lower to a higher plane of existence. Adams, by contrast, was inclined to study the behavior of human beings in the same way modern scientists study the behavior of, say, ants. Rather than doing controlled experiments, however, his data set was historical. Drawing upon that data he discovered patterns. Wherever one found humans, one found certain things—governments, religion, families, private property, etc. From that data, one discovered general rules. These described human nature.

Samuelson also contrasts the two men’s beliefs on the role of religion and their respective interpretations of the French Revolution. It is a fascinating essay that shows how the crux of their arguments continues even today.  For example, the system of checks and balances in the new government that they each took a turn presiding over, Adam’s skepticism served to balance Jefferson’s optimism. Samuelson puts it this way:

Progress was and remains difficult, but, thanks to Jefferson, it is enshrined as a goal of the American regime, even if, thanks to Adams, it is a chastened, and one hopes chastening, goal.

Adams chastening is not much evident today, while Jefferson’s vision appears to be in ascendency. As Thomas Sowell explains in his book, The Vision of the Anointed, “The rise of the mass media, mass politics, and massive government means that the beliefs which drive a relatively small group of articulate people have great leverage in determining the course taken by a whole society.”

Sowell goes on to explain the corollary to that leverage is that the assumptions underlying  the prevailing vision are rarely questioned. Empirical evidence is ignored or denied as not merely being wrong, but as being immoral. Critics are demonized as racist, uncaring, irresponsible, or worse.

The deleterious results of the welfare state, the scientific weaknesses of global warming, the disasters of central planning, Â have all been amply demonstrated, but have not caused the articulate elites to waver.

The danger of the  Jeffersonian vision, of course, is that if man is capable of perfection,  all that is needed is for the smartest among us to find ways to perfect him. The point being that such a vision knows no bounds. It is antithetical to liberty. It always results in the application of force, whether through government fiat, or worse.

John Adams said it best. Â “It is weakness rather than wickedness which renders man unfit to be trusted with unlimited power.”

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

And to think Jefferson thought man was improving, heading for utopia. Since there has been Mao, Stalin, Hitler, Castro and Pot just to name a few. Look at America. It’s not getting better. And, it’s not getting better, because its people aren’t getting better. They are voluntarily letting this government corrupt and destroy them. To any others, who think as Jefferson did, history has proven otherwise. We are currently proving otherwise.

[Reply]

[…] What Would The Founders Think? – Adams and Jefferson – an Interesting Dichotomy […]

Leave a Comment