Admiral Byng His Rise and Execution by Chris Ware

If you’re an aficionado of British naval history, a Patrick O’Brian fan, or both, you shouldn’t pass up this book by historian Chris Ware. Ware meticulously researched the life and times of his unfortunate subject, Admiral John Byng.

If you’re an aficionado of British naval history, a Patrick O’Brian fan, or both, you shouldn’t pass up this book by historian Chris Ware. Ware meticulously researched the life and times of his unfortunate subject, Admiral John Byng.

Byng followed in the footsteps of his father, George Byng who distinguished himself with a successful career in His Majesty’s Royal Navy as a captain, admiral and on the Board of the Admiralty. The latter position did not preclude him from going to sea. His last ventures were among his most profitable.   It was during these that he brought his son John into the service and began exercising his “interest” on his behalf.

By all accounts, John Byng was a capable, if uninspiring officer. Notwithstanding his father’s influence, his rise through the ranks could not be described as meteoric.  Still, he was a moderately successful captain and ultimately his turn came to “raise his flag.” O’Brian fans will recognize the term used to denote promotion to admiral. Once an officer was “made post” (promoted to the rank of Post Captain) , he merely had to live long enough before seniority ensured his ascendance to admiral. O’Brian’s Captain Aubrey was forever checking his position on “the list.” Still, in Byng’s time and later, while influence and position certainly played a significant role in which officers were promoted to the coveted rank of Post Captain, a certain level of competency and accomplishment was required. This is to say John Byng was a decent officer and probably deserving of his captaincy.

However, merit played little if any role in the next stage of an officer’s career. As indicated above, seniority and vacant positions were the sole determining factors as to who would “raise his flag.” An Admiral or Commodore (temporary rank given to a senior captain over several vessels) was a vastly different job than commanding a single ship. In such a position, there was often an intersection of politics as well as tactics and strategy which had to be employed. This was especially true when conducting joint operations with the army. Unfortunately for Byng, he sailed straight into the perfect storm created by lackluster politicians and the vagaries of war.

Byng preceded the famous Admiral Nelson by about half a century. What this meant in practical terms is that the Royal Navy had yet to devise a sophisticated signaling system. Instead they relied on a predefined set of very restrictive maneuvers, minutely described in the official Sailing and Fighting Instructions. These instructions, coupled with the difficulties in signaling made it very difficult to control a long string of ships. Smaller ships, known as frigates, were often used to ply up and down the line and relay instructions.

Setting the Stage

In early 1754 the British and French had commenced hostilities in America with what we call the French and Indian War. Things weren’t going well for Great Britain. Ever fearful of an invasion closer to home, the government wanted to bolster its strength in the Mediterranean Sea and English Channel. The British were also concerned that their Spanish allies might succumb to French influence. The British held Gibraltar and the island of Minorca, a place of strategic importance. They anticipated that the French fleet at Toulon was destined for an attack on Port Mahon. To forestall this, they sent an undermanned fleet under the command of Vice Admiral John Byng, along with a quantity of army troops and officers to bolster Fort St. Philip (at Port Mahon).

Byng’s Fleet Action

Byng tried unsuccessfully to communicate with forces at St. Phillip. The octogenarian acting governor insisted on a daily counsel of war – at noon, presumably after he got up. And so he refused to meet the small boat sent in to discuss plans with the garrison. In fact, they fired on it, confused as to its identity.   Meanwhile, the French fleet arrived. Byng sailed out to meet them in the offing, eventually gaining the ever desired “weather gage.” That was the last of Byng’s good fortune.

Attacking the French fleet at angle, a majority of his fleet, including his flagship was unable to engage the French. In the confusion and the smoke, signals were unheeded and some ships, in an attempt to adhere to the then sacrosanct Sailing and Fighting Instructions, actually slowed their progress so as not to overtake the vessel they were assigned to follow. Consequently, the French fleet concentrated their attacks against only a few of Byng’s ships, inflicting heavy damage while remaining largely unscathed. At one point someone suggested to Byng that he deviate from the Sailing Instructions so as to bring more of his fleet into the fight. Byng declined, citing an earlier case where an officer had been dismissed for doing this.

When the French broke off the fight, their forces intact, Byng held a counsel of war amongst his captains and the army officers who had been destined to relieve the fort at Minorca. Byng allowed himself to be convinced that it would be pointless to attempt a rescue of the port, or to battle the French again, given the state of his ships. Instead after four days of sailing near Minorca, he decided it would be more prudent to return to Gibraltar to refit and ensure the safety of that port.

Politics at Play

Bad news travels fast. The French were eager to publicize their victory over the vaunted British navy. Byng reached Gibraltar, offloaded his wounded and awaited reinforcements to take back for the relief of Minorca. However, before he was able to disembark, a ship arrived from England with orders to relieve him of his command and escort him back to England.

Back in England, he was placed into custody to await court martial. Byng was completely unprepared for the situation that awaited him on his return. Unbeknownst to him rival factions in government were fighting amongst themselves seeking to pin blame for the loss of this important naval outpost. Byng ended up being the scapegoat and the victim of a virulent campaign waged in the press in which he was depicted as a coward, if not an outright agent of the French. Much of this press was orchestrated by the government, and Byng was unable to counter it since he was en route for much of the time it was conducted.

One of the more grotesque disservices that the politicians did to Byng in his absence was to publish a heavily redacted version of a dispatch he sent to the admiralty. Through careful editing they made it seem as though Byng was proud of running away. Later his proponents published the complete dispatch, but by then the damage was done and Byng was despised by a populace whipped into a furor by the politicians orchestrating the campaign to shift blame on Byng.

Ware does not claim that Byng made all the right decisions, merely that Byng was not dishonorable in his actions. However, being honorable was not enough, and his failures made him a convenient scapegoat for the failures that the government had already suffered elsewhere (Braddock’s march), as well as for the loss of Port Mahon.

In the time between Byng’s return to England and his court martial, the government underwent a transition in power. However, this did not mean that those out of power did not still wield influence, or were any less eager to shift the blame for the catastrophe.

Ultimately, Byng was not convicted for cowardice or disaffection, but because he had “failed to do his utmost” to defeat the enemy and prevent the capture of Minorca, the court had no discretion about the punishment required. Under the “Articles of War,” as any O’Brian fan can quote, the guilty party “shall suffer death.” Article 12:

Every Person in the Fleet, who through Cowardice, Negligence or Disaffection, shall in time of Action withdraw or keep back, or not come into the Fight or Engagement, or shall not do his utmost to take or destroy every Ship which it shall be his Duty to engage, and to assist and relieve all and every of His Majesty’s Ships or those of his Allies, which it shall be his Duty to assist and relieve, every such Person so offending, and being convicted thereof by the sentence of a Court Martial, shall suffer Death.

and 13:

Every Person in the fleet, who though Cowardice, Negligence or Disaffection, shall forbear to pursue the Chace of any Enemy, Pirate or Rebel, beaten or flying; or shall not relieve or assist a known Friend in view to the utmost of his Power; being convicted of any such Offense by the Sentence of a Court Martial, shall suffer Death.

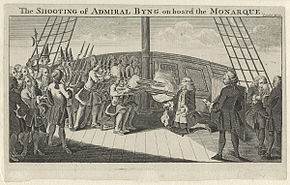

And so, after a few unsuccessful attempts to forestall his execution with pleas for leniency (some of which probably did more harm than good), Byng was executed by a firing squad on HMS Monarch in Portsmouth harbor.

Ware examines the evidence, the trial and surviving documentation and concludes:

What can be said with certainty is that John Byng was an honourable man in every sense of that word, and both in his life and the manner of his death he bore testament to that fact.

Byng’s epitaph is a sobering reminder of the unseemly nature of politics

To the perpetual Disgrace

of PUBLICK JUSTICE

The Honble. JOHN BYNG Esqr

Admiral of the Blue

Fell a MARTYR to

POLITICAL PERSECUTION

March 14th in the year 1757 when

BRAVERY and LOYALTY

were Insufficient Securities

For the

Life and Honour

of a

NAVAL OFFICER

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment