Artful Apologists

“The first and governing maxim in the interpretation of a statute is to discover the meaning of those who made it.†James Wilson, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, in Of the Study of Law in the United States

On July 6, 2005, the New York Times published an op-ed piece titled, “So Who Are the Activists,†by Paul Gewirtz and Chad Golder. The intent of the editorial was to turn the table on conservatives who used activist as a pejorative term. They started by claiming that there was no definition for so-called activist rulings—except that the person using the term was simply disagreeing with a decision. This left the field wide open for them to invent their own definition. Gewirtz and Golder based their definition on how many times a justice voted to strike down a law passed by Congress. The premise was that judges that overruled democratically enacted laws were the true activist.

With this definition in hand, Gewirtz and Golder ran some numbers and reversed the generally perceived order of activist sitting justices, with Clarence Thomas now being tagged as the supreme activist, and Stephen Breyer celebrated as a paragon of judicial restraint.

Did this analysis make sense? First, there was already a generally accepted definition of an activist judge. The term was used for justices who venture into the legislative or executive realm. But this was not the biggest problem with this New York Times opinion piece. The fatal error was that the premise was wrong.

Gewirtz and Golder opened by writing “Congress, as an elected legislative body representing the entire nation, makes decisions that can be presumed to possess a high degree of democratic legitimacy,†and conclude their editorial by claiming that their analysis “clearly illustrates the varying degrees to which justices would actually intervene in the democratic work of Congress.†Everything the authors’ conclude is derived from this premise—the Supreme Court has no right to overrule democratically enacted laws.

The philosophical dispute might be hard to follow, but fortunately, Paul Gewirtz provides us a practical example. In another New York Times op-ed piece published almost exactly five years later, on July 2nd, 2010, Gewirtz writes, “It is no secret that the current Supreme Court is an activist one in striking down congressional legislation — just look at the prominent cases from the court’s just-completed term, most notably Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, in which a 5-4 majority of the court’s more conservative justices struck down key provisions of Congress’s bipartisan campaign finance laws.†In this editorial, Gewirtz ups the ante by bolstering unassailable democratically enacted laws with the ever-alluring bipartisan stamp of approval.

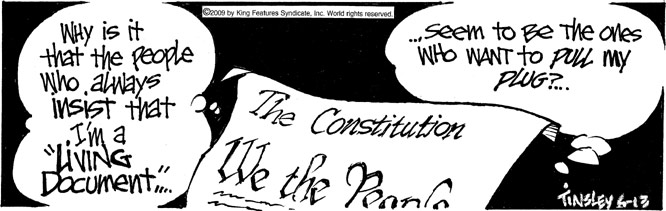

The Supreme Court’s job is to evaluate laws based upon their constitutionality, not the popular will. The United States is not a democracy. It is a republic. All three branches are supposed to operate under the auspices of the Constitution. If the judiciary felt obligated to rubber stamp every law passed by Congress, then we have no need for a Constitution.

Thomas Jefferson Writes a Letter

Gewirtz and Golder are pretty smart guys, but I don’t think they are in the same league with Thomas Jefferson. At a White House dinner, John F. Kennedy said, “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.†In 1819, Jefferson forewarned a friend against treating the Constitution like, “a mere thing of wax.†Here is an abridged version of the letter.

If this opinion be sound, then indeed is our constitution a complete felo de se. (Felo de se is an archaic term for suicide.) For intending to establish three departments, co-ordinate and independent, that they might check and balance one another, it has given, according to this opinion, to one of them alone, the right to prescribe rules for the government of the others, and to that one too, which is unelected by, and independent of the nation. For experience has already shown that the impeachment it has provided is not even a scarecrow; that such opinions as the one you combat, sent cautiously out, as you observe also, by detachment, not belonging to the case often, but sought for out of it, as if to rally the public opinion beforehand to their views, and to indicate the line they are to walk in, have been so quietly passed over as never to have excited animadversion (criticism), even in a speech of any one of the body entrusted with impeachment. The constitution, on this hypothesis, is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist, and shape into any form they please.

How do we reverse this inclination to treat the Constitution as a living document? Unfortunately, the justices read the New York Times and confuse it with popular sentiment. They shouldn’t rule based on what’s popular, but since they do, we the people must collectively raise our voices to drown out the New York Times and all the other self-important busybodies. If we speak loud and often enough, our voices will eventually penetrate the marble facade of the Supreme Court Building.

James D. Best is the author of Tempest at Dawn, a novel about the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment