Bloody Spring Forty Days That Sealed the Confederacy’s Fate By Joseph Wheelan

Bloody Spring

Bloody Spring

Forty Days That Sealed the Confederacy’s Fate

By Joseph Wheelan

A visit to a bookstore or Amazon.com reveals a great many books about the American Civil War. So why did Joseph Wheelan write another? He explains in the prologue to Bloody Spring:

Because the battles followed one another so closely, the battlegrounds – at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, and Cold Harbor – would not live as deeply in the collective memory as had Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Chancellorsville, Shiloh, Fredericksburg, Manassas, and Antietam. Soaked in blood, core, and horror though they were, the battlefields of Grant’s Overland Campaign would remain relatively unknown.

Bloody Spring is a detailed account of those battles and the men who fought them. The author’s narrative is so compelling that readers may find it difficult to dislodge Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse and Cold Harbor from their collective memories.

Spring 1864 marked the fourth campaign of a conflict that still seemed far from resolution. The North was tired of the war, sick of its cost and despairing of the growing number of its dead sons. Initial optimism for a quick victory had long given way to impatience and resentment. Lincoln’s popularity was waning along with support for the war. Unless the Union Army could demonstrate success against the Confederacy, he would not be re-elected. His replacement, given the prevailing mood, would likely negotiate a peace that would permit the Confederacy “to coexist as a sovereign nation beside the Union-a situation that Lincoln, if reelected, could never tolerate.â€

Lincoln was fed up with careerist and risk-averse Union generals unable, or unwilling to use the North’s advantages of men and materiel to engage the enemy, or to pursue him on the rare occasions the Union held the field.

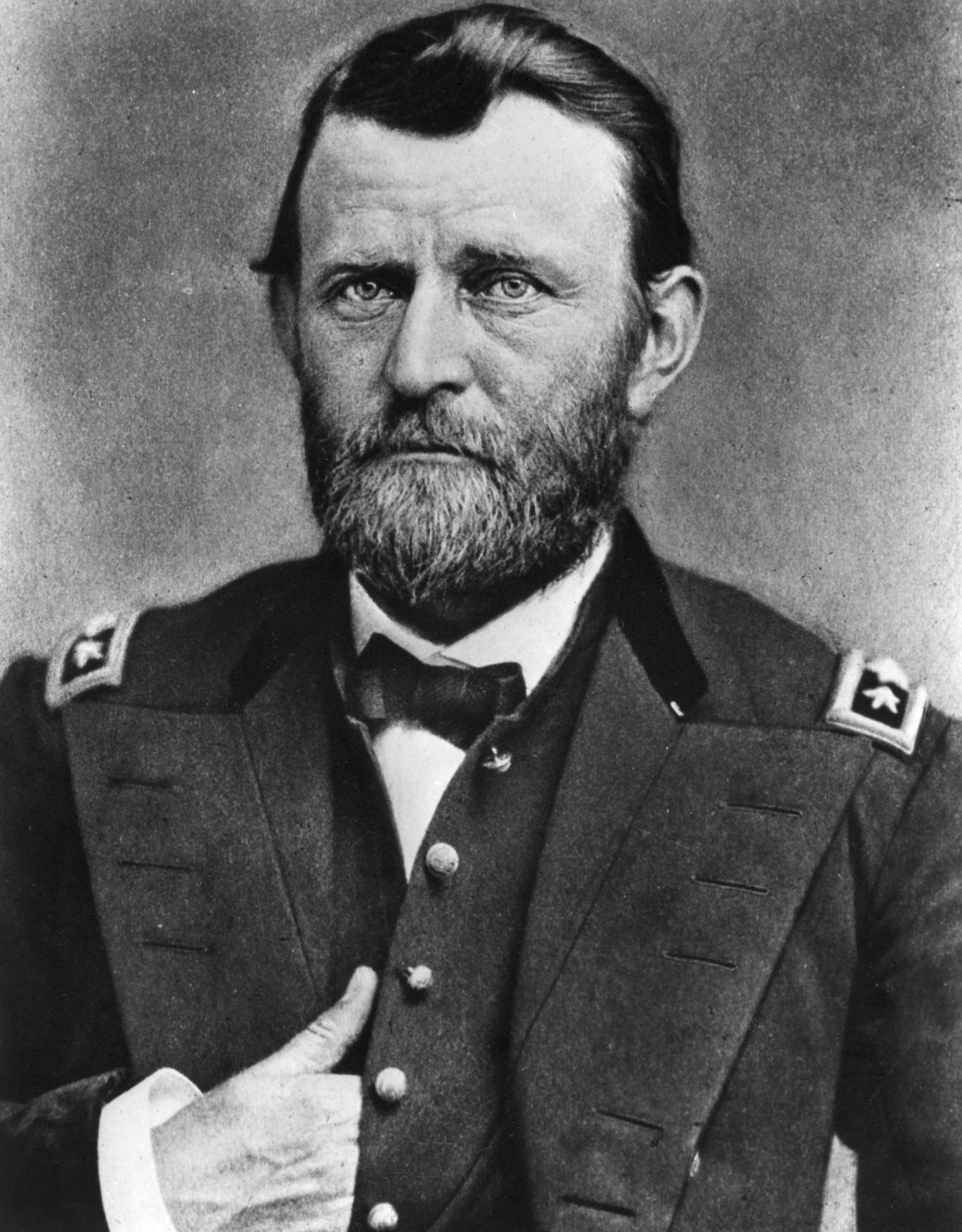

The president’s desperate search for an aggressive commander ended with his appointment of Ulysses Grant in March of 1864. Grant had won more battles than any other Union general. His record in the West so impressed Lincoln that he gave Grant sweeping powers. He would command 533,000 men, one of the largest armies in history. Grant, cognizant of the political ramifications of failure, promised Lincoln he would defeat Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, take Richmond and end the War.

The Union campaign conflated daunting military and political stakes. Grant’s destruction of Lee’s army would assure the survival of Abraham Lincoln’s administration and the defeat of the Confederacy; conversely, Lee’s triumph would sink the Lincoln administration and all but guarantee the Confederacies survival.

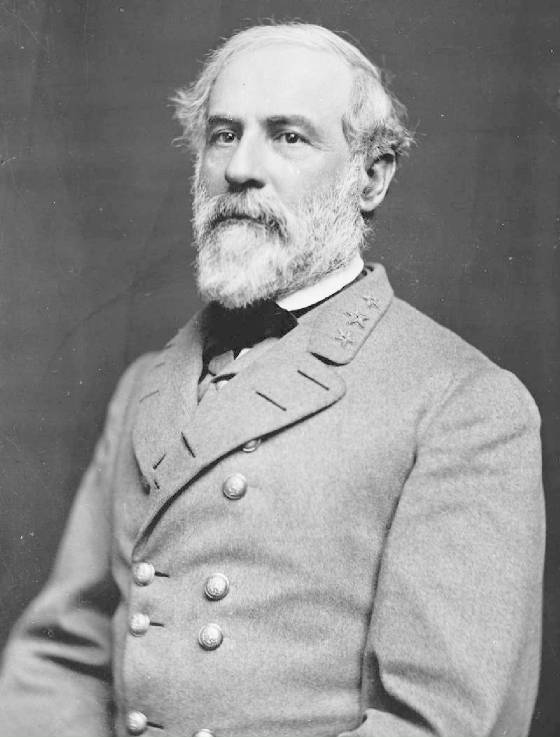

A hundred thousand well-armed, well-fed Union soldiers, miles of supply trains and artillery batteries converged on Northern Virginia. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, consisting of roughly 64,000 poorly clothed and provisioned troops, was waiting for them.

Grant ’s plan for the Overland Campaign was to use the North’s superior manpower and industrial might to grind the Confederacy down. He would attack everywhere at once and at the same time destroy the railroads that provisioned the Rebels, their lines of communication and strip the countryside that provided them with food and forage. But Grant’s primary target was always the Army of Northern Virginia.

All Grant’s advantages not withstanding, he had problems to overcome. The Army of the Potomac had a surfeit of “political†generals lacking military experience and officers who secretly feared that Lee was invincible. Four generals had failed to win a single battle against the Army of Northern Virginia in two years. Officers were overly cautious, slow to react to changing conditions and the Army of the Potomac was slower yet to move when ordered to do so.

Northern Virginia was unfamiliar territory to Grant but home ground for Lee whom Grant had never confronted in battle. Lee had a knack for anticipating his adversaries’ moves. He paid attention to details, studied terrain, and responded quickly to enemy vulnerabilities. Ragged and hungry as his army was, Lee had an advantage that did not lend itself to enumeration. The Confederates, led by the man they idolized, were fighting for their homes and way of life. The Bluecoats fought for an abstract ideal – the preservation of the Union.

The Southern strategy was to stay the course, attack when possible to further impress the North with the conflict’s futility, and bank on Northern war fatigue to force a compromise that would assure the Confederacy’s future.

Wheelan follows key officers in each army and examines their strengths and weaknesses. He obviously considers Lee tactically superior to Grant.

Grant and Lee would engage for the first time when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River. Grant’s plan was to skirt to the right of Lee’s position and locate between the Army of Northern Virginia and Richmond, the Confederate capitol, his ultimate goal.

The plan’s one, potentially daunting drawback was the Wilderness, where few fields and roads broke up the unyielding density of its thickets, woods and undergrowth. The Wilderness stood directly in the path of the Army of the Potomac.

It was a significant drawback.

A year ago nearly to the day, the Army of the Potomac had gone over the Rapidan at these very crossings– and three days later had come thundering back across after Stonewell Jackson flanked the army and General Joe Hooker lost his nerve. The Army of the Potomac had returned to try again with a new general.

But on the first day of the campaign, Grant’s army made a grave tactical error. It stopped while still within the boundaries of the Wilderness. The Rebels had “marched, bivouacked and fought†in the Wilderness and they knew it well. The Yankees were unfamiliar with area and their maps were inaccurate.

By stopping early on May 4, Grant and Meade granted Lee a glittering opportunity to strike at the massive Union army while it as still inside the claustrophobic Wilderness, a place that nullified Meade’s overwhelming advantages in numbers and artillery. ‘It was a region in which the power of discipline almost disappeared, in which the personal influence of commanders was at a minimum, in which tactics were literally impossible.’

Wheelan’s account of the three-day battle is so vivid that readers can almost smell the smoke from burning brush and hear the cries of the wounded trapped by the fast moving conflagration. The Union Army of 102,000 lost 17,666 killed, wounded or captured; the 64,000 Army of Northern Virginia’s lost 11,033.

Spotsylvania Courthouse was the second major battle of the Overland Campaign. Lee’s nimble Confederates had beaten the slow moving and poorly coordinated federals to the high ground presenting the Union Army with nearly impregnable fortifications. Almost 6,000 Union men fell in two assaults on Laurel Hill, the strongest point in the Confederate line. Confederate casualties were comparatively light at 600. But the worst was yet to come with some of the most brutal hand-to-hand fighting of the War.

Spotsylvania Courthouse was the second major battle of the Overland Campaign. Lee’s nimble Confederates had beaten the slow moving and poorly coordinated federals to the high ground presenting the Union Army with nearly impregnable fortifications. Almost 6,000 Union men fell in two assaults on Laurel Hill, the strongest point in the Confederate line. Confederate casualties were comparatively light at 600. But the worst was yet to come with some of the most brutal hand-to-hand fighting of the War.

The Yankees’ failure to break the Confederate line had many fathers, beginning with Grant and (General George) Meade. After drafting the initial attack plan Grant and Meade had left its implementation to subordinates.

The author argues: “Had they zealously monitored events from a forward command post where they could efficiently receive reports and send orders†they might have been able to rush in artillery to break up the Rebel counterattack and send in smaller units for reinforcement, avoiding the Union overcrowding that was so deadly.

However, assigning blame alone suggests that the Battle of the Bloody Angle was Grants to win, that his army, but for command failures, should have won a great victory. This one-sided analysis shortchanges the Rebel army and its commanders, particularly Robert E. Lee.

The battles continued and so did the stalemate.

Nine days after fording the Rapidan River, Grant’s army had advanced fifteen miles and fought more than half a dozen battles, neither decisively winning nor losing any of them. Of the 120,000 men that had begun the campaign, more than 36,000 were either in Army hospitals, on their way to Confederate prisons, or dead – about 30 percent of the army.

A Confederate soldier wrote:

We have met a man this time this time, who either does not know when he is whipped, or who cares not if he loses his whole army.

In fifteen days Grant’s army had suffered 37,000 casualties – more killed, wounded, and captured than in any campaign of the war.

Grant’s offensive against the entrenched Confederate army at Cold Harbor is distinguished by the pointless slaughter of Union soldiers in a campaign in which needless sacrifice was more often the rule than the exception.

Fifty thousand bluecoats from three infantry corps were poised to go into action against Rebel positions that had been cleverly concealed in the woods, hills and swamps. Seduced by the potential “momentous consequences†of a quick victory, Grant had chosen to forgo the careful preparation that might have identified weakness in the Confederate lines that could be exploited. Instead, he was blindly hoping to break through everywhere.

Confederate General Evander Law wrote of Cold Harbor: “It was not war; it was murder.â€

Unlike other generals Lee had fought, Grant had a stubborn determination that matched Lee’s own. High casualties did not deter him even when the objective was demonstrably unattainable. Grant consistently lost more men than the Confederates, but he had them to lose.

It appeared to this reader that the Union army’s numerical advantage caused Grant to be profligate with its use. Six days after the debacle at Cold Harbor the Union army again faced entrenched Confederates. This time before Petersburg where fumbling attacks against Rebel fortifications cost Grant another 11,000 casualties, nearly as many as his army had suffered at Cold Harbor.

The author’s artful interjections of excerpts from soldier diaries and letters home convey the tragedy of young lives cut short that recitations of casualty numbers do not.

In all, the Overland Campaign exacted a terrible toll of 66,000 Union soldiers killed, wounded or captured between May 5 and June 18.

Nothing like Grant’s ‘butcher bill’ had been experienced in this or any other war on the North American continent. It equaled two-thirds of the North’s casualties during the previous three years.

And all without tangible result; Lee’s army was battered but not destroyed and Grant had not taken Petersburg or Richmond.

But none of that mattered. While Grant fumbled at Petersburg the military situation changed. In the months before the election of 1864, the Federal Navy took Mobile Bay, General William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta and General Phil Sheridan secured the Shenandoah Valley. Lincoln’s reelection was secured and with it the last hope of the Confederacy was gone.

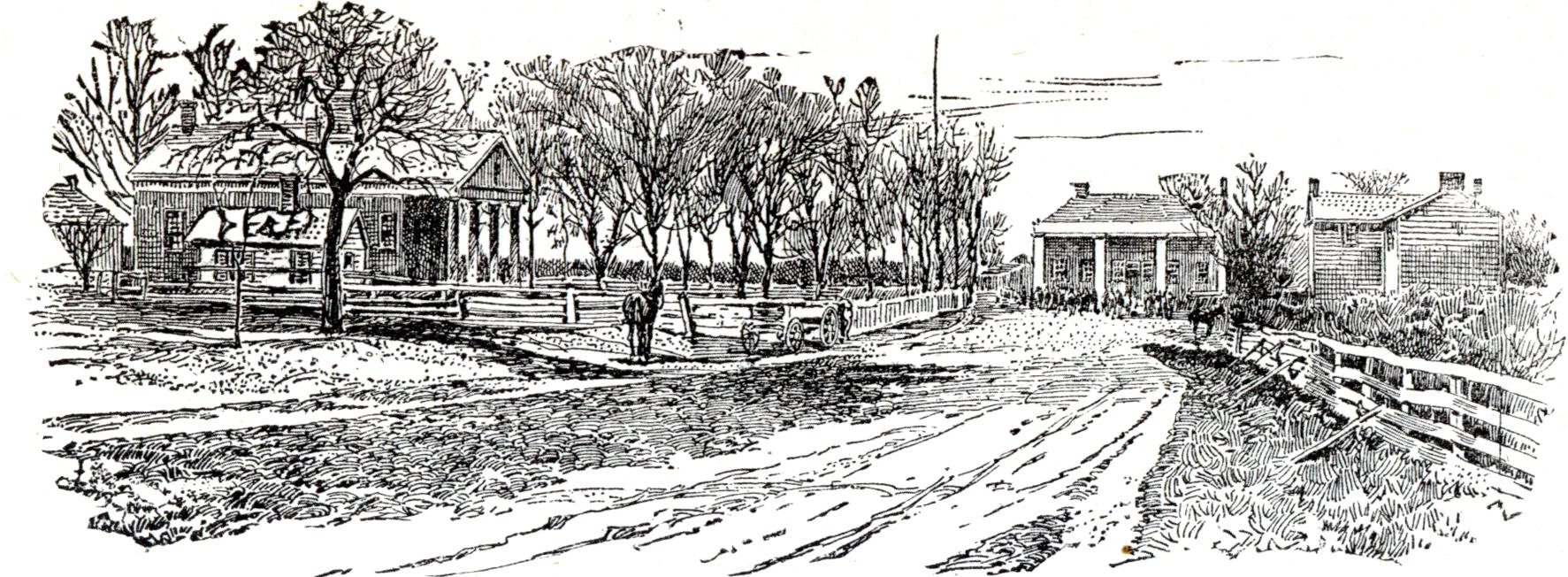

The 40 days of almost ceaseless battle had cost Lee his best generals and bravest soldiers and there were no replacements. Union forces took Petersburg on April 2nd 1865, Richmond on April 3rd. Lee surrendered a week later at Appomattox Court House.

Bloody Spring is a valuable addition to the Civil War compendium. One reviewer said that the book reads like a novel and that is correct. Except, of course, readers already know how this story ends. Bloody Spring is well written and engrossing. But it is not a book that can be read with equanimity.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment