Board Game Fun

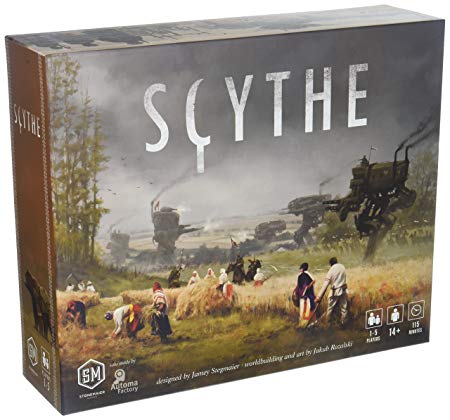

I took some time off for Christmas and devoted quite a lot of it to learning some new board games1. My wife and I took advantage of the fact that all 3 of our offspring were home for the Christmas break. One of the first games we cracked open was Scythe.

My son was intrigued with the look of this game and I had mused about a purchase as early as last summer. Then he went back to his university and I was reticent to lay out the $$ for it if he wasn’t going to be here to play. I waited … missed my opportunity on Prime Day and waited some more. Black Friday rolled around and I pulled the trigger and bought Scythe and Terra Mystica (but that might be for another post). In anticipation of his and his sister’s arrival in late December, my wife and I watched several video reviews and got a sense of what the game was about.

<ASIDE>

Watching video reviews of board games is great as far as it goes. Some reviewers are better than others. Some are clearly geared for the millennial generation, some are geared for neck-beards, some for geeks, and few for ordinary folk. Most have something of value to offer, some are boring, and some are annoying. One of the most useful reviewers I’ve found is Tom Vassel of Dice Tower. (He probably falls squarely into the geek camp.) Anyway, having watched numerous reviews, of many games, I have reached a conclusion: You really can’t tell what a game feels like until you play it. The reviews are useful, but they only go so far. They certainly help with learning a game and in getting a better view of the components and sense of the quality. Determining if you’ll like a game or not by how it feels to play is more subjective. For instance, I bought Terra Mystica without previously watching any reviews. (I confess, it was an impulse buy on Black Friday.) After the game arrived I watched a review and another play through video (that almost put me to sleep) and nearly returned the game unopened. After playing it the first time (with some trepidation), I found it to be very pleasant. I had the opposite experience with another game, Fort Sumter, which looked like it would be fantastic and turned out to be kind of dull. (This is, of course subjective as I had been hoping for a lighter version of Twilight Struggle.)

</ASIDE>

According to Wikipedia:

[Scythe is set] in an alternate history 1920s Europe, in Scythe players control factions which produce resources, build economic infrastructure, and use giant dieselpunk war machines called mechs to fight and control territory.[2]

…

In Scythe, players represent different factions in an alternate history 1920s Europe recovering from a great war, where each faction is seeking its fortune. Players build an economic engine by choosing one of four main actions each turn, listed on the top of their personal player board, which cannot be the same as the main action they selected in their previous turn. They can also take a corresponding second action listed on their player board. These actions allow them to move units on the board, trade for or produce goods, bolster their military, deploy mechs, enlist recruits for continuous bonuses, build structures, and upgrade their actions to make them stronger or cheaper.

Scythe is a really pretty game, the artwork is phenomenal on the game board as well as on all the various cards.

There are a lot of pieces in this game. In addition to the main board, which is a map, each player utilizes a player board and an upgrade board from which he will deploy his mechs (big war machines that sometimes look like something out of Star Wars on other times like tractors) and track his recruitment status. (Recruitment is one of several mechanisms the game uses to uncover capabilities.)

Actions may cost resources or money, or a combination thereof. Like Catan, different regions on the map produce different resources, and having workers in a region allows those resources to be gathered when a player does a “produce” action.

The player boards are unlike those in any other game I own. They allow the player to choose from a series of actions and make choices which affect the costs of future actions and the payoffs for them. Each set of player boards is different from the others. Certain aspects of these boards are shared but others are subtly different. The important thing to note is that despite the seeming complexity it’s fairly to straightforward to follow the instructions (pictograms) on each board. Thus, all one really has to know are a few simple concepts.

- Choose a an action – one of the four columns on the board – most of the boards prohibit the player from choosing the same action immediately after performing it.

- Decide whether to perform the top, the bottom or both components. It may not be possible to perform both in all cases.

For example, a player may choose the Move action and move one or more of his pieces on the (main/big game) board. He then may be able to perform the bottom action which varies board to board and requires resources to accomplish.

Scythe is thoughtfully designed, and a whole lot simpler to play than it looks. The game ends when any player accomplishes any 6 goals of the possible ten. The winner is the player with the most money at this point. Money is paid out based on a multiple of the accomplished goals and their “morale.”

Consequently, while combat is a part of the game, if not carefully planned, it can cost a player in terms of morale – and this can materially affect his end score.

There are a lot of strategies and things to try in this game. Each player has to manage resources, control territory, and accomplish goals, all while keeping his citizens’ morale high. There is not a lot of luck in Scythe and this was a major plus for my son.

This is probably as clear as mud. But that’s ok – just think like Nancy Pelosi – you gotta sign the bill to know what’s in it play the game to understand it. Fortunately, it’s a whole lot less convoluted (and expensive) than Obama Care.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment