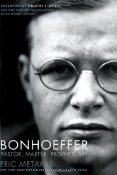

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy by Eric Metaxas

Author Eric Metaxas has written an unusual book. It is part biography, part history, and part philosophy. Ostensibly it is primarily the former more than the latter. However, it is much more than just the story of one remarkable man’s life. It is the story of choices and consequences. It is a depiction of brutal honesty and what it really means to stand for something.

Author Eric Metaxas has written an unusual book. It is part biography, part history, and part philosophy. Ostensibly it is primarily the former more than the latter. However, it is much more than just the story of one remarkable man’s life. It is the story of choices and consequences. It is a depiction of brutal honesty and what it really means to stand for something.

Bonhoeffer was a deeply religious man from an incredibly intellectual and refined family. The Bonhoeffer family exemplified class and dignity as members of Germany’s aristocracy. Thus Bonhoeffer’s choices are, at the same time, explicable in terms of his education and character, and incredible given his situation. Bonhoeffer could have kept silent, done nothing and survived the war. In fact, he also had the opportunity to escape his fate, and sit out the war in America. He did neither of these things, instead choosing to return to Germany, on the brink of the war, knowing that it was likely he would be imprisoned or worse.

So, who was this man Bonhoeffer, and why should we care? Unfortunately most people today have never heard his name and know nothing of him. This reviewer was among their number until someone passed him this book. Dietrich Bonhoeffer was part of a proud family with a rich heritage and place of distinction in German society. His father was a famous and much respected psychiatrist and his mother’s family had many connections with the Weimar government and military. (Many of these people were involved in plots to assassinate Hitler along with Dietrich Bonhoeffer.) It is a testament to Bonhoeffer’s father that, although he himself was a “man of science†and not religious, he could respect and discuss his son’s philosophical pursuits. When as a young man Bonhoeffer decided to study religion, his family, (other than his mother), may have thought it was a waste of his gifts, for Bonhoeffer was a brilliant intellect and talented musician. Nevertheless, initially it seemed that perhaps he was pursuing an interest in a philosophical, academic career, rather than in becoming a member of the clergy.

However, while much interested in the intellectual and philosophical side of religious studies, Bonhoeffer was equally, and ultimately more fascinated with the practical aspects of serving God. After making a name for himself with some brilliant doctoral and post-doctoral works, Bonhoeffer spent a year in Spain as an assistant pastor. He was too young to be ordained and too young to receive a position at the University. And he was torn between a career in academia and life in service to the church.

It was about this time that Bonhoeffer became involved in a major split within the German Lutheran church. Bonhoeffer argued on ecumenical basis for a real relationship with God, rather than for lukewarm Christianity. The “Confessing Church†in Germany came into being. Confessing did not mean confessional in the Catholic sense, but rather in the sense of bearing witness to the world as an evangelical movement. He saw how Hitler’s Reich was perverting and subverting Christianity for its own ends.

Thus, Bonhoeffer was on right side of history, but at cross purposes with Hitler’s Reich Bishop Müller.  Müller believed that any member who had Jewish ancestry should be expelled from the church. In 1936 the Reich Church was created. Its symbol was the swastika, not the Christian cross.

The Confessional Church, on the other hand, while opposed to Hitler’s plans, initially tried to go along and get along, for fear of persecution and loss of membership. Not everyone was as outspoken as Bonhoeffer. After all, many of Hitler’s activities were not well known by most people in Germany. While they may have thought him a little crazy, they saw that he was restoring national pride and getting Germany out from under the odious terms imposed upon them after the first world war. Hitler had made no bones about his plans for the Jews and his ideas for shaping German society in his screed, Mein Kampf. But, either people didn’t take him seriously, or simply didn’t realize the depths of his depravity. However, once the war began in earnest, Hitler dropped all pretense and began implementing his policies in earnest. He had consolidated his power to such an extent that there was no one who could challenge him openly.

Bonhoeffer and a few others in the “Confessing Church†did speak out. One of these was the head of the Confessing Church, Martin Niemoller. He was famous in Germany for his services as a U-boat captain in World War I. This made him an embarrassing and potent foe to the Nazis. In spite of his prominence, the Gestapo arrested him for opposing Hitler. He was sent to a concentration camp for 7 years and kept in solitary confinement. He was not alone in suffering this fate. Ultimately, Bonhoeffer was also arrested and executed on Hitler’s explicit orders, a mere 13 days before Hitler killed himself. Bonhoeffer was part of the failed plot to assassinate the Fuehrer.

Bonhoeffer and a few others in the “Confessing Church†did speak out. One of these was the head of the Confessing Church, Martin Niemoller. He was famous in Germany for his services as a U-boat captain in World War I. This made him an embarrassing and potent foe to the Nazis. In spite of his prominence, the Gestapo arrested him for opposing Hitler. He was sent to a concentration camp for 7 years and kept in solitary confinement. He was not alone in suffering this fate. Ultimately, Bonhoeffer was also arrested and executed on Hitler’s explicit orders, a mere 13 days before Hitler killed himself. Bonhoeffer was part of the failed plot to assassinate the Fuehrer.

So, how does a man of God justify being part of an assassination plot?  Hitler was as close to pure evil as anything that Germany had ever seen. Bonhoeffer recognized this and actively worked on at least two plots to kill Hitler with a bomb. He also tried to use his ecumenical contacts in other countries, in particular in England, to get assistance. Unfortunately once the war began, Churchill and others turned a deaf ear to those seeking to oust Hitler. Initially some of those involved in early plots against Hitler were trying to ensure that if they were successful, Germany would receive an amicable peace and transition to a new government. In the end, they realized that none of that mattered. Patriotism counted for little in the face of such overwhelming evil. Bonhoeffer never faltered in this belief.

In 1939, life was becoming very difficult for Bonhoeffer and some well intentioned friends in England and the United States arranged for him to take an academic position in New York. Against his inclinations, he agreed to sneak out of Germany. Amazingly enough, he made it to New York. However, no sooner had he arrived than he decided that he had made a mistake and given in to fear. He realized that his place was in Germany doing what he could to work against Hitler. He returned almost immediately, much to the dismay of those who had worked so hard to get him to safety.

It wasn’t safety that motivated Bonhoeffer, it was obedience to God’s will, regardless of the consequences. Bonhoeffer had done a lot of thinking about this and explained his view of the Christian life in his seminal book, The Cost of Discipleship.

Metaxas does not review this book in his own, but instead shows how Bonhoeffer exemplified what he wrote about, avoiding “cheap grace,†and instead opting for the hard road. In Bonhoeffer’s view, a man’s salvation is worth only the value that he himself puts upon it. It is either important or it isn’t. While he did not dispute the Lutheran view of being saved by grace rather than works, he argued for a deeper and personal relationship with God that would cause an honest Christian to value the gift of salvation by striving to follow God’s leading, whatever the cost to himself.

Cheap grace, on the other hand, is compartmentalized religion and leaves one without the basis to stand when things get tough. If you don’t value your faith, you will be less inclined to rely upon it when you need it most.

Bonhoeffer realized that many Christians in Germany (and elsewhere) may have tried to live according to Christian principles, but were only willing to do so internally or privately in a guarded sense. In one of his more interesting observations, Metaxas points out that Bonhoeffer was willing to make mistakes, and even sin, in his efforts to be obedient to God’s will. For Bonhoeffer, many Christians were too caught up in legalistic righteousness and allowed the German government to set the terms of the debate in consequence.

In one poignant section of the book Bonhoeffer gives the example of a teacher who interrogates a young child about his father’s drinking. In Bonhoeffer’s view, the child in this situation who lies to protect his father is justified in doing so … because the child owes the teacher no honesty.  In like vein, Bonhoeffer realized that he was willing to lie and deceive Hitler’s Gestapo if necessary, because he owed evil no morality.

This and many other things in this book made this reader want to read some of Bonhoeffer’s writings.  In the end, the story of Bonhoeffer’s life is both melancholy, and inspirational.    Metaxas’ book is one that this reviewer will think about for a long time to come.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment