The First Salute by Barbara Tuchman

Barbara Tuchman’s First Salute: A View of The American Revolution is a look at the American War of Independence from an external perspective. The coverage of events in America is almost tangential to the story Tuchman has to tell. Much of what she relates has a refreshingly different focus from other histories and biographies covered thus far at WWTFT.

Barbara Tuchman’s First Salute: A View of The American Revolution is a look at the American War of Independence from an external perspective. The coverage of events in America is almost tangential to the story Tuchman has to tell. Much of what she relates has a refreshingly different focus from other histories and biographies covered thus far at WWTFT.

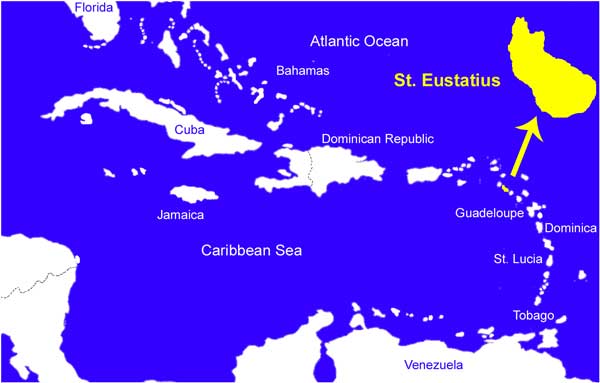

The title of the book, The First Salute, refers to the first official diplomatic recognition of the United States as a distinct, separate, sovereign entity.  On November 16th, 1776, the seemingly innocuous island of St. Eustatius, a Dutch possession in the West Indies, raised a tremendous hubbub on the world stage. That’s when the harbor’s Fort Orange fired it’s guns in salute of the Andrew Doria, an American brig flying the stripes, if not stars of the incipient nation.1 This marked the first time a foreign official formally acknowledged the sovereignty of the United States of America.2 Tuchman takes the reader on a narrative of Dutch history that provides a background of European politics leading up to the American Revolution. The history of the Dutch republic is a cautionary tale of what Hamilton warned in the early Federalist Papers.

Like the American colonists from Britain 140 years later, the Dutch fought tooth and nail for their independence from Spain. They were an industrious and innovative people who literally created the very land on which their country stood.  What the Dutch lacked, however, was unity. According to Tuchman, “Money and empire had not charms enough to placate separatism in the Netherlands and lure the Dutch toward unity … every man called himself a Haarlemer or Leydener, or Amsterdammer, identifying with his city, rather than his nation — to its loss.” They ended up with a system that was so ineffectual as to be nearly incapacitated. “Dutch government was so restricted by its method of policy making as to be as impotent as Gulliver, tied down by the strings of the Lilliputians.” John Adams must have taken home some lessons based on the frustrations that he experienced from having to deal with this government. Tuchman offers the following comparison of the two roads taken, one by the Dutch and one by the Americans.

In general, the Americans, facing many of the same decisions of statehood as the Dutch, came to more sensible solutions, no doubt because they were fortunate in the sensible and sophisticated political thinkers to whom their constitution is owed.

The Dutch discovered that national pride without the means to back it up led them into a disastrous war with far reaching consequences.  Hamilton might as well have been writing about the Dutch in Federalist 11,

In a state so insignificant our commerce would be a prey to the wanton intermeddlings of all nations at war with each other; who, having nothing to fear from us, would with little scruple or remorse, supply their wants by depredations on our property as often as it fell in their way. The rights of neutrality will only be respected when they are defended by an adequate power. A nation, despicable by its weakness, forfeits even the privilege of being neutral.

The British were predictably irritated by the Dutch trade with America, in particular that conducted through the island of St. Eustatius. At the beginning of hostilities between Britain and its American colonies, this island outpost was a critical supply depot for the American rebels. It was a primary means of conducting trade between the cash-starved colonies and Europe. At St. Eustatius, American ships could sell and barter for much needed war materiel.

When the Dutch tried to assert their trade and navigation rights as a neutral power, by proposing a doctrine of unlimited convoy (a means of protecting their shipping with armed escort), the British took this as a hostile act. This, and a secret treaty of commerce which Holland was negotiating with France and America, was too much for the ego of the British. This treaty was initially between France and America and would ensure “amity and commerce with America” and take effect when the colonies became independent. The American commissioners in Paris sent a copy to Holland in an attempt to get their agreement as well. The merchants in Amsterdam were eager not to be cut out of any trade deal with America and unilaterally pushed for its ratification.  William V, the Statdholder, leading the pro-British faction within the government, was incensed at his action and threatened to resign, when the “secret” negotiation came to his attention. Although Amsterdam merchants were motivated to support America, not all of the Dutch States were. Once again, the situation in Holland seem to mirror what Publius had to say in Federalist No. 3, about the advantages to be afforded by ratification of the Constitution.

Under the national government, treaties and articles of treaties, as well as the laws of nations, will always be expounded in one sense and executed in the same manner, — whereas, adjudications on the same points and questions, in thirteen States, or in three or four confederacies, will not always accord or be consistent; and that, as well from the variety of independent courts and judges appointed by different and independent governments, as from the different local laws and interests which may affect and influence them. The wisdom of the convention, in committing such questions to the jurisdiction and judgment of courts appointed by and responsible only to one national government, cannot be too much commended.

Holland’s lack of cohesive policy and governance drew it into a war with Britain that it was ill-prepared to fight. Britain looked at Holland with derision and amazement over it’s lack of preparedness. Britain’s Lord North told the House,

… they [the Dutch] had not acted with any degree of prudence, made no preparation for war in case of being attacked; and although they must have been aware that, in direct violation of every acknowledged law of nations, their merchants had constantly supplied Britain’s enemies with warlike stores and provisions, of which they had made the island of St. Eustatius the depot, yet they had not thought it necessary either to take any precautions against detection, or to guard against surprise by the British naval and military commanders in these seas, of whose vigilance and activity they could not have been ignorant.

In the end, their lack of unity resulted in their downfall, fulfilling the pattern that Hamilton and Jay portrayed as a likely outcome were the Constitution not ratified. By 1795, Holland’s United Provinces were incorporated into Napoleon’s France. They lost their hard-won independence after less than 150 years.

After dispensing with the Dutch, Tuchman spends most of the remaining 2/3’s of the book on the situation in Britain. She describes a politically divided country with misplaced priorities. The British displayed an astounding lack of understanding with regard to the value of the colonies in America. They placed higher importance on the islands of the West Indies than on America. They viewed the rebel colonists with disdain and were seemingly incapable of taking them seriously.

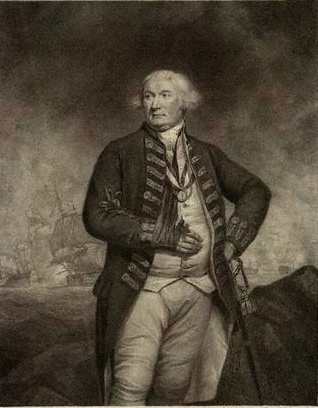

In addition to the political factions in parliament, Tuchman also writes about factions within the navy and the fact that some of the most capable officers refused to serve in the American theater. As a result, England sent a succession of geriatric admirals to command the fleet in North America. The one notable exception was Admiral Rodney. In spite of his willingness to serve, he was kept out of the fray initially because of differences with the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich.

In addition to the political factions in parliament, Tuchman also writes about factions within the navy and the fact that some of the most capable officers refused to serve in the American theater. As a result, England sent a succession of geriatric admirals to command the fleet in North America. The one notable exception was Admiral Rodney. In spite of his willingness to serve, he was kept out of the fray initially because of differences with the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich.

When he was finally called upon, and captured St. Eustatius, the island’s importance had been reduced to the point of insignificance.  By that time, France was already in the war as an American ally and was supplying most of their arms.

Tuchman provides details of both Rodney’s biography as well as some important background material on the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy was hostage to the state of the art in signaling between ships (abysmal), antiquated battle doctrines, and policies that ensured blind compliance and stifled innovation. Readers of Patrick O’Brien or C.S. Forrester will probably appreciate her descriptions of line-ahead battle formations, the weather-gauge, the Articles of War, and the impact of the inflexible fighting instructions3.  The twisted interpretations of the fighting instructions culminated in the juxtaposition of two court martial cases. In one, the admiral in question, Matthews, was found guilty of disobedience to the fighting instructions and drummed out of the navy. In the other case, Admiral Byng was executed for explicitly trying to avoid Matthew’s mistake and adhering to the fighting instructions. But, in so doing he was found guilty of failing to do his utmost to fulfill his duty, which was in contravention of Article 12 of the Articles of War.

Admiral Thomas Graves |

Admiral Samuel Hood |

The long term ramifications of the uncertainty regarding fighting instructions resulted in the hesitancy and poor decision-making by Admirals Graves (commander-in-chief of the North American Squadron) and Hood (sent by Rodney to North America in 1781, to assist Graves).

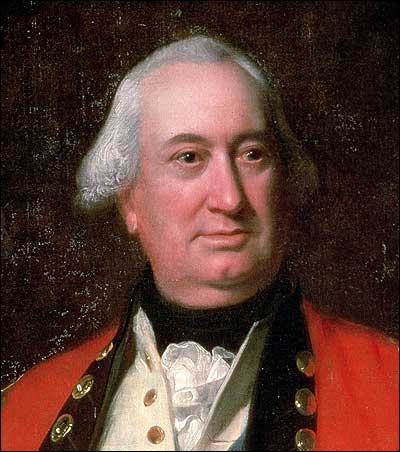

General Clinton |

General Cornwallis |

If the dysfunction of the Navy wasn’t bad enough, the battle of egos between officers and the lack of a coherent strategy seemed to typify most of the British efforts in America. Tuchman details the malaise of Generals Clinton and Cornwallis and of Admirals Hood and Graves. She also tries to explain some Cornwallis’ inaction at Yorktown as due to an expectation of promised assistance by Clinton that never materialized. She points out that Cornwallis never really believed in what he was doing, but instead chose to serve as a matter of duty.  However, ultimately her conclusions about why Cornwallis was doomed at Yorktown boils down to simple obtuseness. The British military leadership couldn’t imagine a coordinated effort between the rebel army and the French fleet.

The First Salute is a very interesting book and there is much more information than can be summarized in a review. On the whole the book was thorough and insightful with only a few minor omissions and discrepancies.

Tuchman ends the book by pointing out that America has come closer to realizing the progressive ideal of the “new man” than any other revolution in history, but that such a goal is not something that can be accomplished by revolution.

If Crevecoeur came again to ask his famous question “What is this new man, this American?” what would he find? The free and equal new man in a new world that he envisaged would be realized only in spots, although conditions for the new man would come nearer to being realized in America than they would ever come in the other overturns in society.  The new man would not be endowed with liberty, equality and fraternity in France; he would not be freed from oppression when the Russians overturned the Czars. A new man formed “to serve the people” instead of himself would not be created by the Communist Revolution in China in 1949. Revolutions produce other men, not new men. Halfway “between truth and endless error” the mold of the species is permanent. That is earth’s burden.

1The flag flown on the Andrew Doria was made in Philadelphia, not by Betsy Ross, but by Margaret Manny and “displayed 13 red and white stripes, representing the union of 13 colonies, together with the combined crosses of St. Andrew and St. George, in the canton, or upper left quadrant retained from the Union Jack.” pg. 48

2In 1939 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt presented a plaque to St. Eustatius. Mounted on the ruins of Fort Orange, it reads, “In commemoration of the salute of the flag of the United States fired in this fort November 16, 1776 by order of Johannes de Graff, Governor of St. Eustatius in reply to a national gun salute fired by the U.S. Brig-of-war Andria Doria. Here the sovereignty of the United States was first formally acknowledged… to a national vessel by a foreign official.”

3The Fighting instructions dictated that the line-ahead rule must be adhered to. This rule stipulated that ships of the line had to follow each other at a distance of about 200 yards and must engage the enemy ship by ship in their “line”.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

I have Barbara Tuchman’s book “The Guns of August“, on the outbreak of World War I. It is one of the finest pieces of historical writing I have ever encountered. Historically sound, yet it reads like a thriller! Just on that fact, I would heartily recommend this book to any reader.

[Reply]

I’ll have to add it to my (very long) list. I have read The Zimmerman Telegram by this author … many years ago.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment