Contesting Slavery: Edited by John Craig Hammond and Matthew Mason

Contesting Slavery is a collection of essays written by academic historians. The essays focus particularly on the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War.  They present a variety of view points and the authors fall into a few different schools of thought in their arguments for their particular interpretation of precisely what kind of country the Framers crafted.

Contesting Slavery is a collection of essays written by academic historians. The essays focus particularly on the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War.  They present a variety of view points and the authors fall into a few different schools of thought in their arguments for their particular interpretation of precisely what kind of country the Framers crafted.

The book is informative and packed with research and opinions (supported by voluminous footnotes) from it’s Foreword to it’s concluding essay, Commentary. In the foreword, Peter S. Onuf points out that while, “Slavery has shaped our national narrative,” it is all too easy for modern historians to oversimplify a complicated subject by letting their ideological proclivities overshadow reality. In so doing, “Revisionists thus simultaneously reject the Founders and identify with them, positioning themselves at the endpoint of the history the Founders envisioned.”

To be sure, there are some revisionists among the authors of these essays, but these are balanced with other essayists who look for a more holistic understanding of this period of American history. Some of the writers seek to make slavery the over-riding issue in the early history of the United States, others assign it to a virtual back-burner of importance during this time-span. Most appear to agree that slavery was omnipresent, that while sometimes unacknowledged, it factored into most of the major issues of the times.

Summarizing a book of this sort would entail rewriting it. Instead, we will look at some of the repeating themes in many of the essays and pick out a few interesting ones.

- Anti-slavery vs. Abolitionist

- Jeffersonian Republicanism

- Mental Gymnastics to Justify Slavery

- Ideology and Anti-Slavery Action

- Racial Consensus (Racism) vs. Conflict History

Anti-Slavery As Compared to Abolitionist

There is a difference between these two terms. The first does not necessarily equate with the second. There were many people who professed to be Anti-Slavery, but were equally opposed to outright Abolition. On the other hand, all Abolitionists were Anti-Slavery. The reasons for this distinction were various and complex. For some it was a matter of pragmatism, their first priority was maintaining the Union and outright abolition was simply too risky. Instead they sought to export freed slaves into colonies. Another argument made by non-Abolitionists was based on racism; they were fine freeing the slaves in principle, but did not want to be faced with prospect of living with them as free people.

Additionally, there were Democratic-Republicans as well as Federalists who styled themselves as Anti-Slavery without seeming contradiction. Early Federalists may not have liked slavery, but they were willing to tolerate it for the sake of harmony in the union. The Abolitionist movement came into it’s own partly in response to the complicity between parties with respect to Anti-Slavery. Several of the essayists mention the gag-rule employed by Congress (for years at a time) to table even the merest whiff of discussion of this topic.

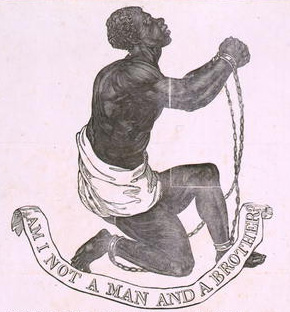

While Anti-Slavery advocates could hide behind a multiplicity of different views, the Abolitionist movement stood on the moral high-ground, viewing slavery as an inexcusable sin. Their arguments and position was polarizing and non-negotiable, ultimately only to be resolved by civil war.

Jeffersonian Republicanism – North and South

The backlash against the Federalist party gave rise to the Democratic-Republicans, later known as the party of Jefferson.  Padraig Riley’s essay, Slavery and Problem of Democracy in Jeffersonian America, might have been entitled, “Politics Makes Strange Bedfellows.” In this essay, Riley explains the reasons for the seemingly incompatible views “held” by northern party members. While there were certainly hypocritical masters (like Jefferson) who spoke of liberty at the same time they held slaves in bondage,

The large majority of white Americans, however, confronted slavery far less directly: they were neither slaves nor masters, but members of a nation in which slavery was extremely powerful and yet not always so ominously present. … for many non-slaveholders, slavery remained both geographically and ideologically distant.

Nevertheless, many leading Northern Republicans publicly opposed slavery. But their Anti-Slavery views were subjugated to their political objectives. They were “focused on their domestic battle against Federalism and the international crisis that followed the French Revolution.”

Because of the compromises that Northern Republicans made, they had to modify their Anti-Slavery convictions after 1800,

… Southern Republicans ensured that slavery would remain a central issue in national politics, by facilitating the expansion of slavery to the West and by advocating for slaveholders in the federal government. They effectively forced Northerners to either relinquish their anti-slavery principles altogether or engage in sectional conflict.

This demonstrates the difference between pragmatic Anti-Slavery and Abolitionist principles.

Mental Gymnastics to Justify Slavery

One of the interesting things pointed out in the essays of Contesting Slavery, is the degree of mental flexibility in political views applied by the many different constituencies to the issue of slavery. There were those who advocated for a strong central government as the best means of maintaining the “peculiar institution,” at the same time they fought vociferously for “states rights” to regulate and manage their domestic affairs as they saw fit. Some argued for federal laws which supported the institution by mandating restitution and the return of “property” who traversed state lines to freedom. They also argued for the expansion of slavery into new western territories.

There are probably as many ironical and inconsistent arguments made by historians on this topic as there were by the politicos of the day. Some historians subject the Framers and politicos of early American history to blistering criticism for failing to eradicate slavery, but completely ignore the reality of a weak federal government  Editor and essayist John Craig Hammond explains,

A narrow focus on the “founders” failure to prohibit slavery expansion also assumes the existence of a powerful nation-state capable of compelling the obedience of the Westerners.

…

Through 1815 — the critical period of slavery expansion in the early republic — the United States was a weak, overextended republic. … the inability of the government to compete in “the power politics of political hegemony” forced Congress to permit slavery where the white population demanded it.

Other essays discuss the impact of “The American System,” and the seemingly contradictory views surrounding “Manifest Destiny,” the American position on Cuba and Texas, as developed in Jay Sexton’s book The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth Century America.

In his essay, Neither Infinite Wretchedness, Nor Positive Good, Andrew Shankman discusses the logical gymnastics of Henry Clay trying to walk a tightrope between federal power and states’ rights. Clay fought a losing battle in his arguments for a stronger federal government to support slavery in his advocacy for political economy.

During the 1820’s, many slave owners’ fears about national power and their commitment to states’ rights intensified. …Â Those most concerned about their slave property appeared convinced that creative readings of the Constitution would allow national intervention within a state’s borders and even interference with state laws essential for the protection of slavery.

Clay was even willing to abandon the Monroe Doctrine when doing so suited his purposes in defending slavery.

There is no shortage of inconsistent argument on the topic of slavery, whether modern or contemporaneous.

Ideology and Anti-Slavery Action

Matthew Mason’s essay, Necessary But Not Sufficient, is the first to appear in Contesting Slavery. Mason challenges the revisionist view of the Founders which argues, essentially, that early Americans were a bunch of racists who did almost nothing to extirpate slavery.  He contends that reforms have to start with an idea. The results might not be immediate, but once rooted in a personal and meaningful way, people are mobilized to action.

Matthew Mason’s essay, Necessary But Not Sufficient, is the first to appear in Contesting Slavery. Mason challenges the revisionist view of the Founders which argues, essentially, that early Americans were a bunch of racists who did almost nothing to extirpate slavery.  He contends that reforms have to start with an idea. The results might not be immediate, but once rooted in a personal and meaningful way, people are mobilized to action.

Ideas hostile to slavery were thus a precondition for anti-slavery deeds, but they generally proved insufficient to move people from belief to action. Only when these ideas intersected with political, social, economic, and/or cultural factors, did anti- realize its possibilities.

…

It took a wedding of religious and Revolutionary ideas to create the first serious challenges to slavery in the would-be United States.

From the Revolution to the antebellum era, the ideology of personal liberty and equality enshrined in the United States’ founding documents had proven to be an indispensable starting point for antislavery organization. Together with a humanitarian view of Christianity, that natural rights ideology created and nourished the opposition to slavery that inhabited so many hearts and minds from the Revolutionary generation forward.

The personal, meaningful way in which different people came to terms with slavery may have been religious, economic, or practical.

It was only when the enemies of slavery could show that the institution threatened the pocketbooks, political power, civil liberties, claims to a national divine providence, national image, sectional identity, and/or security of their recruits, that their ranks swelled.

Racial Consensus (Racism) vs. Conflict History

Both the Foreword and the Commentary touch on the different historical points of view with regard to the nature of slavery in the country’s formative years. James Oakes does a creditable job in assessing and summing up some of the arguments made in the book’s essays. His main point is that slavery is not a simple topic which can be summed up by a politically motivated reading of history.

Assume that the ideology of the American Revolution, instead of being unambiguously libertarian, had contradictory implications for slavery. Fundamental human equality led in an antislavery direction, but inalienable rights of property led in the opposite direction.

Similarly, slavery persisted in the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War, not because of apathetic racists, but because of a variety of societal imperatives, which included a weak federal government, the need for union, fears of slave uprisings, states’ rights, anti-federalism, and racism.

This is not to deny the existence of white racism, but merely to urge caution in the way it is invoked. Too often race becomes the default explanation, and the racial default is too often used to explain what failed to happen rather than what actually did happen.

Oakes refers to the arguments of Matt Mason and Christopher Brown, in conjunction with insufficiency of Anti-Slavery sentiment by itself, to effect change. Anti-slavery needed to be attached to an issue that struck home for progress to be made. Similarly racism by itself was not sufficient to perpetuate slavery, but had to be coupled with economic self interest. In this his arguments echo those made by Ludwig von Mises in Omnipotent Government when discussing racism against the Jews in pre-war Germany. While always present, it was not sufficient in either case to motivate action.

Contesting Slavery is a must-read for anyone who wishes to acquire a deeper understanding of the role slavery played in the early history of the United States. It offers deeper insight into a topic which is often ignored by the right and emphasized (sometimes to the exclusion of all else) by revisionist historians of the left. Oakes concludes his Commentary on these essays about slavery in the 19th Century, by saying, “But surely an ideological consensus — over race — or anything else — will ever be an adequate explanation for that century of conflict.” Contesting Slavery does a good job in separating the ideological axe from the slavery grindstone.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

1 comment

Excellent review. I am looking forward to reading this.

Grace at Feeding My Book Addiction

[Reply]

Leave a Comment