Daniel Morgan: An Inexplicable Hero

Daniel Morgan: An Inexplicable Hero

By James Kenneth Swisher

Dr. James Swisher, inspired by the life of Daniel Morgan, wrote an engaging new biography, Daniel Morgan An Inexplicable Hero, which is being published this year posthumously by his son and family.

Daniel Morgan appears again and again in books about the American Revolution, yet many Americans are not familiar with him or his exploits. There was a time when Morgan was more appreciated, and popular authors of historical fiction like Kenneth Roberts featured Morgan in novels like Arundel (reviewed here.) He is part of the story told by John Brick in The Rifleman (reviewed here) which was the tale of Timothy Murphy, one of Morgan’s “shirt men,†so called for their buckskin attire. Both excellent books do a great job of bringing history to life.

Swisher’s book is filled with anecdotes seamlessly woven into a narrative in which countless of Morgan’s more well-known comrades appear. These include George Washington, Benedict Arnold, Aaron Burr, Patrick Henry, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams. But, Morgan’s life also intersected with William Washington, Nathaniel Green, “Mad†Anthony Wayne, and others whose names have appeared amongst the reviews featured here at WWTFT.

Swisher brings Morgan to life for the reader. Morgan was a product of his time and region – Appalachia. Swisher describes the environment thus:

The old virtues of wealth and class rank were ignored in favor of courage and physical power. While the frontier seemed a social leveler and a yardstick of equal opportunity, equality more accurately meant equal hardship, and the cunning, uncaring, and selfish were as apt to succeed as those who were courageous and industrious.

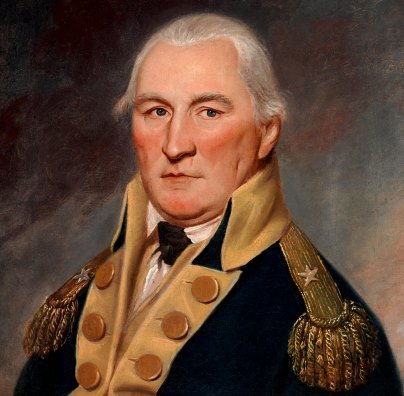

This paragraph provides an apt description of many aspects of Morgan’s character. Despite rising to the rank of General, Morgan was no aristocrat. He was a hard man, prone to profanity, and no stranger to the hardscrabble manner of resolving differences – with fists, feet, and teeth. He was tough.

Physically large and incredibly powerful, at a time when most American men didn’t exceed 5’8â€1, Morgan was almost 6’2†– about Washington’s height. He left home at the age of 17 after a “vicious argument with his father … the exact cause was unknown as Daniel refused to speak of the matter.â€

After leaving the family farm, Morgan made his way southward with little to his name but a second-hand rifle.

This long-range, lightweight killing machine was manufactured near the frontier and widely distributed early in the century. Perhaps in no other era in history was such firepower placed in the hands of the yeomen[sic] farmer. Historians have attested that in the years prior to the Revolution, the greatest number of weapon users per capita in the world populated the American southern frontier. One might also add that their unique weapon was correspondingly the world’s most effective.

Morgan soon developed a reputation for hard work that he parlayed a thriving freight-hauling business. However, Morgan also developed a reputation as a brawler. Swisher explains that Morgan frequented a rough establishment popular with wagon drivers known to its patrons as “Battletown.â€

Daniel Morgan became a regular customer, playing cards, drinking apple brandy, consorting with loose women, and fighting anyone who dared. His behavior often bordered on the unlawful, and he often faced charges in the local log courthouse. But the physically imposing Morgan was soon the area’s most outstanding frontier pugilist. He was stout, quick, high-tempered, and merciless, never conceding defeat to any opponent. This stubborn quality enhanced his future military career.

Despite the less savory aspects of his reputation, Morgan demonstrated an unusual work ethic and “a tremendous desire to succeed.†He was intelligent and observant, if illiterate. He demanded as much from his employees as he was willing (and able) to accomplish.

As in most frontier cultures, his demands were given in crude, overbearing terms, apt to be backed by his fists. Friends and cohorts became so for life, and enemies likewise.

Morgan would demonstrate his capacity for steadfast loyalty again and again, especially with regard to Washington.

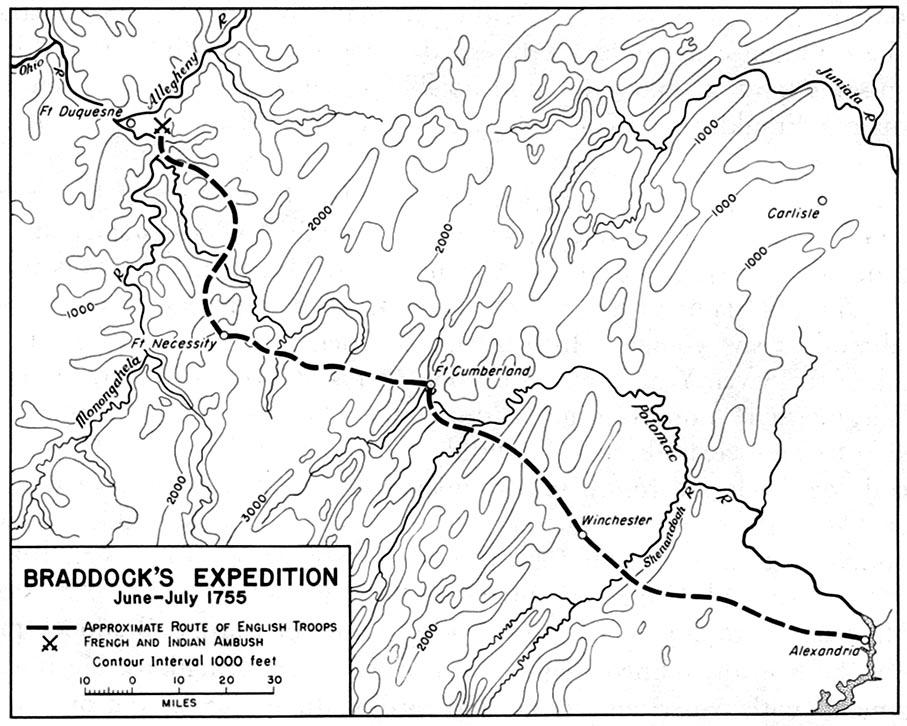

In 1755, it was this Morgan, hardworking but rawboned and sometimes crude, who “joined more than 500 teamsters in accepting contracts for hauling provisions†for the ill-fated march of General Braddock to Fort Duquesne. [see review of Braddock’s March] It is during this time that two of the earliest anecdotes about Morgan arise. One of these episodes likely influenced Morgan’s thinking about the British. An old driver named Fisher related the following story, which soon became part of Morgan’s lore:

One morning Fisher witnessed Morgan kicking awake several late-sleeping drivers and swore that if Morgan pulled such a prank on him he would taste the butt of Fisher’s long rifle. Soon Daniel passed down the line and gave Fisher a kick. The offended rose, followed Morgan and struck him in the head, driving the wagon boss to his knees. Several other wagon drivers ran up and laid into Morgan. A teen aged British Ensign arrived to investigate the ruckus just as a dazed Morgan threw off his tormentors and bound to his feet. Morgan grabbed the officer by the throat . . . thinking the young man responsible for the drubbing he had received. Within minutes a file of redcoats had bound and arrested Daniel. He was sentenced to 500 lashes for laying hands on an officer of the Crown—300 to be given on the spot until his back was raw as beef. The remaining lashes would be given on the following morning. The drummer labored hard to deliver so many lashes, and Morgan later joked that the youngster had erred and that he only received 499 strokes. King George still owed him one stroke. But the punishment was serious and for almost six weeks, Morgan lay at Fort Lewis, his very survival uncertain.

[NOTE: It is unknown (by this reviewer, anyway) if Washington witnessed the carrying out of this sentence, although it is not impossible. Morgan and the other teamsters were several miles to the rear of the train because of the slowness of the wagons over the rough terrain. Washington, suffering from the “bloody flux†(dysentery) was too ill to ride and was being transported in one of the wagons.]

Morgan now wary of British treatment of provincials, declined to participate in the second expedition to capture Fort Duquesne in 1758. (Braddock and his army were ambushed and Braddock killed. It was young, still recovering Colonel Washington who led the survivors to safety).

But Morgan ended up as an ensign in service with the Virginia Rangers that same year and led a relief column to rescue the besieged (by Indians) Fort Edward, where he remained to coordinate the fort’s defenses. The story below provides more evidence of Morgan’s incredible strength and constitution – as well as his fearlessness.

During one onslaught, Morgan slew four hostile warriors in as many minutes of hand-to-hand combat. Daniel also led the sortie that broke the back of the Indian attack. Shortly afterwards, Morgan was dispatched with an escort of two soldiers, conveying messages to the commander of the Winchester garrison. As the trio rode by Hanging Rock, a precipice with a narrow pathway high over the river, a party of French and Indian raiders assaulted them. The initial volley killed the two soldiers and severely wounded Dan Morgan. The ball that struck Dan entered the back of his neck, passed into the mouth near the socket of his jawbone, and exited through the left cheek. The missile knocked out all the teeth on the left side and the wound bled profusely. Morgan desperately clung to the mane and neck of his excited filly for he knew that to be dismounted was certain death. The spirited animal spun and raced back toward Fort Edward some fourteen miles distant. Luckily, the Indians believed Morgan mortally wounded and sent only a single rider in pursuit while the remainder looted and scalped Daniel’s dead companions. Morgan later related to his grandchildren the expression of the pursuing Indian as Morgan’s steed pulled away from him. Frustrated, the warrior pulled and threw his tomahawk but missed. When Morgan’s horse arrived at Fort Edward he was delirious and barely hanging on, his face covered in blood. He fell headlong from the lathered animal, his condition seemingly serious. But the injury looked worse than it actually was, and soon his remarkable constitution again pulled him through the medical crisis. The incident, his most serious wound, left an ugly scar that he wore as a badge of honor.

Although there are more interesting and entertaining accounts of Morgan during this period, the reader will have to read the book for those. However, the (partial) civilization of Daniel Morgan by Abigail Curry is particularly interesting. She moved in with him in 1763 over the vehement objections of her family and taught him to “read, write, and figure.†Their union produced two daughters. Morgan and Abigail were married in 1773.

In 1771, Morgan was appointed captain of the militia by Governor William Nelson. In 1774, he was appointed to raise a company of 50-60 men to support a campaign, led by Lord Dunmore, against the indians. This ended up being the “most severe, sustained Indian fight in American history.†For the sake of brevity, the details have been omitted. However, it was during Dunmore’s War, that the backbone of Morgan’s famous rifle corp was established.

For Daniel Morgan the experience was invaluable. His leadership, decision-making, and energy resulted in his enhanced reputation as an officer and, perhaps more significantly, an increased self-confidence. Daniel’s powers of observation and evaluation were again employed to his benefit and the country’s advantage. While his manner was still coarse and rough, Daniel’s mental capacity as an officer was beginning to grow. He was now a soldier.

Dunmore’s War (see Dunmore’s New World – reviewed here) in the back country was occurring at the same time as events were heating up in Boston, and the tenor of Morgan’s and his riflemen’s relationship with the British was tenuous. Self interest over the Crown’s efforts to impose restrictions on westward settlement were what mattered to Morgan and his neighbors on the frontier. The northern colonies’ concerns over trade and taxation were secondary. Thus, while both regions were uneasy with British rule, the motivations were different.

After returning from “Dunmore’s War,†Morgan returned home to work his farm.

But Daniel had long made it plain where his sympathies lay, and if it came to war, he strongly advocated the overthrow of Crown control. His militia experiences left Morgan no friend of British officers or armies.

After Lexington and Concord and the Battle of Breed’s Hill, the Continental Congress, at the instigation of John Adams, named Washington commander in chief. Shortly thereafter, Morgan also received his commission and was selected as captain of the Frederick County riflemen company. His service in the American Revolution began.

Morgan quickly assembled a company of 96 men and marched 600 miles in 22 days. They were going to Boston.

The men he led were “tough and reckless, or stubborn and relentless.â€

Only those officers who were just as tough and reckless, such as Dan Morgan, and who could and would redress them physically, could maintain a sense of duty in such a restless, combative unit of men. Unlike British military procedures, Morgan abhorred and banned flogging in his command. Soldiers whose behavior consistently violated military disciple were invited into the woods for a private “consultation†with their captain. From there they adjusted or resigned. Seldom did they face a second personal confrontation with Dan Morgan. Morgan’s company included a larger number of Germans than most of the rifle units. He developed these Palatines as soldiers better than most officers. Morgan was heard to say that the Germans fought as well as the Scotch-Irish and starved a lot better.

The rifle from which they derived their fame was a hybrid of the short-barrelled guns used by immigrant Germans in their native forests and the long-barrelled smooth-bore English fowling pieces.

The result was a slender, beautifully balanced, hybrid weapon with a lengthened, grooved barrel that permitted full burning of the powder charge, markedly increasing both range and accuracy.

Some say this weapon, which became known as the Kentucky Rifle, made the difference, although there were too few soldiers (5-10%) armed and proficient in its use for it to have been decisive on its own.. Still, in the hands of someone who knew how to use it, it was accurate and effective at up to 300 yards. (Compare this to the accuracy of the smooth bore musket used by the British forces and most of the Colonial troops – 25 yards.)2 Morgan and his men were proficient in its use. When they arrived in the camps surrounding Boston:

The riflemen set up targets and began practice routines, their accuracy observed with open amazement by the locals. One particular practice stunned the onlookers. A rifleman would stand in silhouette next to a split board while several outstanding shooters outlined his profile with rifle balls. Dan Morgan and other officers participated in this dangerous game of “William Tell.â€

But they also put their skills to practical use. Morgan soon permitted the men, dangerous when bored, to set up sniper nests and practice upon British sentries who were wholly unprepared for the deadly accuracy of the invisible riflemen.

Soon the redcoats were terrified as casualties soared, redcoats constantly being shot in the head by unseen assailants. Unaccustomed to such long-range precision, the redcoats had become careless and were paying a high price for their lack of vigilance. On one day, Morgan’s riflemen picked off four British captains. On another occasion, a quartet of Winchester riflemen discovered a dory containing half a dozen redcoats paddling across the bay. The rowers were fully 300 yards from shore and probably believed themselves beyond effective range of colonial troops. The riflemen found vantage points and fired until there was no further motion from the boat. As casualties grew, the redcoats deepened and strengthened their ramparts and embrasures, avoiding the sharpshooters. Officers discarded their gorgets and epaulets of rank and stripped off their swords in attempts to avoid rifle balls.

The British were apoplectic. This wasn’t “fair.â€

Angry protests and demonstrations swept through the British Army and back to the motherland, calling the long rifle an illegal weapon. The controversy resembled that initiated by the use of gas weapons on the western front during World War I. Newspapers, letters, and diaries were filled with vigorous condemnation of unfair tactics that sullied the honorable practice of conducting a war. William Carter, a British soldier, expressed the typical redcoat reaction of the long rifle when he stated, “It is an unfair method of carrying on a war.â€

Ultimately, owing to the shortage of gunpowder, and fearing that these depredations would precipitate an attack by the British, for which colonial troops were unprepared, Washington put a stop to the riflemen’s sport. Once again, bored and left to their own devices, the riflemen became quarrelsome disciplinary problems. At one point a fight broke out with John Glover’s Marblehead mariners (the men who would later manage the heroic crossing of the Delaware). They apparently were ridiculing Morgan’s men for their unusual attire. The fighting became so widespread that Morgan and Washington had to intervene.

Washington grabbed two combatants by the throat and butted their heads together while Morgan lay around him with his fists until a circle of riflemen lay prostrate at his feet. Repeated occurrences shamed and angered Morgan, and he grew red-faced and profane. He approached Gen. Washington to volunteer his command for another assignment. Any task far from the boring garrison duty at Boston.

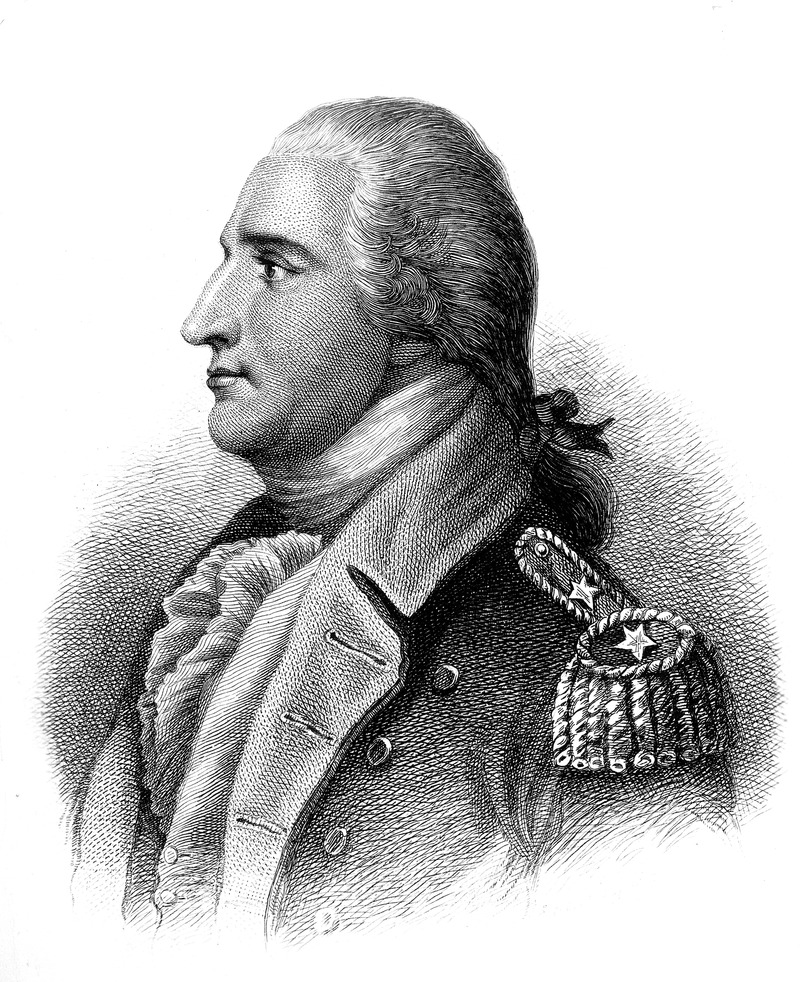

He got his wish and was assigned with Benedict Arnold for an assault on Quebec. Author/historian Kenneth Roberts details the horrendous journey through wilderness and swamps of Maine and the subsequent siege in his book Arundel. Swisher summarizes the trek:

In eight weeks 600 men had marched, waded, floated or swum 600 miles through the worst wilderness on the East Coast, a route taken that even today is considered near impassable. The trek was accomplished in the early stages of a Canadian winter, overcoming constant famine and the desertion of friends and compatriots.

The relationship between Arnold and Morgan was in some ways similar to that between Washington and Morgan. There was a difference in class between Washington and Morgan, but there was mutual respect and appreciation. Between Arnold and Morgan, the difference was not so much social stratum as Arnold’s maintenance of a social gap between him and his officers. Nonetheless, Arnold’s leadership was both impressive and critical, and Morgan would not speak ill of him even after subsequent events.

The attack on Quebec will not be detailed here, but Morgan, disguised as a French trapper, sneaked into the city on at least two occasions to scope out the defences and morale. During the (failed) attack, Morgan was conspicuous for his bravery.

Morgan took charge, raising a ladder against the barricade and quickly climbing to the top. As he looked over, a volley of musket fire literally blew him off the wall and into the snow. His hat was riddled, as well as a coat sleeve, and his face powder-burned, but fortunately he received no serious wound. Stunned, he jumped up and raced back up the ladder, diving over headfirst to land atop one of the guns. Bruising his knees badly, he rolled underneath the weapon and fought off the defenders’ bayonets with his battered old Spanish sword.

Unfortunately, Morgan and his small band were alone. Morgan’s attack was but ½ of a pincer movement, the other side of which was led by General Richard Montgomery. Montgomery was killed in the attack, along with most of his staff. Morgan was forced to abandon his efforts and surrender.

Morgan was cut off in a cul-de-sac. He placed his back against a wall, his sword his only weapon, and dared the enemy to take him, shouting insults to their manhood. Most knewMorgan, and the redcoats were reluctant to shoot a man without a firearm. They begged him to surrender, as did many of his already captured riflemen. However, Morgan continued to curse and revile his enemies until several redcoats prepared to close on him with bayonets. Finally, tears swelling in his eyes, he spotted a priest in the crowd and tossed his sword to the cleric with a closing volley of curses and insults to his foes.

Morgan would later be paroled until an exchange could be made.

Swisher provides a great deal more detail about the attack, the subsequent siege, and shows how Morgan performed tactically (“outclassed by the astute Carletonâ€) and as a leader (superb). Morgan was observant and learned from what he saw.

Throughout the book, Swisher makes occasional stops like this to analyze the significance of events and experiences to the formation of Daniel Morgan and how he became the brilliant tactician he demonstrated he was at the Battle of Cowpens.

But before Cowpens, there was Saratoga. Both Arnold and Morgan played pivotal roles in this fight, but Horatio Gates gave them no credit. Arnold grew resentful and complained loudly, and the seeds of treason were born. Morgan kept his disappointment to himself. Then, shortly thereafter, he was passed over for promotion and his beloved Riflemen given to another command. Morgan, insulted, went to Congress to resign. John Adams and others realized their mistake, and assured Morgan that opportunities for advancement would be forthcoming. Morgan’s seemingly indefatigable constitution had been strained to its limits, and he was wracked with pain from recurring fever and sciatica. He, like Arnold had sacrificed much for the patriot cause and neither man had received the recognition they deserved. But, they would take radically different paths as a result. Arnold’s perfidy, detailed in Washington’s Secret Six (reviewed here), stands out in sharp contrast to Morgan’s continued perseverance and sacrifice. Morgan would go on to become a brilliant tactician, still studied today for his innovations. Nathaniel Greene was able to learn from Morgan and replicate the success of Cowpens.

Morgan was a giant in every sense of the word. He participated in many critical events of the American Revolution (The Siege of Quebec, Saratoga, and Cowpens). He transcended his humble beginnings and earned the respect of his compatriots and his enemies. The reader is encouraged to read this fascinating account of the life of this Inexplicable Hero.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment