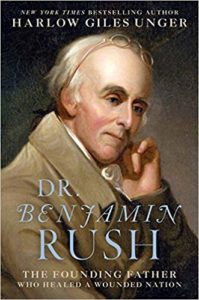

Dr, Benjamin Rush The Founding Father Who Healed a Wounded Nation

Dr, Benjamin Rush

Dr, Benjamin Rush

The Founding Father Who Healed a Wounded Nation

By Harlow Giles Unger

As one of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush qualifies as a Founder. Yet, few people today know his name. That is unfortunate because he was a remarkable man and his memory should be preserved. That is what historian Harlow Giles Unger intended by writing this biography.

Dr. Rush was brilliant, peripatetic, quixotic, utopian, visionary, impetuous, and an overachiever. But the word that describes him best is humanitarian. The author writes:

Benjamin Rush M.D. was the Founding Father of an America that other Founding Fathers forgot—an America of women, slaves, indentured workers,Laborers, prisoners, the poor, the indigent, sick and injured.

Rush was their champion; so single-minded that impatience often tarnished his pursuits on their behalf.

He received his M.D. at the University of Edinburg in Scotland and then moved to London for advanced medical studies. There he met Benjamin Franklin, then an agent for Pennsylvania. It was the beginning of a long friendship that would serve Rush well.

While still in England he applied to the College of Philadelphia for a job. Cognizant of his inadequate finances, Rush knew he would need to supplement whatever income his practice provided.

Returning to America in 1769, he began his medical career in Philadelphia.

…Without funds to open an office or buy into an established medical practice, he nonetheless walked the streets of Philadelphia determined to cure the ills of the world ——or at least those of Philadelphia’s slums——by practicing “street medicine.â€

His patients appeared to thrive. The author suggests Rush’s recommendations for better diet and hygiene had more to do with their improvement than the doctor’s ministrations. In those years medical science was rudimentary as were available instruments and remedies. Rush carried a medical kit consisting of lancets for bleeding, cloth strips for cleaning and bandaging, opium, rum and whiskey for pain, and emetics and laxatives for intestinal problems. He had many patients, but they lacked money to pay him. He was almost as poor as they were.

He was hired by the College of Philadelphia and in due course became America’s first professor of chemistry. In 1770 he published the first American chemistry text.

A Few Firsts

A partial list follows. He founded the American temperance movement and wrote tracts to further the cause. “More than two centuries ahead of his time,†he attacked the use of tobacco as a personal and public health threat. As a member of the first Abolition Society, he wrote a widely read pamphlet urging slavery’s termination.

He wrote the first study to identify Europeans as the source of venereal diseases and small pox infecting native tribes. He introduced a less painful method of smallpox inoculation learned in London. Instead of the prevailing long incision, he persuaded physicians to use a small puncture. “Within weeks the rate of smallpox in the city dropped dramatically.†The private patients attracted to the doctor’s practice were a happy by-product.

In addition, he initiated campaigns for equal rights for women, free education, slum clearance, and ending child labor. He is considered the father of psychology for recommending early forms of psychotherapy, physical therapy and medicinal treatments. The American Psychiatric Association honored Rush in 1965 by putting his portrait on its official seal.

Romance and Revolution

A descendent of Quakers who fled religious persecution in England, Rush was a natural advocate for republican principles. He threw himself into controversies over British taxation and other issues. When Thomas Paine arrived in Philadelphia from England, Rush “put some thoughts down on paper†about American independence and asked Paine to write a pamphlet based on his notes. As readers may have guessed, the pamphlet was Common Sense—“even using the title Rush said he had suggested.â€

Somehow, while ministering to the poor and pursing a multitude of noble causes, Rush found time for courting. In January of 1776 he married the lovely Julia Stockton at Princeton. He was elected to the Continental Congress the same year. And on August 2nd he was one of the 56 members who signed the Declaration of Independence. â€He was the only MD on he list.â€

Somehow, while ministering to the poor and pursing a multitude of noble causes, Rush found time for courting. In January of 1776 he married the lovely Julia Stockton at Princeton. He was elected to the Continental Congress the same year. And on August 2nd he was one of the 56 members who signed the Declaration of Independence. â€He was the only MD on he list.â€

After a few days of wedded bliss Rush returned to Philadelphia, leaving his bride with her parents at the family’s estate in Morven.

Having first treated wounded soldiers as a volunteer, he was appointed physician-general of the Middle Department of the Continental Army in 1777. He was responsible for an area stretching from the Hudson to Potomac Rivers, in charge of “military hospitals.†Almost immediately after touring his domain, Rush began writing critical pamphlets assailing the accuracy of that designation. He asserted “ a greater proportion of men perished with sickness in our armies than have fallen by the sword.“ He criticized everything from army uniforms to unsanitary camp conditions. He railed against rampant waste and speculation among suppliers of essential goods. He wrote letters to General Washington, Congress, John Adams and anyone else he thought could obtain the supplies and reforms he demanded. The recipients of his letters had bigger problems and did not take time to respond.

Rush was angry that George Washington failed to reply. He sent a scathing account of the General’s “administrative failures†to Virginia Governor Patrick Henry. The doctor was unaware that Washington was under attack by a cabal of ambitious senior officers trying to demote him. Not for the last time, Rush’s impetuousness got him into serious trouble.

Rush was angry that George Washington failed to reply. He sent a scathing account of the General’s “administrative failures†to Virginia Governor Patrick Henry. The doctor was unaware that Washington was under attack by a cabal of ambitious senior officers trying to demote him. Not for the last time, Rush’s impetuousness got him into serious trouble.

…Patrick Henry made one of his most important and little–known decisions of the Revolutionary War: he sent the letter he received from Rush by express–rider to Washington at Valley Forge.

Washington responded with grateful thanks and for the first time revealed to Henry the desperate condition at his encampment. Henry immediately sent nine privately owned wagons of clothing and blankets to Quartermaster General Thomas Mifflin to deliver to Valley Forge. The goods never arrived. In the weeks that followed Henry learned that Mifflin was diverting supplies to his own warehouses to sell to local merchants at a handsome profit.

Mifflin resigned in disgrace as a result of the ensuing scandal. He admitted to participating in the scheme against Washington. Congress replaced Mifflin with Major General Nathaniel Greene and gave Washington the power he needed to conduct the war as he saw fit.

Although Rush was not involved in the plot against Washington, the timing of his complaints led the press and George Washington to assume that Rush was a conspirator. He was summoned to appear before an angry Congress. Already charged with treason by the British government for having signed the Declaration of Independence, he now faced treason charges by the American government he had helped create.

Fortunately for Rush, events worked in his favor and he was able to mend relations with Washington, Adams, Henry and Congress. He resigned from the army in 1778 and “published Historic Proposals For Saving Soldiers Lives.â€

Rush was 32, his career in the military over, and out of work. The British army occupied Philadelphia where he had hoped to resume his medical practice. His father-in-law urged him to become an attorney. But the news that the British were evacuating Philadelphia made that suggestion irrelevant.

Back to Philadelphia

The British evacuation of Philadelphia reawakened passions that Rush still harbored for treating the sick and helping the disadvantaged …He all but leapt onto his horse and spurred the beast toward Philadelphia to re-enter the lists in combat against disease and injustice.

The British left mounds of rubbish and debris littering the streets of Philadelphia. Men previously employed by the British Army were unable to support their families. Property values plunged at the same time as bankruptcies soared. When Rush was unable to persuade city officials to help, he called on Benjamin Franklin. With Franklin’s backing Rush opened the Philadelphia Dispensary for the Poor in 1786. During the first five years of its existence, Rush treated more than 7,000 indigent patients at his own expense, much to the detriment of his family’s finances.

The British left mounds of rubbish and debris littering the streets of Philadelphia. Men previously employed by the British Army were unable to support their families. Property values plunged at the same time as bankruptcies soared. When Rush was unable to persuade city officials to help, he called on Benjamin Franklin. With Franklin’s backing Rush opened the Philadelphia Dispensary for the Poor in 1786. During the first five years of its existence, Rush treated more than 7,000 indigent patients at his own expense, much to the detriment of his family’s finances.

Between 1787 and 1789 Rush served as a delegate to the Pennsylvania Constitutional Ratification Convention and resumed social reforming. Typical of the doctor’s utopian fantasies, he expressed disappointment that the new Constitution did not establish â€an office for promoting and preserving perpetual peace in our country.â€

He was named professor of Medicine at the College of Philadelphia and published the first volume of what was to become the four volume “Medical Inquiries and Observations.†The books were drawn from notes and treatments recorded during his years of medical practice.

Any catalogue of the doctor’s humanitarian deeds must include at least a mention of his heroic efforts in behalf of the victims of the 1793-4 Yellow Fever epidemic. His treatments were ineffective (although Rush argued otherwise), but he stayed to treat the sick when all but a few doctors fled the city. He almost lost his own life in the effort. No one at the time knew the cause was mosquitoes.

About the Family

Despite long periods of time apart from his wife, Rush fathered 13 children between 1777 and 1801. Four died during infancy and all but one led happy, productive lives. The heart-breaking exception was his oldest son, John, who lived out his years confined in a sanatorium for the mentally ill.

By all accounts, wife Julia was an able and resourceful woman. During Rush’s frequent absences she managed their brood and, after her fathers death, the family estate.

As Rush was inciting a social revolution in Philadelphia, Washington was in Yorktown, Virginia putting an end to the political and military Revolution with a savage charge by American troops that crushed British resistance…

…But to Julia’s growing annoyance, even war’s end had not ended Rush’s summertime absences from his family. He seemed to meddle in every conceivable service to society but that of his own family.

More than Biography

Benjamin Rush’s life encompassed major historical events, some in which Rush played a role, others he witnessed. His friendships and correspondence with the more famous Founders augments this book beyond ordinary biographies

The exchange of letters between Adams and Rush at the beginning of 1805 started what would be eight years of uninterrupted correspondence between the two Founding Fathers—-a historical treasure …

…The Rush-Adams letters exposed and discussed in depth the range of early American history and early nineteenth-century life, including ordinary chitchat about their own family lives.

The exchange with Adams prompted Rush to try to heal the rift between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. He wanted to reconcile the two aging Founders before it was too late. Characteristically, Rush enthusiastically embarked on a letter writing campaign. He wrote to both gentlemen in turn, encouraging each man to contact the other. Their responses disappointed, each recited past wrongs committed by the other. As the end of summer approached, Rush wrote what he hoped would overcome Adam’s obstinacy.

“The time cannot be very distant when you and I must both sleep with our father’s, Rush wrote, citing an “epistolary discourse†with Jefferson as essential to emendation of accumulated historical inaccuracies about the Revolution and subsequent administrations that governed the new nation.

Not long after, Jefferson sent Rush an account of a neighbor’s visit to Adams. On that occasion, John Adams denied animosity toward Jefferson. Reportedly Adams said, “I always loved Jefferson, and I still love him.â€

That was enough for Jefferson.

I only needed this knowledge to revive all the affections of the most cordial moments of our lives…with a man possessing so many estimable qualities.

Why should we be separated by mere differences of opinion in politics, religion, philosophy or anything else? His opinions are as honestly formed as my own. I wish therefore …to express to Mr. Adams my unchanged affection for him. (Emphasis his)

And so began an exchange of more than 150 letters over fourteen years from 1812 to their deaths in 1826. Rush was overjoyed. He had healed one of the Nations greatest political wounds.

And so began an exchange of more than 150 letters over fourteen years from 1812 to their deaths in 1826. Rush was overjoyed. He had healed one of the Nations greatest political wounds.

“ Few of the acts of my life has given me more pleasure,“ He wrote to Jefferson, “than to hear of a frequent exchange of letters between you and your old friend Mr. Adams.â€

Space prevents expounding further on Dr. Benjamin Rush’s amazing accomplishments, (only interstellar travel is missing). This reviewer hopes this erudite and wide-ranging book will provoke interest hitherto lacking.

Notes:

Unger provides additional information about Benjamin Rush’s life and work in the Index portion of the book.

Appendix A: Selected Writings of Benjamin Rush by Topic.

Appendix B: Medical; Observations by Benjamin Rush, and Appendix C: Essays, Literary, Moral & Philosophical.

Appendix C: Essays: Literary, Moral & Philosophical.

Of special interest to many may be the earlier letters (in the book) between Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Rush regarding the former’s religious beliefs. This was a topic of controversy during Jefferson’s lifetime and remains so now.

Appendix D: Thomas Jefferson’s Syllabus Of An Estimate Of The Merit Of The Doctrines of Jesus, Compared With Those of Others’.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment