FDR Goes to War by Burton W. Folsom, Jr. & Anita Folsom

He blamed unregulated business greed for the economy. He waged class warfare, making Wall Street bankers and corporate leaders scapegoats for the nation’s problems. He called corporations “malefactors of wealth.â€Â He promised to create a fairer, more equitable society.

He blamed unregulated business greed for the economy. He waged class warfare, making Wall Street bankers and corporate leaders scapegoats for the nation’s problems. He called corporations “malefactors of wealth.â€Â He promised to create a fairer, more equitable society.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was an early adherent of Rahm Emanuel’s philosophy regarding crisis and opportunity. With unemployment at almost 20%, Roosevelt used fear and economic uncertainty to breach the Constitution with an alphabet soup of overlapping interventions in the economy.*

Roosevelt radically altered the relationship between citizen and government in America, and not for the better. With enhanced executive power, Roosevelt rewarded friends and punished enemies for his own advantage, morally corrupting the office of president. Readers will learn about all of the above and much more from FDR Goes to War.

It is evident that Barack Obama has not only adopted FDR’s political strategies, he has worked throughout his presidency to further extend the economic policies, controls, massive spending, and tax policies Roosevelt launched. This important book penetrates the shield of hagiography erected by leftist journalists and historians to reveal how those policies came about and what they accomplished.

FDR and his New Dealers had a special system for mobilizing the WPA (Works Progress Administration) to win elections. During election years, they had increased WPA rolls (and those of other federal programs as well). Those who received government jobs were grateful and were expected to campaign vigorously for Democrats on Election Day. After the election, the WPA laid off workers because they were not needed until the next campaign, thereby cutting some federal spending to make the budget deficits look smaller. Some members of Roosevelt’s cabinet were nervous about moving poor Americans on and off the WPA for political purposes.

The authors point out that members’ occasional qualms did not overcome their determination to get FDR reelected. Roosevelt was reelected four times, but despite the billions poured into New Deal programs, the economy remained stubbornly stagnant. What he did accomplish during his first two terms was to grow the national debt faster than any previous peacetime president.

He spent lavishly on new programs while slashing defense spending. Regardless of ominous events in Europe, he reduced the army, refused to replace outworn WWI equipment and cut appropriations for the War Department. He also manipulated public opinion and searched for a “’flash point,’ an international incident that would goad the American public into demanding war.â€

Even before taking office in 1933, FDR favored war with Japan “now rather than later,†as he told a confidant. Most Americans, however, appalled by new revelations of the slaughter of WWI, favored an isolationist foreign policy.

On becoming president FDR kept his views about Japan to himself and concentrated on the economy. He saw no urgency in training large numbers of men or replacing antiquated weapons. He believed men could quickly be converted from “mechanical trades†to the military. He knew nothing about military realities and his egoism coupled with his primary political considerations were almost fatal to America’s war preparedness.

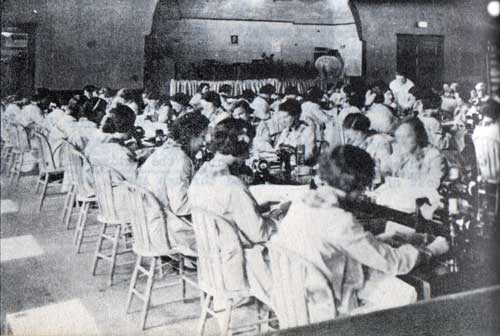

Roosevelt made the military a stepchild of the New Deal. He used some WPA and the CWA (Civil Works Administration) workers for military projects, upsetting administration progressives, but garnering votes in the favored districts.

Hitler‘s rapid military successes took FDR by surprise. As Hitler’s troops swept through Belgium, Holland and France, General George Marshall and several cabinet officers pleaded with FDR to allow Marshall to ask Congress for a large increase in defense appropriations. But with elections less than 6 months way, FDR was leery of appearing too war-like, having promised to keep America out of the war. Marshall’s arguments prevailed and FDR asked Congress for more than a billion dollars to deliver much needed armaments to the nations fighting Hitler. Congress complied, belatedly recognizing that the defense of the Western Hemisphere had become a top priority.

In Roosevelt’s May 26, 1940 Fireside Chat, he abandoned his previous anti-business rhetoric. No more would he refer to corporate heads as ’privileged princes’ who were ‘thirsting for power.†Times had changed. FDR offered federal “partnerships†and incentives to American industrialists for converting their factories to manufacturing the munitions needed to defeat Hitler and his allies. To win the war he would suspend antitrust laws and allow corporate leaders to share ideas and personnel.

The authors explain that presidents could fail to end depressions and still survive politically if they had a viable scapegoat. FDR had proven that. But losing wars was another matter. Historians would hold him accountable if that happened on his watch. To save his legacy he would embrace big business to arm the United States. However for the sake of the 1940 elections, FDR would continue to pretend that America could stay out of the war, while buying time to rebuild defenses.

When war did come, Roosevelt’s lack of preparedness became apparent. He had underestimated the Japanese, and their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor devastated the American Navy and exposed the president’s incompetence.

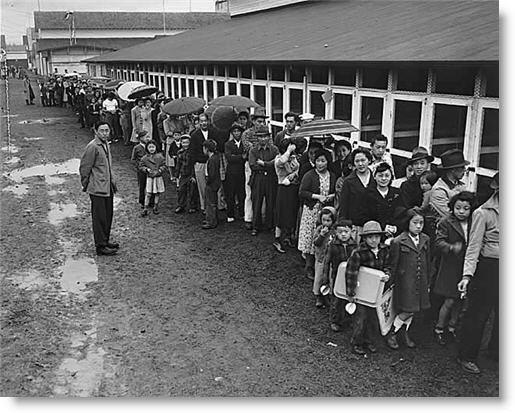

He used the war as an excuse to seize private property; conducted illegal wiretaps of political opponents; attempted to silence members of the press he had not already seduced with flattery or favors and, most egregious of all, interned 110,000 Japanese-Americans, despite assurances by J. Edgar Hoover and others that they were overwhelming loyal.

Such a violation of the Constitution was unprecedented in U.S. history, and Roosevelt had a variety of pressures that led him to make such a decision. Alleged ‘military necessity’ was one, but political expediency was another.

Western states racist groups had long opposed Japanese immigration and many farmers resented the competition. It is telling that Roosevelt never considered interning German and Italian immigrants, even though we were at war with their countries.

In Roosevelt’s political calculations, he wanted votes from German-Americans and Italian-Americans. He also wanted to carry California and the western states. By relocating only the Japanese–Americans, he could please native Californians, and not offend the many ethnic Germans and Italians he would need to win reelection in 1944.

The Folsoms also shine light on FDR’s policy regarding the rescue of European Jews. After the fall of France, Jewish émigrés, desperate to save those still trapped across the Atlantic, appealed to Eleanor Roosevelt to persuade her husband to grant the necessary visas.

Roosevelt’s policy on Eastern European immigration reflected that of he State Department, which argued, “If these people were in trouble, then they must be troublemakers–probably ‘Reds’ of Nazi spies–not the kind of immigrants that Americans wanted.

Roosevelt gave lip service to saving the imperiled Jews but followed the advice of Breckinridge Long, an old friend and contributor to his presidential campaigns.

â€In June of 1940, Long wrote:

We can delay and effectively stop for a temporary period of indefinite length the number of immigrants into the United States. We can do this by simply advising our consuls to put every obstacle in the way and to require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative devices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas’ …Literally tens of thousands of available visas were never used at US consulates, under orders from Washington.

Roosevelt’s conduct of foreign policy was also disastrous. FDR liked and trusted Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, despite Churchill’s warnings.

The Folsoms report that Roosevelt was enchanted with what he thought was the Russians’ worldview. In a conversation with Francis Perkins, the secretary of Labor, FDR commented, “They all really do what is good for society instead of wanting to do for themselves. We take care of ourselves and think about the welfare of society afterward.†In another conversation with Ambassador William Bullett, Roosevelt elaborated, “I think if I give him everything I possibly can, and ask nothing from him in return noblesse oblige, he won’t try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of peace and democracy.’â€

Roosevelt ‘s self-confidence was boundless. He thought he could negotiate, placate and charm Stalin into becoming a democrat.

By March 1944… as Stalin’s Army approached Poland, the Poles in America began to worry about what Roosevelt might have given away at Teheran, and how he felt about Poland’s independence.

Roosevelt publicly assured them that Poland would be fine. However, some Polish-Americans were vocal about their doubts. With the November elections looming, FDR invited a Polish-American delegation to the White House for a personal meeting and press photos. The old Roosevelt charm carried the day.

Roosevelt won almost 96% of Polish-American votes– “and he didn’t have to meet with Stalin for four more months, at which time the Polish-Americans would finally begin to learn the bad news about Stalin’s real intentions and Roosevelt’s grand concessions to him.”

The authors address a question that has long threatened to sully Roosevelt’s legacy.

Did FDR specifically and knowingly allow Pearl Harbor to be attacked so that he could ask for a declaration of war from Congress? The answer is no. Research shows that Roosevelt was sure the Japanese would attack; the question was where? And he, like most other strategists, believed that they would attack Singapore and probably the Philippines. That Roosevelt and most military leaders grossly underestimated, or even ignored the capabilities of aerial attack is undoubtedly true. That Roosevelt and (Cordell) Hull (Secretary of State) could have come to some agreement with the Japanese that would have delayed the war and given the United States more time to prepare is true. And that Roosevelt squandered billions of dollars on pet New Deal projects in the eight years leading up to Pearl Harbor while allowing the military to languish with archaic equipment is also true. Roosevelt’s incompetence in both foreign policy and military planning certainly contributed to the disaster, but he did not plan or desire the devastation at Pearl Harbor on December 7.

The authors also point out that FDR’s leadership during the war was often evasive and self-serving. His naïveté and egoism resulted in the communist domination of Eastern and Central Europe with all that portended. On this side of the Atlantic, the war laid the groundwork for permanent government expansion.

To fund the war and his planned economy, Roosevelt secured a large and regular supply of revenue by raising taxes and requiring the withholding of pay. Before the war, fewer than 5% of Americans were required to pay income taxes. By the end of the war, the number jumped to about 65% of adultAmericans … and the top rate was 94% of all incomes over $200,000.

FDR was, beyond question, an enormously effective communicator. He used his Fireside Chats to reassure and unite the nation behind winning the war. To his credit, he secretly funneled arms to a beleaguered and increasingly desperate England. Whatever his failings, and they were legion, he believed in American ascendency and its commanding position in the post war world, even as he envisioned himself commander.

FDR Goes to War is surprisingly short, (313 pages, plus another 57 of sources), considering the wealth of available material. It should become a point of departure for other, more extensive, examinations of FDR’s policies. This book should be widely read because it reveals the origins and, especially, the results of those policies. This reviewers’ only complaint is the absence of photographs. For the majority of readers whose memory banks do not hold the many unique images of the period, the text would have been wonderfully amplified had they been included.

*Among them: the Emergency Banking Act (1933), the Economy Act (1933), the Federal Securities Act (1933), the Tennessee Valley Authority (1933), the Civilian Conservation Corps (1933), the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (1933), the Glass-Steagall Act (1933), the Civil Works Administration (1933), the Public Works Administration (1933), the National Recovery Administration (1933), the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (1933), the Farm Credit Administration (1933), the Federal Housing Administration (1934), the Gold Reserve Act (1934), the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (1934), the Works Progress Administration (1935), the Public Utilities Holding Company Act (1935), the Social Security Act (1935), the National Labor Relations Act (1935), the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act (1936), the National Housing Act (1937), the Farm Security Administration (1937), and the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938).

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment