First Entrepreneur by Edward G. Lengel

Edward Lengel portrays a side of Washington that is frequently referenced in other books, but not explored to the degree of the First Entrepreneur. Lengel’s Washington starts out more Jeffersonian than the typical biography of the man Harry Light Horse Lee eulogized as “first in peace, first in war, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” The Washington in Lengel’s book is, of course, an entrepreneur, and while not an inventor, like Franklin, was an inveterate tinkerer. Washington’s interests ranged far and wide. As authors like Chernov have pointed out, Washington was keenly aware of his lack of formal education and spent a great deal of time and effort filling in the gaps. His library may not have rivaled that of Jefferson, but was substantial and impressive. Its subject matter focused on the practical more than the theoretical.

Edward Lengel portrays a side of Washington that is frequently referenced in other books, but not explored to the degree of the First Entrepreneur. Lengel’s Washington starts out more Jeffersonian than the typical biography of the man Harry Light Horse Lee eulogized as “first in peace, first in war, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” The Washington in Lengel’s book is, of course, an entrepreneur, and while not an inventor, like Franklin, was an inveterate tinkerer. Washington’s interests ranged far and wide. As authors like Chernov have pointed out, Washington was keenly aware of his lack of formal education and spent a great deal of time and effort filling in the gaps. His library may not have rivaled that of Jefferson, but was substantial and impressive. Its subject matter focused on the practical more than the theoretical.

The purposefully directed, bricks-and-mortar reading style reflected Washington’s growing conviction that economics was the fundamental reality that underpinned everything else, included politics and war.

It seems that Washington understood the link between political freedom and economic freedom. Nearly two centuries later Frederich Hayek would explain, in the Road to Serfdom, (reviewed here) that economic freedom is intricately tied to political freedom.

To be controlled in our economic pursuits means to be always controlled unless we declare our specific purpose. Or, since when we declare our specific purpose we shall also have to get it approved, we should really be controlled in everything.

Lengel states that Washington was intrinsically aware of this relationship having learned it first-hand via the political crises of the 1760’s and 1770’s.

His [Washington’s] actions and words demonstrated his belief that political prosperity depended on economic prosperity, and that political freedom depends on economic freedom.

The line between economic freedom from Britain’s taxes and enforced monopolies on trade and shipping, and political freedom was nearly erased by 1775. Britain wanted the colonies to pay their share, as they saw it. When the colonies did not acquiesce, the British government resorted to progressively more forceful measures. In later years Washington is sometimes (dubiously) attributed to have said,

Government is not reason, it is not eloquence — it is force. Like fire it is a dangerous servant and a fearful master; never for a moment should it be left to irresponsible action.

Regardless of the accuracy of the attribution, Washington knew this to be true.

Military conflict threatened Washington’s personal ruin as well as America’s economic destruction. … It is a measure of both Washington’s realism and of his belief in the cause that he accepted the risk not just to participate in the war but to lead the army.

Lengel ties Washington’s innate understanding of economic principles to Washington’s role as Commander in Chief in other ways than merely knowledge of the causal linkage between war and economics.

Washington hated debt, and while he had a taste for the finer things, in the 1760’s and 1770’s he limited his consumption of imports from Great Britain to necessities, eschewing luxuries. This dovetailed with his growing conviction that the colonies needed to become more self-sufficient.

Washington’s resolution in the wake of the Stamp Act crisis to live within his means while aggressively building his fortune ideally suited him as a symbol of America’s quest for economic freedom.

This self-sufficiency would enable Washington to serve for duration of the war without salary. This is all the more remarkable because Washington knew that the war might well wreck his personal estate. While Washington did not accept a salary, he stipulated that his expenses, scrupulously documented (Lengel refers to Washington as a “fanatical account-keeper”), be reimbursed at the successful close of the conflict. In effect, Washington not only served without remuneration, he helped finance some of the war, at considerable physical and financial risk to himself.

Washington’s understanding of economics also factored in to his strategic vision.

… He also believe that beneath the clash of arms the conflict was fundamentally economic in character, and that the national fiscal health was the yardstick of military success. This outlook was vital to his strategic vision. Keeping in mind that economic freedom and prosperity were ultimate objectives, he sought to carry on the fight without undermining the foundations of future growth.

Winning the war, in other words, could not come at the price of losing the peace that followed. Building and maintaining a politically stable, democratic government would create a framework in which the economy could flourish. Conversely, establishing a functional economy and ensuring that it not collapse under the strains of war would ensure stable government. …

Lengel asserts that Washington utilized his experience as administrator of Mount Vernon in his management of the Continental Army. Many of the habits gained from his business dealings directly translated into his military life.

Transparency was one such characteristic not commonly shared among his contemporaries.

Many of his acquaintances and business associates were in the habit of juggling accounts to obscure secret expenditures or investments–or, more often, to hide fiscal embarrassments. No one could ever justly accuse Washington of such deceits. Probity and openness, he knew, built the trust essential to establish and maintain personal credit….

This quote might reflect a bit of the author’s bias. No reasonable student of Washington can deny the importance of his role, the overall excellence of his character and his constant struggle to reflect and demonstrate virtue. However, Washington was human and did struggle mightily with the conflict between self-interest and the public weal. Most of the time he was successful.

“Few public figures in American history could match Washington’s record of virtuous and selfless service, but even he stumbled when the vast potential of the frontier West was at stake….That personal considerations, from the potential enhancement of his Mount Vernon properties to the added value that would accrue to the real estate he owned in Alexandria, should now have entered his thoughts can hardly come as a surprise. As always, he convinced himself that the nation was the chief beneficiary of his actions. If that was not quite the case, it nevertheless would be difficult to argue that the national interest was in any way harmed by his conduct.â€1

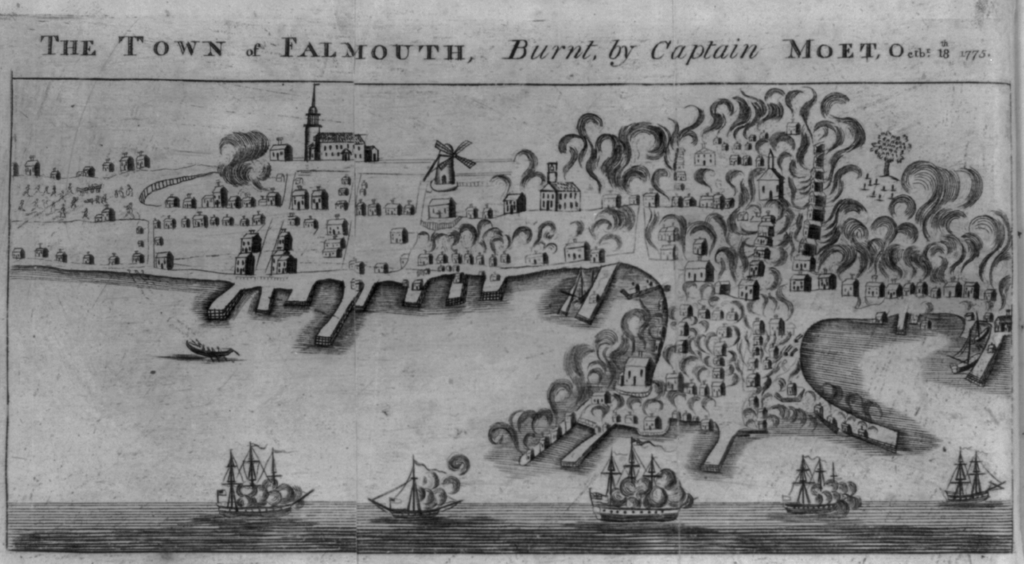

Struggles or rationalizations of self-interest notwithstanding, Washington played upon his strengths. His understanding of the importance of the concept of private property was another economic principle that governed Washington’s conduct of the war. While it was true that British prohibitions on further westward settlement personally affected Washington, it would be unjust to ascribe too much significance to this. The attacks on Falmouth (1775) and Norfolk (1776) were in Washington’s eyes an attack on the principle of private property and infuriated him.

… Washington assumed that Norfolk was the dreaded next step in a British campaign against American property and commerce. In reaction, he began for the first time to to speak of “the Propriety of a Seperation” [sic] from Great Britain. In breaching the sacred principle of private property in a war against its own citizens, the ministry had renounced its right to govern. For Americans, it was no longer an option but a necessity to “shake off all Connexions with a State So unjust & unnatural.”2

Economist Ludwig von Mises (see review Omnipotent Government) would state it thusly,

Social cooperation and division of labor can be achieved only in a system of private ownership of the means of production, i.e., within a market society, or capitalism. All the other principles of liberalism, democracy, personal freedom of the individual, freedom of speech and of the press, religious tolerance, peace among the nations are consequences of this basic postulate. They can be realized only within a society based on private property.3

Lengels book succeeds in showing how Washington’s acumen as a businessman complemented his leadership throughout the war and during his presidency. He was able to balance and leverage the human propensity for self-interest with the public interest and harness the one to support the other. He did not delude himself with grandiose expectations that people would behave altruistically. Throughout the war, Washington was ruthless in his efforts to root out corruption. He saw the devastating impact on his troops. Nevertheless, he also recognized that virtue had to play a role as well.

Lengel points out a primary theme in Washington’s inaugural address,

… this was morality, and its place in the success of the great American experiment. Nature itself ordained morality in Washington’s worldview, and it fueled the work ethic of enlightened people left free to pursue their own interest. They would inevitably be industrious. In turn, their industry promoted private virtue even as it generated wealth. The process was self-sustaining; government need only clear the stage. Such was Washington’s meaning when he declared hopefully that “the foundations of our national policy, will be laid in the pure and immutable principles of private morality” and “that there exists in the economy and course of nature, an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness.” These were the principles that would inspire his conduct as president.

Lengel’s book is an interesting and novel approach to delving into the complexity of a virtuous man.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

1 comment

Lengel’s book is the BEST! I read it as a part of the residential program at Mount Vernon a couple of summers ago and had the privilege to hear him speak! I have referenced ‘First Entrepreneur’ on multiple occasions while teaching my history courses!

[Reply]

Leave a Comment