Introducing Dr. Benjamin Church Jr.

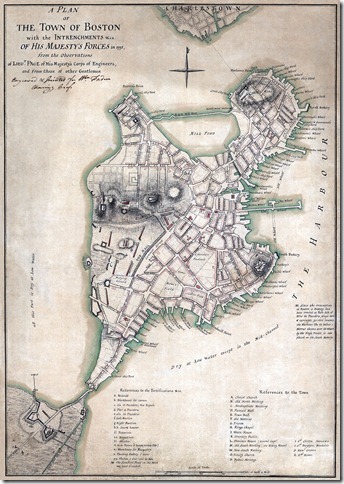

Colonial Boston was a different city topographically than modern day Boston; successive efforts to level its many hills and expand the city with landfills have made it a much different city. 1770’s Boston was a peninsula connected to the rest of the mainland by a neck of land so narrow that the city was a virtual island. Bostonians were surrounded by water and in the winter and spring had to deal with strong icy winds blowing across from the harbor or from the Charles River. Early March was an especially miserable time of the year for the citizens of Boston; weary from four months of winter, they faced at least another month of windy and cold weather, with a “nor’easter†likely to rise up out of the Atlantic Ocean at any moment and drop a foot or so of snow on the city.

Colonial Boston was a different city topographically than modern day Boston; successive efforts to level its many hills and expand the city with landfills have made it a much different city. 1770’s Boston was a peninsula connected to the rest of the mainland by a neck of land so narrow that the city was a virtual island. Bostonians were surrounded by water and in the winter and spring had to deal with strong icy winds blowing across from the harbor or from the Charles River. Early March was an especially miserable time of the year for the citizens of Boston; weary from four months of winter, they faced at least another month of windy and cold weather, with a “nor’easter†likely to rise up out of the Atlantic Ocean at any moment and drop a foot or so of snow on the city.

Colonial Boston was also a city dominated by its church steeples. On Friday, March 5th, 1773, the steeple of the largest church in the town was of special interest, for this day was the third anniversary of what, in a brilliant piece of revolutionary propaganda, came to be known as the “Boston Massacre.†The Old South Meeting House, built in 1729 by descendants of the Puritan Fathers, was the largest building in colonial Boston and was regularly used for town meetings and events that attracted too large a crowd for Boston’s Town Hall. This church could hold 5,000 people, a remarkable figure considering that the 1765 Boston census detailed a town population of 15,520 in 1,676 homes and 2,069 families. But Boston’s population on any given day was swelled by the fact that it was a port city that serviced the British Navy and a constant stream of merchant ships and their crews. In addition, Boston served as the commercial and governmental hub for the surrounding towns and was filled with a constant stream of visitors from these towns. Large meetings were held in the daytime; street lights, lighted by oil and available by subscription were only to be introduced in Boston later in 1773.

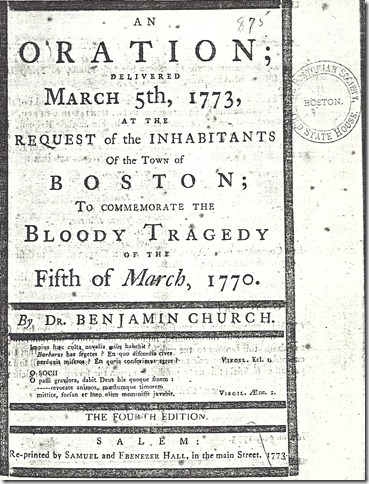

There already had been three speeches (two in the first year by Dr. Thomas Young and one by schoolmaster James Lovell) on the anniversary of the Massacre two years prior. In 1772, the speech was given by Dr. Joseph Warren, prominent physician, close associate of Samuel Adams and rising political force. On this third anniversary, Dr.Benjamin Church Jr., also a prominent physician and Whig and rising political force, was to give the eagerly anticipated afternoon speech. On this day, church bells would peal from 9:15 to 10:00 AM and in the evening, an illuminated lantern with memories of the †bloody five†who had fallen that fateful day was displayed in a balcony for all to see.

Most Americans today are familiar with Samuel Adams, so he needs no introduction. (Adams never gave one of the commemoration speeches because he was a man more comfortable behind the scenes, but, more importantly, suffered from a tremor that affected his hands and voice, and was thus not a good public speaker.) Dr. Joseph Warren is well known to most New Englanders, but perhaps not to most Americans. He eventually became President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and several days after receiving a commission as a major general in the Massachusetts militia forces, was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill, leaving his motherless children orphaned and penniless. It was Warren who sent Paul Revere on his famous ride. Dr. Benjamin Church Jr, if known at all, is known as the man who tried to smuggle a ciphered letter to his brother-in-law in besieged Boston and is believed to have been a paid informant for the British Commander, General Thomas Gage. But, on this day, Dr. Church was to deliver a speech that would solidify his position as one of the top Patriot leaders. Indeed, by April 1775, the three most prominent Boston Whigs were Adams, Warren, and Church; not John Hancock and certainly not the cantankerous, argumentative, and grumpy John Adams.

Most Americans today are familiar with Samuel Adams, so he needs no introduction. (Adams never gave one of the commemoration speeches because he was a man more comfortable behind the scenes, but, more importantly, suffered from a tremor that affected his hands and voice, and was thus not a good public speaker.) Dr. Joseph Warren is well known to most New Englanders, but perhaps not to most Americans. He eventually became President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and several days after receiving a commission as a major general in the Massachusetts militia forces, was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill, leaving his motherless children orphaned and penniless. It was Warren who sent Paul Revere on his famous ride. Dr. Benjamin Church Jr, if known at all, is known as the man who tried to smuggle a ciphered letter to his brother-in-law in besieged Boston and is believed to have been a paid informant for the British Commander, General Thomas Gage. But, on this day, Dr. Church was to deliver a speech that would solidify his position as one of the top Patriot leaders. Indeed, by April 1775, the three most prominent Boston Whigs were Adams, Warren, and Church; not John Hancock and certainly not the cantankerous, argumentative, and grumpy John Adams.

Benjamin Church, Jr. was born in Newport, R.I in August 1734, the son of Deacon (Benjamin Sr) and Hannah (Dyer) Church. The Churches were a prominent New England family who had came over on the Mayflower. The Rhode Island Churches were particularly prominent since they were the direct descendants of Col Benjamin Church, who was Dr. Church’s great-grandfather. Col Church is now little remembered but in late colonial times was still very famous for his exploits in King Phillip’s War, King William’s War, and Queen Anne’s War. King Phillip’s War (Phillip was the British name for the Wampanoaq sachem (chief), Metacomet, who led the Indian side in the war) was the single greatest calamity to occur in seventeenth-century New England. In little over a year of war, nearly half of the region’s towns were destroyed, its economy was all but ruined, and a substantial portion of the population was killed. More than half of New England’s towns were attacked by Indian warriors. Proportionately, it was one of the costliest wars in North American history. Col Church was responsible for the introduction of military units that melded colonials with frontier skills with allied Indians to carry out strikes against hostile Indian forces and settlements using “ranger like†tactics. King Phillip’s War ended soon after a company commanded by Church killed Metacomet. Church then went on to fight in two other wars conducting raids all over New England, even though it is reported that he weighed over 250 pounds. It was this Church who, as a newly married man, moved the family to Rhode island. It was his grandson, Benjamin Church, Sr., who moved the family back to Boston in 1740 where he had an auction stand on Newbury Street and served as a deacon at Dr. Mather Byles’ Hollis Street Church in Boston’s South End.

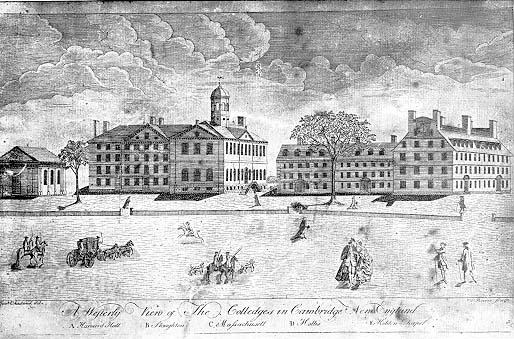

Benjamin Jr. graduated from Boston Latin School and like his father, graduated from Harvard (class of 1754) along with his classmate John Hancock. After graduation, Church studied medicine to include three years in London where he married Sarah Hill of Ross in Hertfordshire. Upon his return to Boston in 1759, Church established himself as a physician, surgeon and apothecary. Church widely advertised his skill at inoculation and won the appreciation of the town selectmen for his services to the poor during smallpox epidemics. Inoculation should not be confused with vaccination and is a much more involved and dangerous process. Patients prepared themselves for days beforehand and were often sick for weeks after. While Church was mastering his chosen profession, he returned to something in which he had been heavily involved in at Harvard- poetry. During Church’s college days, he and his fellow Harvard students engaged in writing poems concerned almost exclusively with satirizing Harvard personalities and events, a natural subject for their wit. The students recognized that satire was one of the principal literary modes by which they could compete for position within the community. While most of these poems can be considered juvenile and sophomoric, they were a great learning experience for those who wrote them. And Church’s efforts stand out for their viciousness, if not literary value.  But Church shrewdly understood his audience and because he learned and mastered the the techniques of satire while at Harvard, he was able to create a poetic voice that met the needs of his generation and use it to further his own ambitions. But Church also began to write serious poetry. In 1757, Church published “The Choiceâ€, a poem began while at Harvard that would prove to be the high point of Church’s poetic career and a poem which modern critics would label a landmark in the literature of colonial America. The poem is not suited to modern ears but it is important to note that in the poem Church was establishing an American style and confronting American issues.

Benjamin Jr. graduated from Boston Latin School and like his father, graduated from Harvard (class of 1754) along with his classmate John Hancock. After graduation, Church studied medicine to include three years in London where he married Sarah Hill of Ross in Hertfordshire. Upon his return to Boston in 1759, Church established himself as a physician, surgeon and apothecary. Church widely advertised his skill at inoculation and won the appreciation of the town selectmen for his services to the poor during smallpox epidemics. Inoculation should not be confused with vaccination and is a much more involved and dangerous process. Patients prepared themselves for days beforehand and were often sick for weeks after. While Church was mastering his chosen profession, he returned to something in which he had been heavily involved in at Harvard- poetry. During Church’s college days, he and his fellow Harvard students engaged in writing poems concerned almost exclusively with satirizing Harvard personalities and events, a natural subject for their wit. The students recognized that satire was one of the principal literary modes by which they could compete for position within the community. While most of these poems can be considered juvenile and sophomoric, they were a great learning experience for those who wrote them. And Church’s efforts stand out for their viciousness, if not literary value.  But Church shrewdly understood his audience and because he learned and mastered the the techniques of satire while at Harvard, he was able to create a poetic voice that met the needs of his generation and use it to further his own ambitions. But Church also began to write serious poetry. In 1757, Church published “The Choiceâ€, a poem began while at Harvard that would prove to be the high point of Church’s poetic career and a poem which modern critics would label a landmark in the literature of colonial America. The poem is not suited to modern ears but it is important to note that in the poem Church was establishing an American style and confronting American issues.

Following publication of “The Choiceâ€, his trip to London and return, Church settled down in Boston with his new wife and seems to have been content to practice medicine. Buoyed by the success of “The Choice†and the reception it received in Boston, Church continued to write more verse; although, for some reason, none of it was published for several years. Church did contribute two poems in praise of George III’s upcoming accession to the British throne that were finally published in 1763; two poems Church would regret composing. By 1764, Church had established himself as one of Boston’s leading physicians who, along with Dr. Joseph Warren and others, battled the smallpox epidemic that swept through Boston in the summer of 1764. It was the Stamp Act that would propel Church into becoming the leading satirist and polemicist of the Whig cause.

In 1765 Church published his his finest piece of political propaganda. Although not as highly visible as some of his later pieces, “Liberty and Property Vindicated and the St—pm-n Burntâ€, published first in Connecticut and reprinted in Boston, was a masterpiece of irony. But despite its merit, the poem did not have the desired effect. While more educated readers had little difficulty in understanding it, the majority of the audience for whom it was intended had difficulty in understanding the irony.  Therefore, it was not as successful for Church as some of his later political poems where the antagonists were clearly identifiable and the narrator was clearly the satirist. In a series of poems that followed well into the 1770s, Church satirized and blistered the Royal Governor, Tory ministers, and many other individuals. His attacks on the Royal Governor, Francis Bernard were especially vicious and made Church the darling polemicist of the Whigs and a man who was hated and cursed by the Tories.

But there was another side to Church’s poetry. In Bickerstaff’s “Boston Almanac for the year 1769â€, Church seems to be foreshadowing Walt Whitman with the following:

Lo! I warming westward on rejoicing suns,

See colonies extend; the calm retreat

Of undeserved distress; the better home

Of those whom bigots chase from foreign lands:

Not built on rapine, servitude and woe,

And in their turn some petty tyrants prey:

But bound by social Freedom, firm they rise. —

Rushing to light a race of men behold.

And so a crowd filled the Old South Meeting House; stuffed it so full that John Hancock, who was serving as moderator, had to enter the church through a side window in order to get to the platform. They knew that they were about to be addressed by perhaps the quickest wit in all of Boston, if not North America on an occasion that still stirred the hearts and minds of all Bostonians. But what was the political situation as Benjamin Church stood to address his audience of perhaps 5,000 men women and children? The fallout from the Boston Massacre had forced the British to remove all of her troops from Boston proper, although the 14th Regiment was only three miles away and could be reinforced with other regiments and reoccupy the town. Trade had exploded with the collapse of the non-importation agreement and merchants and shopkeepers stocked their shelves with all kinds of goods. The Whigs dominated Boston and held majorities in the House and Council but the Tories still controlled the executive and judicial branches. Most Bostonians grudgingly accepted the status quo and just wanted to get on with their lives. A few, such as Samuel Adams, still dreamed of independence but knew that they didn’t have enough support either in Boston or throughout the colonies for any chance of success. John Adams had “retired†to Braintree and John Hancock was flirting with the Tories. It was important to Samuel Adams and the hardcore Whigs that they keep their cause alive. In late 1772, Britain decided to remove the colonial assembly’s right to pay the salaries of the governor and the judges thus removing any power it had over Royal officials. A group of Boston citizens led by Samuel Adams formed a citizens’ committee to oppose the action. The committee compiled a three-part document soon known as the “Boston Pamphlet†and distributed it throughout the colony. The document (1) asserted the colonists’ rights as men under natural law, as Christians under God’s law in the New Testament, and as British subjects under the British constitution; (2) listed twelve violations of those rights by Britain; and (3) invited response from other Massachusetts towns. ( Those who seem to believe that the Declaration of independence was pure Jefferson should read the Boston Pamphlet.) Soon over one hundred new town “committees of correspondence†had been formed in Massachusetts. Benjamin Church was responsible for coordinating this pamphlet with other towns and was designated to start a correspondence with the radical James Wilkes in England, an indication of the trust and prominence Church now had. Even the day before the speech, Church was a member of a committee that met with Governor Hutchinson to discuss the salary issue.

And so a crowd filled the Old South Meeting House; stuffed it so full that John Hancock, who was serving as moderator, had to enter the church through a side window in order to get to the platform. They knew that they were about to be addressed by perhaps the quickest wit in all of Boston, if not North America on an occasion that still stirred the hearts and minds of all Bostonians. But what was the political situation as Benjamin Church stood to address his audience of perhaps 5,000 men women and children? The fallout from the Boston Massacre had forced the British to remove all of her troops from Boston proper, although the 14th Regiment was only three miles away and could be reinforced with other regiments and reoccupy the town. Trade had exploded with the collapse of the non-importation agreement and merchants and shopkeepers stocked their shelves with all kinds of goods. The Whigs dominated Boston and held majorities in the House and Council but the Tories still controlled the executive and judicial branches. Most Bostonians grudgingly accepted the status quo and just wanted to get on with their lives. A few, such as Samuel Adams, still dreamed of independence but knew that they didn’t have enough support either in Boston or throughout the colonies for any chance of success. John Adams had “retired†to Braintree and John Hancock was flirting with the Tories. It was important to Samuel Adams and the hardcore Whigs that they keep their cause alive. In late 1772, Britain decided to remove the colonial assembly’s right to pay the salaries of the governor and the judges thus removing any power it had over Royal officials. A group of Boston citizens led by Samuel Adams formed a citizens’ committee to oppose the action. The committee compiled a three-part document soon known as the “Boston Pamphlet†and distributed it throughout the colony. The document (1) asserted the colonists’ rights as men under natural law, as Christians under God’s law in the New Testament, and as British subjects under the British constitution; (2) listed twelve violations of those rights by Britain; and (3) invited response from other Massachusetts towns. ( Those who seem to believe that the Declaration of independence was pure Jefferson should read the Boston Pamphlet.) Soon over one hundred new town “committees of correspondence†had been formed in Massachusetts. Benjamin Church was responsible for coordinating this pamphlet with other towns and was designated to start a correspondence with the radical James Wilkes in England, an indication of the trust and prominence Church now had. Even the day before the speech, Church was a member of a committee that met with Governor Hutchinson to discuss the salary issue.

But on this afternoon Benjamin Church, Jr. proceeded with all the vigor of a man who knew that he was giving the most important speech of his career. Although Church’s oration was presented in an impassioned manner in the tradition of the classical oration, his performance is an emotional outburst that made the piece a popular one and led to its publication.

We are not to obey a Prince, ruling above the limits of the power entrusted to him; for the Common-wealth by constituting a head does not deprive itself of the power of its own preservation. Government or Magistracy whether supreme or subordinate is a mere human ordinance, and the laws of every nation are the measure of magistratical power; and Kings, the servants of the state, when they degenerate into tyrants, forfeit their right to government. (emphasis added)….

To enjoy life as becomes rational creatures, to possess our souls with pleasure and satisfaction, we must be careful to maintain that inestimable blessing, Liberty. By liberty I would understand, the happiness of living under laws of our own making, by our personal consent, or that of our representatives….

The constitution of England, I revere to a degree of idolatry; but my attachment is to the common weal; the magistrate will ever command my respect, by the integrity and wisdom of his administrations….

As in every government there must exist a power superior to the laws, viz. the power that makes those laws, and from which they derive their authority; therefore the liberty of the people is exactly proportioned to the share the body of the people have in the legislature; and the check placed in the constitution on the executive power. That state only is free, where the people are governed by laws which they have a share in making; and that country is totally enslaved where one single law can be made or repealed without the interposition or consent of the people….

But remember my Brethren! When a people have once sold their liberties, it is no act of extraordinary generosity, to throw their lives and properties into the bargain, for they are poor indeed when enjoyed at the mercy of a master….

Where laws are framed and assessments laid without a legal representation, and obedience to such acts urged by force, the despairing people robbed of every constitutional means of redress, and that people, brave and virtuous, must become the admiration of ages, should they not appeal to those powers, which the immutable laws of nature have lent to all mankind. Fear is a slender tye of subjection, we detest those whom we fear, and with the destruction to those we detest; but humanity, uprightness and good faith, with an apparent watchfulness for the welfare of the people, constitute the permanency, and are the firmest support of the sovereign’s authority; for when violence is opposed to reason and justice, courage never wants an arm for its defence….

But let us not forget the distressing occasion of this anniversary: The sullen ghosts of murdered fellow-citizens, haunt my imagination “and harrow up my soul,”* methinks the tainted air is hung with the dews of death, while Ate’ hot from hell, cries havock, and lets slip the dogs of war.** Hark! the wan tenants of the grave still shriek for vengeance on their remorseless butchers: Forgive us heaven! Should we mingle involuntary execrations, while hovering in idea over the guiltless dead.

The speech ended to thunderous applause as Church ended with his most fiery rhetoric:

The whole soul clamors for arms, and is on fire to attack the brutal banditti; we fly agonizing to the horrid aceldama (field of blood – refers to the field Judas Iscariot purchased for betraying Jesus Christ) we gaze on the mangled corpses of our brethren and grinning furies, gloating o’er their carnage, the hostile attitude of the miscreant murders, redoubles our resentment, and makes revenge a virtue.

By heaven they die! Thus nature spoke, and the swollen heart leap’d to execute the dreadful purpose; dire was the interval of rage, fierce was the conflict of the soul. In that important hour, did not the stalking ghosts of our stern forefathers, point us to bloody deeds of vengeance? Did not the consideration of our expiring liberties, impel us to remorseless havock? But hark! The guardian God of New England issues his awful mandate. “Peace, be Still.” Hushed was the bursting war, the lowering tempest frowned its rage away. Confidence in that God, beneath whose wing we shelter all our cares, that blessed confidence released the dastard, the cowering prey. With haughty scorn we refused to become their executioners, and nobly gave them to the wrath of heaven. But words can poorly paint the horrid scene. Defenceless, prostrate, bleeding countrymen — the piercing, agonizing groans –the mingled moan of weeping relatives and friends — these best can speak; to rouse the luke-warm into noble zeal, to fire the zealous into manly rage; against the foul oppression of quartering troops, in populous cities, in times of peace.

I will leave Dr. Church at this, his finest hour, but caution that there is so much more to his story. After the so-called Boston Tea Party, Church became even more prominent in the Patriot ranks, being elected to the Massachusetts Provisional Congress and member, and for a time, Chairman of the Committee of Safety, as important and sensitive a position as there was. Dr. Church would later be arrested by George Washington, tried, and incarcerated under dreadful conditions.  Eventually he would be sent into exile and presumably drowned at sea as the ship carrying him into exile sunk.  His wife and children would flee to England, losing everything they owned. A Boston mob would burn his house and all of his papers. What precisely he was doing in allegedly collaborating with General Gage is a fascinating complex story which I am in the process of telling.

What we know about Church has to be gleaned from the letters and writings of other individuals since only a handful of his letters survive and, of course, no notebooks, accounts or ledgers. Indeed, we do not even know what Dr. Church looked like. A portrait of him that is floating around the internet, and is allegedly an official US Army portrait, I have shown to have been drawn over a century after his death and is based only on the artist’s imagination. The only physical description we have of him is that of his opponents who called him “the lean apothecary†and “the cadaver.â€Â I have had a decades long interest in Church and the period in which he lived. Those who may have a similar interest I invite to check out a blog I have devoted to Dr Church and this period in pre revolutionary Boston at: http://drbenjaminchurchjr.blogspot.com

Edward Witek writes for the blog Dr. Benjamin Church Jr., which presents original research concerning Dr Church and his role in the American Revolution.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

That helps with my assignment on Church. Thanks!

[Reply]

Great! You should also check out Mr. Witek’s blog Dr. Benjamin Church Jr. for lots more information on Church.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment