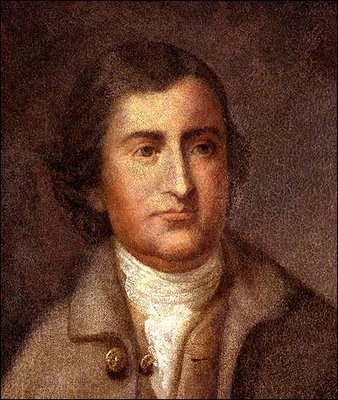

James Madison—Father of the Constitution?

In his later years, James Madison protested being called the Father of the Constitution. He said the document was not “the off-spring of a single brain.â€Â Our Constitution was actually the off-spring of fifty-five brains, although none as potent as Madison’s. A few historians have denigrated Madison’s informal title, saying he had merely outlived the other Founding Fathers and his convention notes gave him more credit than he would have received from an impartial observer. These critics also point out that the final Constitution diverted appreciably from the Virginia Plan that Madison supported as the correct governmental system.

In his later years, James Madison protested being called the Father of the Constitution. He said the document was not “the off-spring of a single brain.â€Â Our Constitution was actually the off-spring of fifty-five brains, although none as potent as Madison’s. A few historians have denigrated Madison’s informal title, saying he had merely outlived the other Founding Fathers and his convention notes gave him more credit than he would have received from an impartial observer. These critics also point out that the final Constitution diverted appreciably from the Virginia Plan that Madison supported as the correct governmental system.

We disagree. James Madison was arguably the most important Founder before, during, and after the Federal Convention of 1787.

Before the Constitutional Convention

In 1786, the country was at peace, but struggling. Congress called for a convention at Annapolis to offer amendments to the Articles of Confederation, but the meeting failed due to a lack of a quorum. James Madison and Alexander Hamilton made a pact to promote another convention for the following year in Philadelphia.

Immediately, Madison committed himself to making the Philadelphia convention successful. He renewed his study of historical republics, and the writings of government philosophers. He started corresponding with academics, clergy, and his fellow Founders. He not only was a major architect of the Virginia Plan, he worked ceaselessly to build a coalition of big states that could push the plan through the convention. Perhaps most important, he worked with Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson to convince George Washington to attend. Madison knew Washington’s Revolutionary renown would draw enough delegates to guarantee a quorum of the states.

With everything in ready, James Madison arrived in Philadelphia two weeks prior to the scheduled start of the convention—a month before the actual start.

During the Constitutional Convention

The Virginia Plan was presented by Edmund Randolph, the governor of Virginia, but everyone knew that it was Madison’s plan. He attended every session, and took the floor more than one hundred and fifty times, third after Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson. He attended every session, and sat in the front of the room so he could take extensive notes of all the deliberations. Madison also frequently influenced debate with speeches on first principles and theories of government. Toward the end of the convention, Madison sat on all the important committees that consolidated the prior four month’s deliberations and votes.

The Virginia Plan was presented by Edmund Randolph, the governor of Virginia, but everyone knew that it was Madison’s plan. He attended every session, and took the floor more than one hundred and fifty times, third after Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson. He attended every session, and sat in the front of the room so he could take extensive notes of all the deliberations. Madison also frequently influenced debate with speeches on first principles and theories of government. Toward the end of the convention, Madison sat on all the important committees that consolidated the prior four month’s deliberations and votes.

During the convention, Madison changed many minds, but he also changed his mind on many details of the government design. He felt confident in the results, but he knew their work was going to be an academic exercise unless he could get the people to adopt it.

After the Constitutional Convention

Madison played a key part in guiding the Constitution through the Continental Congress, a prerequisite to getting it out to the people for ratification. Once this was accomplished, they needed nine states to ratify, but New York and Virginia were absolutely crucial. These two prosperous states would split the country geographically if they decided to go their own way. Madison, pretending to be a New Yorker, joined Hamilton and Jay in writing the Federalist Papers, which were the op-ed opinion pieces of the day. Next, he raced home to Virginia to lead the Federalist charge in the Virginia Ratification convention. Taking on Patrick Henry, reputedly the best speaker in the country, Madison led his caucus to victory—albeit with some political shenanigans by George Washington.

But he wasn’t done. Ratification victory in several states depended on a promise to add a Bill of Rights to the Constitution. Madison was the one to lead the First Congress to make good on this promise—resulting in his second moniker, Father of the Bill of Rights.

James Madison, Father of the Constitution

For three years, Madison dedicated almost every waking moment to the study of governments, designing a system that would last, and securing the approval for our Constitution. George Washington may have once again played the role of the indispensable man, but he and the rest of the delegates depended on the intellect and prodigious work of little Madison.

What would he think today? It’s inappropriate to put thoughts into any man’s head, especially James Madison’s, but he would surely be appalled at the blurring of the separation of powers. His mantra was separation of powers, checks and balances, and the ultimate authority of the people. The three federal branches have made it a habit to encroach on each other while trampling the 10th Amendment. If he were here today, he’d probably tell everyone to get back to their appropriate corner.

James D. Best is the author of Tempest at Dawn, a novel about the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

Excellent post! Madison was indeed key.

[Reply]

James Madison certainly worked hard for what he believed in.

He had an admirable intellect, studious habits, and the ability to influence others by clearly articulating his ideas.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment