Nullification: An Early Argument

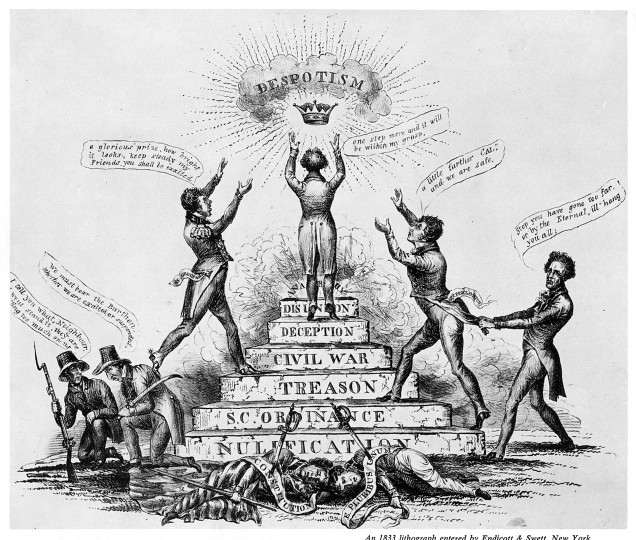

Do the states have the power, or indeed the obligation, to nullify federal laws, if those laws are unconstitutional. We won’t presume to answer that question here. However, we will examine some of the arguments raised during the Nullification Crisis of 1832.

Some background is probably in order.

The debate centered around President Andrew Jackson’s Tariff of 1832. The South, and South Carolina in particular, saw this tariff as a nothing less than a means of transferring wealth to the northern states at the expense of the southern states. The tariff ensured that the prices for northern finished goods would remain artificially high by protecting them from foreign competition. At the same time, raw cotton enjoyed no such protection, and was sold at market value.

The debate centered around President Andrew Jackson’s Tariff of 1832. The South, and South Carolina in particular, saw this tariff as a nothing less than a means of transferring wealth to the northern states at the expense of the southern states. The tariff ensured that the prices for northern finished goods would remain artificially high by protecting them from foreign competition. At the same time, raw cotton enjoyed no such protection, and was sold at market value.

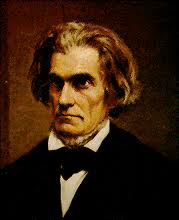

Interestingly enough, the debate pitted the Vice President, John C. Calhoun, against President Jackson, as the leaders of the opposing sides. Calhoun resigned as Vice President to take up his argument in the Senate, where South Carolina returned him.

Calhoun championed the notion of states’ rights and maintained that the unconstitutional federal laws could and should be “nullified” by the states as a legitimate means of defending not only their rights, but also in protection of the Constitution itself and the people.  In support of his argument, Calhoun referenced the work of James Madison and Thomas Jefferson in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which pertained to the obligation of the states to ignore the odious Alien and Sedition Acts, enacted during the Federalist administration of John Adams. The salient portion:

RESOLVED, That this commonwealth considers the federal union, upon the terms and for the purposes specified in the late compact, as conducive to the liberty and happiness of the several states: That it does now unequivocally declare its attachment to the Union, and to that compact, agreeable to its obvious and real intention, and will be among the last to seek its dissolution: That if those who administer the general government be permitted to transgress the limits fixed by that compact, by a total disregard to the special delegations of power therein contained, annihilation of the state governments, and the erection upon their ruins, of a general consolidated government, will be the inevitable consequence: That the principle and construction contended for by sundry of the state legislatures, that the general government is the exclusive judge of the extent of the powers delegated to it, stop nothing short of despotism; since the discretion of those who administer the government, and not the constitution, would be the measure of their powers: That the several states who formed that instrument, being sovereign and independent, have the unquestionable right to judge of its infraction; and that a nullification, by those sovereignties, of all unauthorized acts done under colour of that instrument, is the rightful remedy: That this commonwealth does upon the most deliberate reconsideration declare, that the said alien and sedition laws, are in their opinion, palpable violations of the said constitution; and however cheerfully it may be disposed to surrender its opinion to a majority of its sister states in matters of ordinary or doubtful policy; yet, in momentous regulations like the present, which so vitally wound the best rights of the citizen, it would consider a silent acquiescence as highly criminal: That although this commonwealth as a party to the federal compact; will bow to the laws of the Union, yet it does at the same time declare, that it will not now, nor ever hereafter, cease to oppose in a constitutional manner, every attempt from what quarter soever offered, to violate that compact:

AND FINALLY, in order that no pretexts or arguments may be drawn from a supposed acquiescence on the part of this commonwealth in the constitutionality of those laws, and be thereby used as precedents for similar future violations of federal compact; this commonwealth does now enter against them, its SOLEMN PROTEST.

In 1832, Calhoun addressed a convention held in South Carolina, which declared the tariff to be null and void. This doctrine of “interposition” as built on by Calhoun, suggested that the states, as sovereign entities, were obligated to check the usurpation of power by the federal government.

… the Constitution of the United States is a compact between the people of the several States, constituting free, independent, and sovereign communities;—that the Government it created was formed and appointed to execute, according to the provisions of the instrument, the powers therein granted, as the joint agent of the several States; that all its acts, transcending these powers, are simply and of themselves, null and void, and that in case of such infractions, it is the right of the States, in their sovereign capacity, each acting for itself and its citizens, in like manner as they adopted the Constitution, to judge thereof in the last resort, and to adopt such measures—not inconsistent with the compact—as may be deemed fit…

Calhoun argued that ratification of the Constitution did not indicate an abdication of the sovereign rights and responsibilities of the states. Although the states were bound to abide and submit to those powers that they had delegated to federal government, they were equally bound to resist encroachment of the powers reserved to the states or the people.

But the obligation of a State to resist the encroachments of the Government on the reserved powers, is not limited simply to the discharge of its federal duties. We hold that it embraces another, if possible, more sacred ;—that of protecting its citizens, derived from their original sovereign character, viewed in their separate relations. There are none of the duties of a State of higher obligation. It is, indeed, the primitive duty,—preceding all others, and in its nature paramount to them all; and so essential to the existence of a State, that she cannot neglect or abandon it, without forfeiting all just claims to the allegiance of her citizens, and with it, her sovereignty itself.

…

Nor is it less true, that the General Government, created in order to preserve the rights placed under the joint protection of the States, and which, when restricted to its proper sphere, is calculated to afford them the most perfect security, may become, when not so restricted, the most dangerous enemy to the rights of their citizens, including those reserved under the immediate guardianship of the States respectively, as well as those under their joint protection; and thus, the original and inherent obligation of the States to protect their citizens, is united with that which they have contracted to support the Constitution; thereby rendering it the most sacred of all their duties to watch over and resist the encroachments of the Government; —and on the faithful performance of which, we solemnly believe the duration of the Constitution and the liberty and happiness of the country depend.

Calhoun stresses, that far from wanting to harm the union, South Carolina’s nullification of the tariff indicated a desire to cherish and protect it.

In taking the stand which she has, the State has been solely influenced by a conscientious sense of duty to her citizens, and to the Constitution, without the slightest feeling of hostility towards the interests of any section of the country, or the remotest view to revolution,—or wish to terminate her connection with the Union ;—to which she is now, as she ever has been, devotedly attached. Her object is, not to destroy, but to restore and preserve: and, in asserting her right to defend her reserved powers, she disclaims all pretension to control or interfere with the action of the Government within its proper sphere,—or to resume any powers that she has delegated to the Government, or conceded to the confederated States. She simply claims the right of exercising the powers which, in adopting the Constitution, she reserved to herself; —and among them,—the most important and essential of all,—the right to judge, in the last resort, of the extent of her reserved powers,—a right never delegated nor surrendered, —nor, indeed, could be, while the State retains her sovereignty. That it has not been, we appeal with confidence to the Constitution itself, which contains not a single grant that, on a fair construction, can be held to comprehend the power. If to this we add the fact, which the Journals of the Convention abundantly establish, that reiterated, but unsuccessful attempts were made, in every stage of its proceedings, to divest the States of the power in question, by conferring on the General Government the right to annul such acts of the States, as it might deem to be repugnant to the Constitution, and the corresponding right to coerce their obedience,— we have the highest proof of which the subject is susceptible, that the power in question was not delegated, but reserved to the States. To suppose that a State, in exercising a power so unquestionable, resists the Union, would be a fundamental and dangerous error,—originating in a radical misconception of the nature of our political institutions. The Government is neither the Union, nor its representative, except as an agent to execute its powers. The States themselves, in their confederated character, represent the authority of the Union; and, acting in the manner prescrihed by the Constitution, through the concurring voice of three fourths of their number, have the right to enlarge or diminish, at pleasure, the powers of the Government,—and to amend, alter, or even abolish the Constitution, and, with it, the Government itself. Correctly understood, it is not the State that interposes to arrest an unconstitutional act,—but the Government that passed it, which resists the authority of the Union. The Government has not the right to add a particle to its powers; and to assume, on its part, the excrcise of a power not granted, is plainly to oppose the confederated authority of the States, to which the right of granting powers exclusively belongs ;—and, in so doing, the Union itself, which they represent. On the contrary, a State, as a member of the body in which the authority of the Union resides,—in arresting an unconstitutional act of the Government, within its limits,—so far from opposing, in reality supports the Union, and that in the only effectual mode in which it can be done in such cases. To divest the States of this right, would be, in effect, to give to the Government that authority over the Constitution, which belongs to them exclusively; and which can only be preserved to them, by leaving to each State,—as the Constitution has done,—to watch over and defend its reserved powers against the encroachments of the Government,—and in performing which, it acts, at the same time, as a faithful and vigilant sentinel over the confederate powers of the States.

The issue was diffused by the compromise tariff of 1833, brokered by Henry Clay. Consequently, nullification has never been subjected to adjudication by the courts and still has some adherents today.  Calhoun’s point was that the creation could not be greater than its creator. Since the federal government was delegated only certain powers by the States, and since the Constitution specifies the only method for changing these powers – 3/4’s of the states – in his view the federal government was but a creature of the states’ making and subject to their ultimate authority.

Others, however, didn’t see things as Calhoun did. Instead they viewed the concept of nullification as deadly to the Constitution and Union.

Regardless of the validity or viability of nullification, when reading through Calhoun’s arguments, one has to wonder how much sovereignty the states do retain if the federal government is free to set the limits of its own power at its discretion.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

1 comment

AWESOME!! article. we could use your material on our web site. check us out.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment