Private Hosea Rogers

Some years ago, I was asked by a friend from New Jersey if I would go to the National Archives and review a Revolutionary War Pension Application for a soldier from King George County of the Northern Neck of Virginia since his wife was a direct descendant of this soldier. I readily agreed, but after reading the application, I thought I would go a little further and try and trace this soldier’s movements during the Revolutionary War. Unlike the Civil War where detailed regimental histories proliferate, the Revolutionary War has had very little published at the regimental level and our knowledge of the actions at company level and lower are quite limited. There are several reasons for this. One is that a large percentage of the soldiers in the Revolutionary War were barely literate so that there is not a large treasure chest of letters and diaries for an historian to scour. This lack of documentation has not allowed historians to concentrate as fully on the individual enlisted soldiers of the Continental Army as they deserve. We know that there were bloody footprints in the snow at Valley Forge, but we know very little of the men who left them there.

Some years ago, I was asked by a friend from New Jersey if I would go to the National Archives and review a Revolutionary War Pension Application for a soldier from King George County of the Northern Neck of Virginia since his wife was a direct descendant of this soldier. I readily agreed, but after reading the application, I thought I would go a little further and try and trace this soldier’s movements during the Revolutionary War. Unlike the Civil War where detailed regimental histories proliferate, the Revolutionary War has had very little published at the regimental level and our knowledge of the actions at company level and lower are quite limited. There are several reasons for this. One is that a large percentage of the soldiers in the Revolutionary War were barely literate so that there is not a large treasure chest of letters and diaries for an historian to scour. This lack of documentation has not allowed historians to concentrate as fully on the individual enlisted soldiers of the Continental Army as they deserve. We know that there were bloody footprints in the snow at Valley Forge, but we know very little of the men who left them there.

The definitive study on the composition of the rank and file in the Virginia Regiments that served in the Revolutionary War was conducted by John Sellars of the Library of Congress. He conducted an analysis of the Revolutionary War Pension Application Files for all those who had enlisted in the Virginia regiments. Basically, they were young white males between the ages of 16 and 25, the sons of poor farmers and laborers. Allowing for error, Sellars determined that 90% of all soldiers were under 25 years of age when they entered the war. The median age of new recruits was only 20, and 21 recruits were mere boys, 14 or 15 years old. Sixteen was the minimum legal age for service in the Continental Army or the Virginia Militia; but recruiting officers, under pressure to enlist men for 15 regiments without the aid of a draft bill which the Virginia Assembly refused to pass until the war was almost half over, often winked at such restrictions. In 1775 and 1776, Virginia officers were also in competition with recruiters from South Carolina and Georgia. Frequently new recruits in the 14-19 year category entered the military as substitutes, both paid and voluntary. Older men were more likely to have enough money to hire substitutes. If a substitute fought voluntarily, it was most often for the benefit of a father who was needed at home or for an older married brother.

If the soldiers surveyed are grouped by year of enlistment, the average age does not vary year by year more than two percentage points. The preponderance of Virginia men in the army in 1781 continues to be in the 14-19 age bracket, as at the beginning of the war. This suggests that there was a high turnover rate among the Virginia troops, both in the militia and the regular line.

From the style of writing on their pension applications and the number of signatures that appear in the form of an “Xâ€, it is a safe bet that most non-commissioned officers and privates had little or no education.

Studies have indicated that there were approximately 45,000 Virginians, 400 of whom resided in King George County, eligible for military service in the colony in 1776.

And with that background, here is one Virginia private’s story, or as much as can be gleaned.

On August 3, 1820, Hosea Rogers of King George County Virginia appeared in District Court to furnish an affidavit concerning his service in the Revolutionary War in order to obtain a pension authorized by Congress. The sixty-one year old, father of three, was described in the affidavit as “a man of slender education, so much so that he sometimes has to hire some person to do the writing which it is necessary for him to do so in virtue of his office of constable.â€Â Orally, Rogers advised the court that in the fall of 1775, he had enlisted in the Minuteman Company (yes there were Minutemen Companies in Virginia) under Capt. Taliafero and that he had served for 11 days. On 15 February 1776, Rogers enlisted in Capt. Wallace’s Company in the 3rd Virginia for two years and he advised the court that he had participated in the Battle of Harlem Heights, “York Islandâ€, White Plains, Germantown, Piscataway in the neighborhood of Brunswick, and “many other skirmishesâ€. In addition, in 1781, Rogers served a tour of duty at the siege of “York†(Yorktown), on the Gloucester side of the river. In conclusion, Rogers stated that he almost lost sight of one eye due to smallpox, which he had contracted while in service.

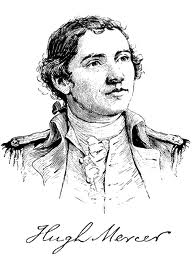

The Third Virginia Regiment of Foot, which included Capt. Wallace’s company (The Fifth), was an elite Virginia unit whose officers were: Colonel Hugh Mercer, a very close personal friend of George Washington, quickly promoted to Brigadier General; George Weedon, Lt Colonel, a tavern keeper in Fredericksburg and another friend of Washington: and, Major Thomas Marshall – a boyhood and life long friend of George Washington and father of future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall. In December 1775, at the request of George Washington, the 3rd Virginia was incorporated into the Continental Army. Using contemporary letters and diaries I detailed the movements, or as much as can be definitively established, of the Fifth Company of the 3rd Virginia for my friend. These are too extensive to detail here but suffice it to say that Private Rogers saw a great deal of action in the two years of his enlistment. We cannot know just what type of soldier he was or how fierce the action he personally saw; but that list of battles and skirmishes he listed in his pension application certainly is impressive. And Rogers would be one of those who would have stood by Washington during the darkest days of the War in December, 1776 when “Washington Crossed the Delaware.â€Â Rogers makes no mention of the Battle of Trenton in December 1776 yet it was the Third Virginia who had the honor to be the first to charge the Hessians down King and Queen Street. Because the 3rd was providing guard duty for the Hessians captured at Trenton, it missed the battle of Princeton in January 1777 and that would explain Rogers’ omission of that fight.

The Third Virginia Regiment of Foot, which included Capt. Wallace’s company (The Fifth), was an elite Virginia unit whose officers were: Colonel Hugh Mercer, a very close personal friend of George Washington, quickly promoted to Brigadier General; George Weedon, Lt Colonel, a tavern keeper in Fredericksburg and another friend of Washington: and, Major Thomas Marshall – a boyhood and life long friend of George Washington and father of future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall. In December 1775, at the request of George Washington, the 3rd Virginia was incorporated into the Continental Army. Using contemporary letters and diaries I detailed the movements, or as much as can be definitively established, of the Fifth Company of the 3rd Virginia for my friend. These are too extensive to detail here but suffice it to say that Private Rogers saw a great deal of action in the two years of his enlistment. We cannot know just what type of soldier he was or how fierce the action he personally saw; but that list of battles and skirmishes he listed in his pension application certainly is impressive. And Rogers would be one of those who would have stood by Washington during the darkest days of the War in December, 1776 when “Washington Crossed the Delaware.â€Â Rogers makes no mention of the Battle of Trenton in December 1776 yet it was the Third Virginia who had the honor to be the first to charge the Hessians down King and Queen Street. Because the 3rd was providing guard duty for the Hessians captured at Trenton, it missed the battle of Princeton in January 1777 and that would explain Rogers’ omission of that fight.

Rogers did winter at Morristown and it was probably during the winter of 1776-1777 that he contracted smallpox. In a letter dated in May 1777, George Weedon mentions that the Virginians were now quite healthy and “our men happily over the smallpox.â€Â Although the Virginia soldiers shared in the horrors of Valley Forge, as a group they were lucky. The terms of as many as half of the NCOs and enlisted soldiers in the Virginia Line would have expired before the next campaign, and to encourage re-enlistments, Washington granted them an early discharge. Starting on January 21, 1778, the older veterans left the army, literally in companies. Near the end of February, more than 1,350 men had returned to their homes and over 400 were expected to follow. On February 15, 1776, after two years of extreme hardship, Rogers received his discharge. He would have been given 16 shillings in expense money for what was listed as a 240 mile trip home – on foot. But like the other Virginians, Rogers would have to relinquish his blanket since there were not enough to go around for the men who remained. It must have been a cold trip home.

Rogers did winter at Morristown and it was probably during the winter of 1776-1777 that he contracted smallpox. In a letter dated in May 1777, George Weedon mentions that the Virginians were now quite healthy and “our men happily over the smallpox.â€Â Although the Virginia soldiers shared in the horrors of Valley Forge, as a group they were lucky. The terms of as many as half of the NCOs and enlisted soldiers in the Virginia Line would have expired before the next campaign, and to encourage re-enlistments, Washington granted them an early discharge. Starting on January 21, 1778, the older veterans left the army, literally in companies. Near the end of February, more than 1,350 men had returned to their homes and over 400 were expected to follow. On February 15, 1776, after two years of extreme hardship, Rogers received his discharge. He would have been given 16 shillings in expense money for what was listed as a 240 mile trip home – on foot. But like the other Virginians, Rogers would have to relinquish his blanket since there were not enough to go around for the men who remained. It must have been a cold trip home.

I thought that the Hosea Rogers story would end with his service at Yorktown and his long life as a constable and farmer in the rural Northern Neck of Virginia. But Rogers’ story held one final surprise. Rogers received an $8 a month pension and died at the age of 79 in January 1838. In his will, he left various bequests of $50 to his children and grandchildren and left his land, “Negroes”, property and stock to his daughter Polly. He was not a very wealthy man. In addition, slave owner Hosea Rogers requested his daughter “to return to Daingerfield Lewis a walking cane which was formerly the property of Gen. George Washington and which was given to me by said Lewis.â€Â I was stunned when I read that. Daingerfield Lewis, a large property owner and product of some of Virginia’s oldest and richest families, was the Great-nephew of George Washington and grandson of George’s beloved sister “Betty†( Elizabeth.) A gentleman’s canes were highly valued and symbolic possessions in late 18th century and early 19th century America. Washington alone made three specific bequests of his canes in his will, one of which was a gold cane given to him by Benjamin Franklin. It was a way for a gentleman to honor and respect someone in his will.

I thought that the Hosea Rogers story would end with his service at Yorktown and his long life as a constable and farmer in the rural Northern Neck of Virginia. But Rogers’ story held one final surprise. Rogers received an $8 a month pension and died at the age of 79 in January 1838. In his will, he left various bequests of $50 to his children and grandchildren and left his land, “Negroes”, property and stock to his daughter Polly. He was not a very wealthy man. In addition, slave owner Hosea Rogers requested his daughter “to return to Daingerfield Lewis a walking cane which was formerly the property of Gen. George Washington and which was given to me by said Lewis.â€Â I was stunned when I read that. Daingerfield Lewis, a large property owner and product of some of Virginia’s oldest and richest families, was the Great-nephew of George Washington and grandson of George’s beloved sister “Betty†( Elizabeth.) A gentleman’s canes were highly valued and symbolic possessions in late 18th century and early 19th century America. Washington alone made three specific bequests of his canes in his will, one of which was a gold cane given to him by Benjamin Franklin. It was a way for a gentleman to honor and respect someone in his will.

Daingerfield Lewis would have been about 14 years old when Washington died so it is entirely plausible that he received it directly from his Great Uncle.

Daingerfield Lewis certainly wasn’t a contemporary of Rogers, either in age (he was 27 years younger) or stature or, yes, class; yet, Lewis honored Rogers by giving him his Great-Uncle’s cane. Not just his Great-Uncle’s, but George Washington’s cane? It’s difficult to convey just what an honor this was back in the early 19th century.

There is no written family record or oral tradition, which would explain this. We can only wonder, a couple of centuries later, why this obscure, barely literate private of the 3rd Virginia was so honored.

Edward Witek writes for the blog Dr. Benjamin Church Jr., which presents original research concerning Dr Church and his role in the American Revolution.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

9 comments

This post was mentioned on the Motor City Times Blog.

Great article about early American history. I highly recommend it.

[Reply]

This is a part of my family that I have only recently begun researching. What a rich history!

[Reply]

Lorena Goeller Reply:

May 13th, 2011 at 12:15 pm

Yvonne, I’m a direct descendant of Hosea Rogers.

I have some completed family research. If I can be of any assistance, just send me an e-mail.

[Reply]

Laurie Brockman Reply:

September 21st, 2012 at 12:38 pm

Lorena,

I am wondering if you have any information on the John Davis and his family that married Hosea’s daughter Frances. I believe they are my ancestors.

[Reply]

Valeria Temple Reply:

September 27th, 2014 at 3:54 pm

Laurie, I am a descendant of Caroline Jackson Lee. A genealogy research of Miss Lee was done by George Harrison Sanford King, as ordered by the court. On page 79, Mr. King refers to: ROGERS’ ADMINISTRATORS VS DAVIS, King George County Chancery Suit Papers, Bundle March Term 1885.

If you do not have a copy of this book, it is located in the Library of Congress.

I found Mr. Witek story very interesting. Mr. Rogers daughter, Mary Coakley was married to James Lee Jr. His 2nd wife and they had four children. Nine total for him, with 5 from the first wife.

Maybe you already know all this, but I just found this article today. Valeria Ebert Temple gramx7@bbc.net

Lorena Goeller Reply:

March 6th, 2015 at 6:41 pm

Laurie, I know a little about the Davis family. John Davis married Frances Rogers (Hosea Roger’s daughter) & had a son named Jefferson Hosea Davis. John’s brother, James Davis, married Ann Hess & they had a daughter, Catherine Ann Davis. Catherine Ann Davis married Jefferson Hosea Davis, (her 1st cousin). Catherine Ann & Jefferson Hosea Davis had a daughter, Lorena, who was my great grandmother. If I can help with any further information, let me know.

elaine grigsby Reply:

March 5th, 2015 at 6:27 pm

Lorena I’d really like to get more information.

Thank you

Elaine

[Reply]

Lorena Goeller Reply:

March 6th, 2015 at 4:03 pm

Elaine, are you a descendant of Hosea Roger’s brother, William Rogers? His wife was a Grigsby. Let me know how I can help you.

Leave a Comment