Rediscovering Alexander Hamilton – The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

The folks at PBS were kind enough to send us a review copy of their new documentary on Alexander Hamilton. We had high hopes for this film given the quality and caliber of the Lafayette documentary we reviewed last year. Unfortunately, while twice as long, it wasn’t half as good.

The Good

The film’s writer and host, Richard Brookhiser, went to a great deal of trouble to interview a number of interesting and knowledgeable people, among them Ron Chernow, Jay Winik, and Sean Wilentz and several other historians. As always Chernow was insightful and engaging. Anyone who’s read his biography of Hamilton won’t come away from this documentary with anything new.  Of course, it’s not fair to compare a two hour film with the amount of information that can be packed  into an 800+ page tome. Nonetheless, it was interesting to see some of the places that Chernow referred to in his book (reviewed here). Brookhiser takes the viewer on a tour of the West Indies where Hamilton,  born the bastard son of a ne’erdowell member of the Scottish gentry, grew up. You see the prison in which Hamilton’s mother was held for adultery as well as Hamilton’s boyhood home. Brookhiser recounts Hamilton’s experience as a ship’s chandler clerk, the responsibility he was entrusted with at a young age, and the patronage he acquired from Kruger, the chandler and a Presbyterian minister named Knox. Both men recognized Hamilton’s intelligence and drive.

The Bad

The film gets off to an awkward start with Brookhiser’s interview of some women prison inmates whom he questions about what they think Hamilton’s mother felt and experienced during her incarceration. The interview seemed contrived and  pointless and  the questions embarrassingly inane.  If the purpose of this film was to explore Hamilton’s contributions to the nation and to connect him to issues that resonate today, the interview adds no value.  Unfortunately, it was the harbinger of worse interviews to come.

The Good

From the West Indies, Brookhiser takes us to New York and explains how the precocious Hamilton tried to finagle an abbreviated college program from Princeton’s Dean Witherspoon. Unsuccessful in his effort, he went instead to King’s college, now known as Columbia University, which features a Hamilton Hall and considers him their most famous alumnus.

By 1775, Hamilton was deeply involved in revolutionary activities, writing pamphlets and organizing a military unit off campus. Brookhiser points out that even today Columbia refuses to allow ROTC on their grounds.  Today’s off-campus ROTC calls itself the Hamilton Society in his honor.

The film provides a credible explanation of how Hamilton developed his opinion that a strong central government was critical, as well as his distrust of “the people.” It recounts his experience with a mob of “patriots” against whom he stands in defense of Miles Cooper, Princeton’s dean of King’s College. In spite of his diminutive stature, Hamilton  held the mob off  long enough for Cooper to escape out the back door of the building. The film covers Hamilton’s military career, beginning in 1776 when Hamilton’s military unit sees rearguard action with Washington’s troops as they flee New York. Hamilton crosses the Delaware with Washington, and it his artillery unit that controls the high ground at Trenton, a turning point in the war. Two weeks later, the patriot forces attack Princeton, where Witherspoon had rebuffed Hamilton’s proposal to become a student.

The film does a good job of  establishing the relationship  between Hamilton and Washington.  Washington, recognizing Hamilton’s brilliance, basically makes him his chief of staff. It was the beginning of one of the most successful collaborations of the Revolution and the years immediately following it.  Hamilton proves his mettle on the battlefield when he persuades Washington to  give him a long-sought-after military command. In 1781, at the siege of Yorktown, Hamilton is given the task of taking British redoubt no. 10. As one of the first through the barricades, Hamilton leads his men into a quick, but fierce and bloody battle of bayonets. Hamilton is with Washington at the surrender.

The film follows Hamilton’s post war  law career. He represents a good many loyalists in court cases pertaining to the Trespass Act. He argues successfully that people obeying a duly constituted law are entitled to its protection, regardless of how circumstances change perceptions later.  A nicely done, but too brief vignette is the partial  re-enactment of the case of Rutger vs. Wattington in front of a modern judge. This case is viewed by many as the source of the concept of “judicial review.” One of the “fundamentals” that Hamilton argued for was that Federal Law trumps State Law. This was another indication of Hamilton’s preference for a strong central government.

In spite of his successful law practice, Hamilton wasn’t done with politics.  He was one of three delegates from New York to the Constitutional Convention.  Brookhiser points out that Hamilton did not say much during the convention, except to argue at one point, for a lifetime tenure for the chief executive.  Although the secrecy of the proceedings was kept remarkably well, his political enemies never forgave him for his seeming support of an American monarchy.

After the Convention, Hamilton masterminded the writing of the Federalist papers with James Madison and John Jay.  There are  some very interesting sections about modern day applications of the Federalist papers, which are  given short shrift. One of these was a brief explanation of how Federalist arguments were used on both sides of a landmark case on the notion of granting habeus corpus to foreign nationals – e.g. non-US citizens alleged to be terrorists. There were also some brief discussions with Supreme Court Justice Scalia who made the point that it is not the Bill of Rights that makes the American Constitution exceptional, but the separation of powers. Unfortunately, it was not elaborated. Hamilton’s prolific pen and monumental writing of the bulk of the Federalist papers is also not given nearly enough attention. There was an interesting snippet where Brookhiser interviews a handwriting expert who posits that Hamilton couldn’t write as fast as his brain could form coherent paragraphs – and thus he often didn’t bother crossing T’s and dotting I’s.

Brookhiser does a reasonable job explaining Hamilton’s precedent setting financial policies as the first Secretary of the Treasury, with regard to assumption of the States’ debts and the charter of the first Bank of the United States. His interview with Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson is marginally interesting in its attempt to link the current with the past. He attempts to draw parallels between the financial bubble of 1792 and the housing bubble of today. The idea that New York in general and Wall Street in particular are monuments to Hamilton is well presented.

Hamilton’s notion of speculators was that they were a necessary and unavoidable component of a free market economy. Hamilton,  a city dweller who believed in mixed economies of commerce and agriculture, is contrasted with Jefferson and other Virginians who foresaw an agrarian utopia.

The film explores the differences between Hamilton and Jefferson regarding the Revolution in France and how  those differences defined the political parties led by them.  Jefferson’s republicans were apologists for the mobs in France, while the violence there quickly became anathema to Hamilton’s  Federalists.

The film portrays a heated argument  between Jefferson and Hamilton in one of Washington’s cabinet meetings about the proper course for the new country to take. Hamilton was triumphant, in that Washington would steer a neutral course, but Washington avoided use of the inflammatory word, neutral, in an attempt to mollify the French.

The film doesn’t elaborate on Hamilton’s integrity nor does it explore Washington’s influence in controlling Hamilton’s intemperance and egoism. Â It does explain that the famous Washington/Hamilton collaboration continued throughout Washington’s presidency – even after Hamilton resigned office. However, too little attention is paid to Hamilton’s behavior during the Adam’s administration.

At the end of the film, the viewer is shown an interesting quasi-re-enactment of the famous duel by descendants of Burr and Hamilton. Hamilton’s descendant looks remarkably like him!

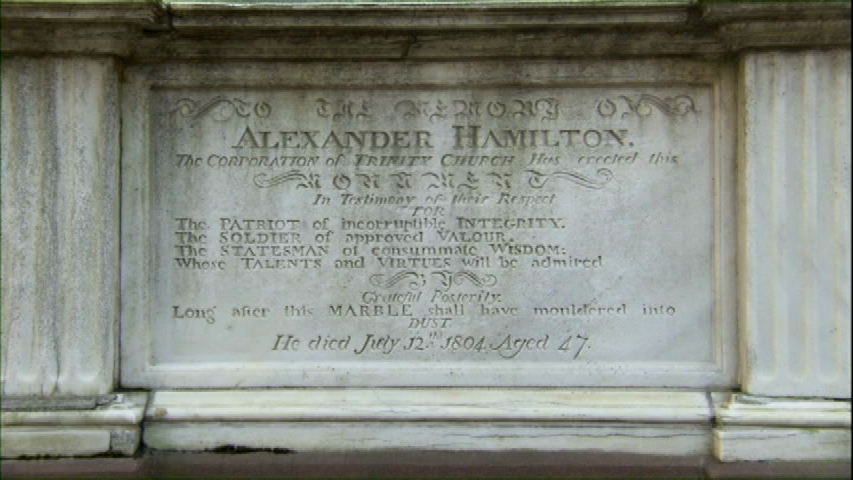

The film includes pictures of Trinity Church where Hamilton is buried. It  is only a few blocks away from the World Trade Center and his grave was covered with debris from the falling buildings. Because Hamilton founded the Coast Guard, it has become a tradition for all new chiefs to get their picture taken at his grave site in New York. It was the Coast guard that came in and cleaned up the debris that buried his tomb after 9/11.

The Bad

The film  tries too hard  to forge parallels between Hamilton’s time and today.  Brookhiser’s interview of Larry Flynt, ostensibly as a modern day example of the seamy press that publicized  the Maria Reynolds affair, was forced and awkward.  Even Flynt’s staff appear to struggle to find any sort of parallel with the present day. Why anyone would care what Larry Flynt has to say on anything of consequence, is beyond us.

The Ugly

The epitome of  inappropriate and contrived parallels was the prolonged interview with obese gang members in an attempt to link their concept of honor with the one that animated Hamilton in his duel with Aaron Burr. It struck this reviewer as ridiculous and a waste of valuable  time that could have been put to better use  elaborating on events and issues that were either  touched upon or neglected.  The  gangsters being interviewed didn’t know the first thing about Hamilton or Burr, let alone understand the concept of  18th Century honor.  Giving their opinions (not to mention their lifestyles) any  credence diminished the seriousness of the film.

Finally, ending with a rap solo exemplified the false premise that seemed to guide the making of the film. In their search for  a “third way” to  present  history,  the makers of the film seem to have mistaken innovation for relevance.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

6 comments

A rap solo?

[Reply]

Sounds like I’ll be skipping this show. My time would be better spent reading a real book.

I’m not sure if this is your error or the producers of the show, but Myles Cooper was President of King’s College (Columbia), not Princeton.

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

April 18th, 2011 at 7:50 pm

Michael, thanks, my error in writing the review.

[Reply]

If the 3 fat gang-bangers in the bottom pic know anything about honor, then I’m the King of Siam.

[Reply]

I’ve seen that rap before (on YouTube,) and though it’s a little weird to hear a rap about a Founding Father, it’s kind of interesting, and written from the heart. (And I say this as a person who can’t stand rap music.) I had a friend of mine who knew only a little about Hamilton watch the documentary and she came away with an appreciation of him, and I think that’s the aspect in how the documentary succeeded. It seems a little different to someone who already knows a lot about him. (Though I did enjoy it…how often are there Hamilton documentaries on TV at all? I’ll take what I can get!)

[Reply]

Lin-Manuel Miranda has gone on to prove that you CAN make rap and Hamilton relevant, but only if you do it thoughtfully and do it well!

[Reply]

Leave a Comment