Report of the Commission on Unalienable Rights

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo gave an impressive speech in Philadelphia last week about the Report of the Commission on Unalienable Rights which he commissioned last year. It was refreshing to hear a highly placed member of the government demonstrate an unabashed, clear-eyed understanding of the principles that made the United States what it is. Pompeo is demonstrating leadership and vision by clearly articulating not only where we’ve been, but hope for where we can go. Putting together a comprehensive document of this scope, was necessarily the product of thoughtful discussion, contemplation and consideration. It’s not possible to put something like this together without sharpening one’s understanding and thinking.

The commission was not chartered to provide specific policy recommendations but rather to provide a philosophical framework within which the Department of State should derive policy. It used as its starting point the United States’ founding documents, a historical summary of civil rights in the United states and finally builds on the 1948 UN General Assembly of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The roughly 60 page report is well written and illuminates a number of issues, comes to certain conclusions, but lives up to it’s non-partisan charter. That in itself, is interesting. It shows that it’s possible to examine facts and come to a consensus. That consensus might align with one partisan faction or another, but that should not call its validity into question. Sometimes one side is right.

Clearly, there was contention between the members of the commission, and, just as clearly, one perspective largely prevailed. But the fact that they all signed the completed work, seems to indicate that consensus was reached, even if it had to be couched in very careful terms.

For instance, while Secretary of State Pompeo appears satisfied with the outcome, and in his remarks distinctly ties the founding principles back to a perception of human-worth as God-given, the commission’s report dances around how to discriminate between a fundamental human right – such as life, and “positive” human right which is subject to economic or cultural feasibility – such as the “right” to privacy.

The reason for the dance is that acknowledging an inherent and inalienable attribute requires one to define why it should be so. The founders didn’t have a problem with this, they called it out explicitly and built their arguments on man being the explicit creation of God, and “created” with value. Pompeo points out in his speech that the founders didn’t spend a lot of time focused on these suppositions because they felt it was pretty self-evident.

The report manages to come around to a reasonable, if not exactly precise distinction between a basic human right – genocide = bad, and a positive human right – privacy. As defined by the report, positive human rights are those that exist with the forbearance or at the behest of the state. While more fundamental rights, like the right to not be tortured, are more self-evident according to all the signatories of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

It is no departure from that affirmation to recognize that certain distinctions among rights are inherent in the Universal Declaration itself, as well as in the positive law of human rights developed in light of the UDHR. International law accepts that some human rights are absolute or nearly so, admitting of few or no exceptions, even in times of national emergency, while others are subject to many reasonable limitations or are contingent on available resources and on regulatory arrangements. Some norms, like the prohibition on genocide, are so universal that they are recognized as norms of jus cogens — that is, principles of international law that no state can legitimately set aside — while other norms are open to sovereigns to accept or not. The application of certain human rights demands a high degree of uniformity of practice among nations, as in the prohibition of torture, but others allow of considerable variation in state practices, as in the protection of privacy. The work of the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor reflects such considerations.

Internal philosophic consensus doesn’t quite carry the same authority as is implicit in saying – God created people and has assigned equal worth to each, therefore, they deserve the same opportunities. The authors of the report go through the same contortions that those of the UDHR did,

The document intentionally refrains from specifying the ultimate source

of that dignity, but it does make clear that human dignity is inherent: it pertains to human beings solely because they are human beings. It cannot be granted by any authority. It is not created by political life or positive law but is prior to positive law and provides a moral standard for evaluating positive law. And no human life can be stripped of its dignity. Finally, the Universal Declaration’s integrated set of rights begins to flesh out the meaning and implications of human dignity by emphasizing the flourishing in community that liberty makes possible. In all these ways, the idea of human dignity at the heart of the Universal Declaration converges with the idea of “unalienable rights†in the American political tradition. It is no stretch to suggest that “unalienable rights†were the form in which the American founders gave expression to the idea of an inherent human dignity.

The authors of the report contend that “new” rights may need to be acknowledged or promoted through positive law. This is one of the stranger sections of the report. On the one hand they say that you can’t pick and choose between the rights of the UDHR, and on the other, they acknowledge that, to paraphrase Orwell, some rights are more equal than others.

It must be recognized that along with civil and political rights, social, economic, and cultural rights, too, are an integral part of the Universal Declaration’s fabric. At the same time, it needs to be appreciated that the UDHR presents and promotes the two groups of rights in different ways.

The reality is, the definition of what constitutes a “human right” was bastardized by the UDHR and this report is in part an effort to disentangle moral imperatives (don’t torture people) from Government dependent pseudo “rights.”

However, a direct appeal to human dignity by itself is inadequate to the task of distinguishing between legitimate and unfounded claims of right. Dignity itself is a deeply contested idea, the content of which varies dramatically not only across cultures but even within our modern pluralistic societies. On some of the most deeply divisive contemporary moral issues

— for instance, the legalization of voluntary euthanasia

— dignity-based arguments feature prominently on both sides of the debate.

and recognizing the inadequacy of the state as arbiters of morality

In addition, it is crucial to appreciate that the established law of human rights cannot answer the important questions that by definition spill over the boundaries of existing positive law. The very notion of a human right is that of a right inherent in human beings and not dependent for its existence on the enactment of any state or international institution. Positive law can establish and clarify a state’s enforceable obligation to individuals and to other states. But positive law — whether that of a nation-state or of the international legal order — does not

create a human right, nor can its silence or conduct nullify a human right. The fact that positive law has recognized something as a human right, moreover, does not place that law beyond reproach, reconsideration, and revision. While human rights are the standard against which we judge the justice of positive laws, no nation-state or international institution has a monopoly or final word on what human rights require. In short, inasmuch as human rights provide core principles by which to judge the justice or injustice of positive laws, no positive law — whether national or international — can be considered the ultimate arbiter of human rights.

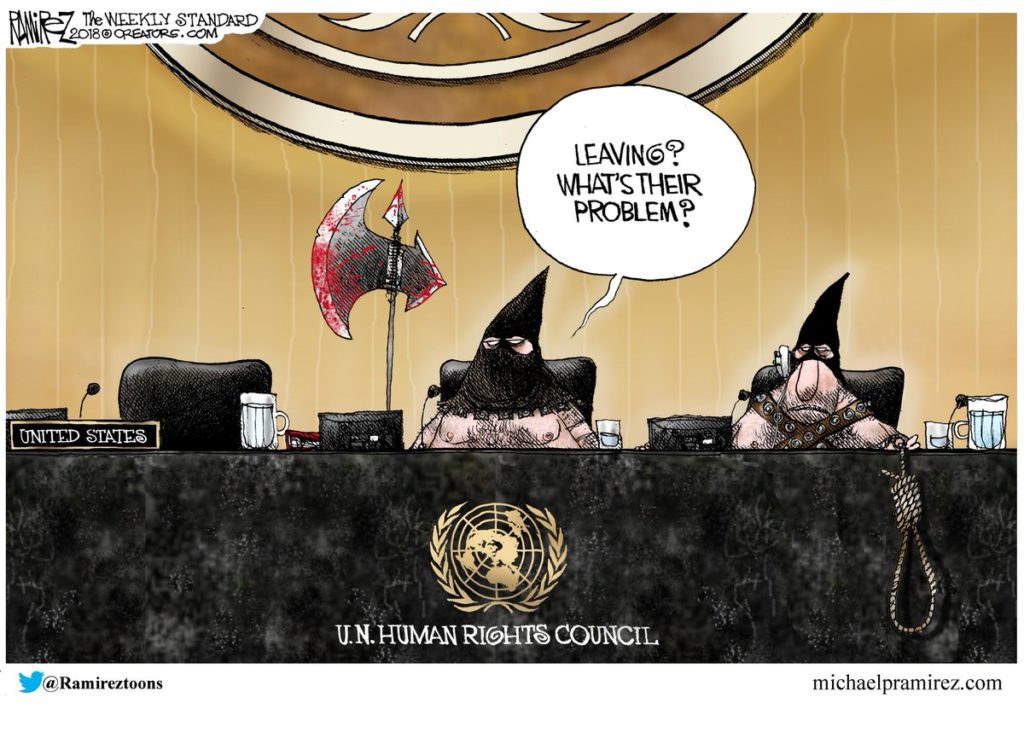

The report’s authors are not fools and recognize how “human rights” is used as a political tool to achieve political goals by unelected special interest groups that often don’t even represent their own polis.

… the widespread proliferation of non-legal standards — drawn up by commissions and committees, bodies of independent experts, NGOs, special rapporteurs, etc., with scant democratic oversight — gives rise to serious concerns. These sorts of claims frequently privilege the participation of self-appointed elites, lack widespread democratic support, and fail to benefit from the give-and take of negotiated provisions among the nation-states that would be subject to them.

The report is worth reading.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

1 comment

[…] Add this report to the stack – those of you who are more philosophic of mind may find it worth… […]

Leave a Comment