Revolutionary Founders

Revolutionary Founders is a collection of essays written by a group of different historians, 22 in fact. From the outset, it is clear that this is not going to be your run-of-the-mill popular biography/history. This is more an academic and esoteric work. The editors set the readers expectations in the introduction. They don’t hide their opinions.  Here are a few of them:

Revolutionary Founders is a collection of essays written by a group of different historians, 22 in fact. From the outset, it is clear that this is not going to be your run-of-the-mill popular biography/history. This is more an academic and esoteric work. The editors set the readers expectations in the introduction. They don’t hide their opinions.  Here are a few of them:

Political, social, and economic equality were not what the framers had in mind.

In accounts of the era that focus on its best-known leaders, the failure to include radical impulses from below results in a deficient, truncated history.

The foreshortened view of radicalism in America prevents us from grasping powerful crosscurrents of the founding era.

It was interesting to see where the essay writers would take this. In his book, Radicalism of the American Revolution, Gordon S. Wood suggests that the American Revolution was a much more radical revolution than currently thought. However, the focus of Wood’s book is on society as a whole. In this collection of essays, most of the authors write about lesser known individuals from the lower classes – and most of them are fairly objective in how they support their respective theses.

While many, if not most of the subjects covered in the book were lesser known, some will appear as familiar characters to students of the American Revolution. However, no one from the aristocracy appears as a primary character in any of the essays. One of the authors, Jill Lepore, sums up her feelings on why that is when she refers to the version of history that serves as our national heritage as “comic book.” The subject of her essay is Thomas Paine, who was definitely not of the genteel class. She laments the lack of credit he receives.

Thomas Paine, is at best, a lesser founder. In the comic-book version of history that serves as our national heritage, where the Founding Fathers are like the Hanna-Barbera SuperFriends, Paine is Aquaman to Washington’s Superman and Jefferson’s Batman; we never find out how he got his superpowers, and he only shows up when they need someone who can swim.

As cute as this analogy is, Lepore goes overboard in her attempt to correct the misapprehension of American history that so frustrates her. Her disdain for the popular reverence of the Founders is palpable. It might be simplistic, but that doesn’t mean it’s not merited. For example, Washington is called the indispensable man for a reason. He was. However, that does not mean that there weren’t others who could also lay claim to that title – at various points. One could make a compelling argument that Hamilton was indispensable for his role of writing the Federalist, that Franklin was indispensable for getting the French on board, and that Paine was indispensable for his contributions of Common Sense and The Crisis Papers. Without the contributions of these Founders things might have ended up very differently. The point is that they were parts of a whole. However, Washington was not only indispensable, he was uniquely so. Arguing about the relative merits of Paine in comparison to Washington is as juvenile as Lepore’s comic book analogy.  Paine played an important role, and one for which America owed him a debt of gratitude. However, as Lepore points out, Paine’s post-war political views diverged radically from those of Washington, Adams and other luminaries of the American Revolution. He was much more radical and supportive of the French Revolution. What Lepore fails to recognize, is that Paine’s differences are his support for those things that in large part made the French Revolution a bloody failure, and what made the course of  the American Revolution so different from that taken by the French.  She correctly identifies Paine’s socialistic tendencies but ignores the ramifications. It never seems to occurs to her that Paine could have been wrong!

As cute as this analogy is, Lepore goes overboard in her attempt to correct the misapprehension of American history that so frustrates her. Her disdain for the popular reverence of the Founders is palpable. It might be simplistic, but that doesn’t mean it’s not merited. For example, Washington is called the indispensable man for a reason. He was. However, that does not mean that there weren’t others who could also lay claim to that title – at various points. One could make a compelling argument that Hamilton was indispensable for his role of writing the Federalist, that Franklin was indispensable for getting the French on board, and that Paine was indispensable for his contributions of Common Sense and The Crisis Papers. Without the contributions of these Founders things might have ended up very differently. The point is that they were parts of a whole. However, Washington was not only indispensable, he was uniquely so. Arguing about the relative merits of Paine in comparison to Washington is as juvenile as Lepore’s comic book analogy.  Paine played an important role, and one for which America owed him a debt of gratitude. However, as Lepore points out, Paine’s post-war political views diverged radically from those of Washington, Adams and other luminaries of the American Revolution. He was much more radical and supportive of the French Revolution. What Lepore fails to recognize, is that Paine’s differences are his support for those things that in large part made the French Revolution a bloody failure, and what made the course of  the American Revolution so different from that taken by the French.  She correctly identifies Paine’s socialistic tendencies but ignores the ramifications. It never seems to occurs to her that Paine could have been wrong!

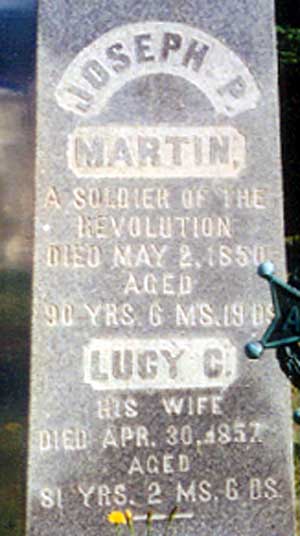

Fortunately, many of the other essayists in the book do a better job of presenting their views objectively. One of the very best was Philip Mead’s on Private Joseph Plumb Martin.   Private Martin had his memoir published anonymously in 1830. It didn’t go over well with the public at the time because it painted a picture that wasn’t necessarily flattering to some of the leaders of the Revolution. Mead goes through the memoir and points out how startlingly accurate it was, by verifying some of the events in the book. Private Martin was a seven-year veteran of the Continental Army and fought in nearly every major battle between 1776 and 1782. He was justifiably angered by the lack of recognition that the common man received for his role in the Revolution:

I was at the siege and capture of Lord Cornwallis, and the hardships of that were no more to be compared with this [the Siege of Fort Mifflin], than the sting of a bee is to bite of a rattlesnake.  But there has been but little notice taken of it, the reason of which is, there was no Washington, [Israel] Putnam, or [Anthony] Wayne, there. Had there been, the affair would have been extolled to the skies. No, it was only a few officers and soldiers who accomplished it in a remote quarter of the army. Such circumstances and such troops generally get but little notice taken of them, do what they will. Great men get great praise; little men, nothing. But it always was so and always will be.

Martin’s motivation for writing his memoir arose partially from the controversy over the 1818 Pension Act and out of a desire to set the historical record straight. He chafed at those who sought to “vilify” the service of the rank and file as less than patriotic, or who minimized the sacrifices they made for the cause. His anger shows through:

Martin’s motivation for writing his memoir arose partially from the controversy over the 1818 Pension Act and out of a desire to set the historical record straight. He chafed at those who sought to “vilify” the service of the rank and file as less than patriotic, or who minimized the sacrifices they made for the cause. His anger shows through:

Almost everyone one has heard of the soldiers of the revolution being tracked by the blood of their feet on the frozen ground, this is literally true, and the thousandth part of their suffering has not, nor will every be told.

After the battle at Fort Mifflin, Martin sarcastically reminisces,

While we lay here there was a Continental Thanksgiving ordered by Congress … We had nothing to eat for two or three days previous … but we must now have what Congress said, a sumptuous Thanksgiving to close the year of high living we had now nearly seen brought to a close. Well, to add something extraordinary to our present stock of provisions, our country, ever mindful of its suffering army, opened her sympathizing heart so wide, upon this occasion, as to give us something to make the world stare. And what do you think it was, reader? Guess. You cannot guess, be you as much of a Yankee as you will,. I will tell you; it gave each and every man a half a gill of rice and a tablespoonful of vinegar!

After the war Martin and many others lamented their treatment by the nation for whose formation they had sacrificed so much.

When the country had drained the last drop of service it could screw out of the poor soldiers, they were turned adrift like old-worn-out horses, and nothing said about land to pasture them on. Congress did, indeed, appropriate lands under the denomination of “Soldier’s lands,” in Ohio state, or some state, or future state, but no care was taken that the soldiers should get them. No agents were appointed to see that the poor fellows ever got possession of their lands; no one ever took the least care about it, except a pack of speculators, who were driving about the country like so many evil spirits, endeavoring to pluck the last feather from the soldiers.

Mead does a great job laying out Martin’s case for the patriotism of the common man during the Revolution (some were disparaging their role), and for the sad treatment of an ungrateful public, after the fact. Private Joseph Plumb Martin’s memoir is one that’s been added to the “to-read” list at WWTFT.

The next essay in the book continues Mead’s underlying theme of the common man paying for the brunt of any war. Michael A. McDonnell focuses on “The Spirit of Leveling” in revolutionary Virginia. McDonnell shows how the different patriot factions during the Revolution needed one another and how the lower classes were able to exert leverage on the aristocracy. McDonnell quotes Edward Wright, one of his essay’s exemplars, “the Rich wanted the Poor to fight for them, to defend there [sic] property, whilst they refused to fight for themselves.” Men like Wright were not content to go along with blatantly unfair mobilization laws that disproportionately burdened small farmers. They refused to be imposed upon by unjust laws. McDonnell points out,

These claims for equality in the midst of Revolutionary War had important results. For one thing, ordinary white Virginians, through their collective actions, were able to manipulate the recruitment laws, even to the point of crippling mobilization in Virginia. When unjust draft laws were introduced, Virginians protested sufficiently to get them dropped or changed.

McDonnell identifies an aspect of the Revolution in Virginia that is not commonly pointed out. Recent books reviewed at WWTFT, such as a Leepson’s book on Lafayette and Unger’s biography of Patrick Henry, both refer to the difficulty in mobilizing troops in Virginia. Neither go into much detail as to why. McDonnell’s essay does that, and shows how this feisty group continued to make their concerns visible even after the war. George Mason, author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, was forced to concede, “The people in this Part of Virginia are well disposed to do everything in their Power to support the war, but the same Principles which attach them to the American Cause, will incline them to resist Injustice or Oppression.” Because patriot leaders were forced to rely on an army of ordinary men, this fostered the belief that all ranks of men had the right to forcefully express their ideas about governance.

Jon Butler provides an interesting overview of how religious freedom took root in Virginia. Butler’s essay provides a nice complement to Unger’s book on Patrick Henry, in which Henry “makes his bones” (so to speak), by going against the State-supported Anglican church. Butler develops the role of Virginia Baptists in the American Revolution.   The Baptists figured out ways to align their cause for religious freedom with the cause of American independence, thus allying themselves with the local government which had theretofore been their antagonist.

Between 1770 and 1776, Virginia Baptists found ways to intensify their protests and demands while aligning themselves with political protests about British incursions against colonial rights and privileges.

If Henry started the ball rolling with his defense of Baptists and his landmark court case against the Anglicans, he didn’t go as far as Madison in his advocacy for religious practice as independent of State interference. In 1784 Patrick Henry drafted a “general amendment” bill to support protestant teachers through tax levies. He sought to recognize the post-Revolutionary abolition of “all distinctions of pre-eminence amongst the different societies or communities of Christians.”

If Henry started the ball rolling with his defense of Baptists and his landmark court case against the Anglicans, he didn’t go as far as Madison in his advocacy for religious practice as independent of State interference. In 1784 Patrick Henry drafted a “general amendment” bill to support protestant teachers through tax levies. He sought to recognize the post-Revolutionary abolition of “all distinctions of pre-eminence amongst the different societies or communities of Christians.”

Madison attacked it ferociously in an anonymous essay he sent to the Virginia Legislature. He gave two reasons for his attack on Henry’s bill:

First, Madison articulated a broadly rationalist and secular argument for separating religion from government. Second, he simultaneously employed religious reasons for opposing Henry’s scheme. He argued that taxing citizens was “adverse to the diffusion of the light of Christianity,” that Christianity “disavows a dependence on the powers of this world,” and that Hnery’s bill established the “Civil Magistrate [as] a competent Judge of Religious Truth,” a fact every Virginia Baptist knew from bitter experience to be false.

The Virginia legislature tabled Henry’s general assessment bill.

Madison earned the respect and trust of the Baptists and was able to prevent their outright opposition to the Constitution a few years later, partly on the basis of his promise to fight for a Bill of Rights, and partly on the basis of this history.

Butler points out that,

… Virginia Baptists helped shape a uniquely American future where organized religion was free to practice on its own and where government was obligated to honor the spiritual independence of groups and individuals alike.

Many of the essays in this book bring out little known characters and facts which shed light on some of the less superficial aspects of the American Revolution. Unfortunately, in a book of this sort, it is difficult to write a review that does justice to all contributors. It is not a book that covers a single topic, instead it is a collection of many topics, unified under the themes listed at the onset of the review. It is simply impractical to cover every essay.

Revolutionary Founders will become a resource at WWTFT, both for the essays within it and for the sources referenced. (Although this reviewer is not in agreement with all of the contentions in the book.)  Quite a few of the essays, are  summaries of books written by their authors.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment