Rise and Fight Again by Spencer C. Tucker

Rise and Fight Again

Rise and Fight Again

The Life of Nathaniel Greene

By Spencer C. Tucker

This short biography of Nathaniel Greene is packed with insight and erudition. It is the third in an excellent series published by ISI that this reviewer has read. Â (See The Cost of Liberty, reviewed here) The book has been on this reviewer’s ever expanding list for some months, and got pushed up in the queue after reading John Oller’s excellent biography of Francis Marion (reviewed here).

It is interesting to read these two books in conjunction with one another as they are complementary in their coverage of Greene. In Oller’s book we see a general struggling to balance the egos of southern militia leaders as seen from Marion’s point of view. In Tucker’s biography we see a more sympathetic view of Greene’s management in a leader who has “been there” and struggled with his own ambitions.

In 1777, Silas Deane, one of the American ambassadors to France authorized by congress to recruit military specialists, enlisted French army general Philip Charles Tronson Du Coudray to replace Greene’s friend Knox, as head of the Continental Army’s artillery.

Knox and Greene were close friends and Knox had already proven his worth as far back as the winter of 1775-1776, when he accomplished the herculean task of bringing 60 tons of artillery captured at Fort Ticonderoga to Continental Army camps outside Boston. Greene, like many other men in the Continental Army’s officer corp was incensed “when foreigners of dubious distinction were given positions of leadership over deserving American officers.”  This not to say that there weren’t also some very good appointments, but Tucker seems to suggest that Coudray was a bit of a fop. The seeming injustice was more than Greene could bear.

Greene wrote to John Adams, one of his allies in Congress, and complained that important positions like this should not be entrusted to foreigners, especially at the cost of someone as valuable as Knox. Â Adams agreed with him and tried to mollify Greene by assuring him that Deane had overstepped and that Coudray would not have much support in Congress.

All might have been well, had not Greene then discovered that Coudray’s commission in the Continental Army preceded his own by 8 days, making him senior to Greene. Â This was too much for the young Greene’s ego.

Ignoring Adams’s sympathetic response, and apparently without first consulting Washington, Greene now took the most ill-considered action of his military career.

He bypassed his chain of command, went over Adams’s head, and wrote directly to the president of Continental Congress, John Hancock threatening to resign.  Two other officers, Sullivan and Knox, issued similar threats.

This did not go over well with Congress and was probably the last thing that Washington needed to deal with.

… On July 7, 1777, Congress passed a resolution instructing Washington to convey its displeasure to the three Generals [Greene, Knox, Sullivan] and inform them that it considered their letters “an attempt to influence their Decisions, and invasion of the liberties of the people, and indicating a want of confidence in the justice of Congress.” The resolution went on to demand that the three generals “make proper acknowledgements of an interference of so dangerous a  tendency,” and it concluded with an invitation to the three to make good on their threat: “But if any of those officers are unwilling to serve their country, under the authority of Congress, they shall be at liberty to resign their commissions and retire.” At the same time, however, Congress also chided Deane for entering into agreements that superseded American officers.

That same day, July 7, Adams wrote Greene a long letter noting the resolution and chastising him for his conduct. Misspelling his name, Adams reminded my Friend General Green of his own misgivings and those of members of Congress about the Du Coudray appointment and telling him that he should have a private letter instead of a public one threatening resignation. Greene, Sullivan, and Knox, he said, had been guilty of “Rashness, Passion, and even Wantonness in this Proceeding.” Adams urged Greene to apologize and declare publicly that the had “the fullest Confidence in the Justice of Congress and their Deliberations for the public Good.” If he could not do this in “truth and Sincerity,” then Greene “ought to leave the service.” Green apparently never replied. His friendship with Adams now ended. Â Although Adams wrote to Greene in March 1780 from Paris, it was months before the letter arrived, Greene did not respond until January 1782, and there is no evidence that Adams ever received it.

Greene neither apologized nor resigned, but he also never again attempted to influence Congress in such a manner. On August 11, 1777, Congress decided to make Du Coudray “Inspector General of ordinance and military manufactories.” But just two months later the Frenchman drowned while attempting to ride his horse on the Schuylkill Ferry.Â

One has to wonder if this affair was present in Greene’s mind when years later he found himself of the other side of a similar situation of his own creation.  In 1781 Greene, then in charge of the Continental army in the south, commissioned Peter Horry and Hezekiah Maham as lieutenant colonels to raise two elite corps of dragoons that would be more reliable than mounted militia.  It seemed like a good idea at the time.  Unfortunately the two men did not get along and were fiercely jealous of one another. To make matters worth, Greene dated both of their commissions on the same day.  This further exacerbated tensions between the two men as both thought they should be senior to the other.  Thus Greene created a headache for himself, Francis Marion and South Carolina Governor Rutledge.

It’s hard to say if Greene learned from this experience. However, his experience under the leadership of George Washington is evident in his management style in other ways. Washington’s brilliance as a leader shines through this biography of Greene as it does in most books in which Washington makes an appearance. Washington had a knack for picking good people and sticking with them even when they made mistakes. Greene made a terrible mistake early in his career when he urged Washington to try and retain Fort Washington in New York. Against his own inclination to abandon the fort, Washington allowed Greene to make the call and use his own judgement.

It’s hard to say if Greene learned from this experience. However, his experience under the leadership of George Washington is evident in his management style in other ways. Washington’s brilliance as a leader shines through this biography of Greene as it does in most books in which Washington makes an appearance. Washington had a knack for picking good people and sticking with them even when they made mistakes. Greene made a terrible mistake early in his career when he urged Washington to try and retain Fort Washington in New York. Against his own inclination to abandon the fort, Washington allowed Greene to make the call and use his own judgement.

The resulting loss of men taken prisoner and supplies was staggering and ranks with the loss of Charleston in 1780 as “one of the two worst Patriot defeats of the entire war.”

Washington accepted responsibility, but only shielded Greene from the consequences, rather than his culpability when explaining the situation to Congress.

Despite what Washington had written to Congress, he neither fired Greene or chose to make him a scapegoat. Perhaps Washington remembered his own difficult learning process in the French and Indian War, and no doubt he knew in his heart that the responsibility for the loss was shared. He recognized Greene’s undoubted leadership abilities and organizational skills. Military knowledge would come with time and experience. A chastened and grateful Greene repaid his commander’s confidence with unswerving loyalty. Throughout the war, he remained the commander in chief’s stalwart defender and champion.

Tucker’s biography depicts a loyal follower of Washington who became a brilliant strategist in his own right.  Both he and Washington adopted similar tactics to those employed by Schuyler in 1777 (withdrawing before superior strength and forcing the British to over extend already long supply lines).  Tucker gives a blow by blow,  account of Cornwallis’s army chasing Greene all over the south. However, this is not to say that Greene did not offer battle when advantageous to do so as at Guilford Courthouse.  Greene offered the following realistic assessment to Washington,

The Honour of the Day terminated in favour of the Enemy, but their losses being infinitely greater than ours, I trust will ultimately prove advantageous to us.

Cornwallis attempted to describe it as a glorious victory, but when the details were reported to parliament as such, opposition leader Charles Fox channeled the ancient king Pyrrus of Epirus and replied sardonically, “Another such victory would ruin the British Army.”

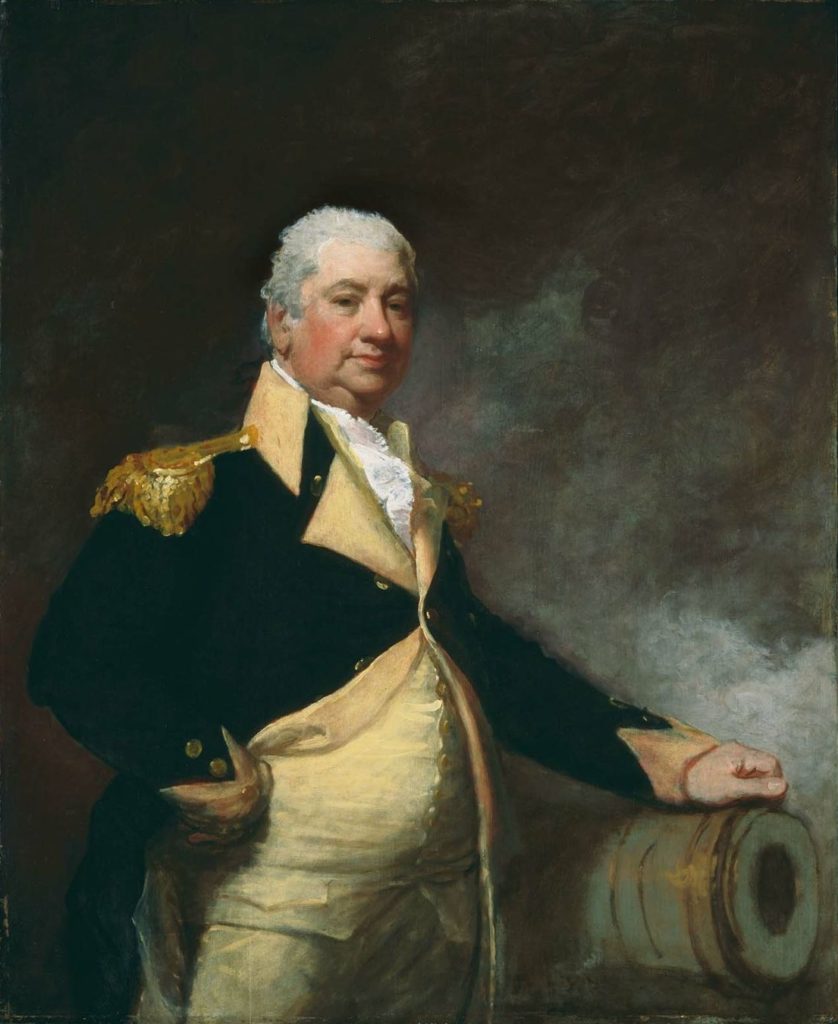

By carefully husbanding his meager resources, Greene was able to liberate the South, and was one of America’s greatest generals. He was a brilliant strategist and his campaigns in the south are still studied today. Like Washington, he did not live long after retiring from public service. Â He died in 1786 in an uncertain financial situation. Â In order to clothe his men, he had offered a personal guarantee to the merchants of Charleston, and the creditors were after their money. His only wealth was bound to the property and money given to him by a grateful South Carolina and Georgia. Â Only after his death did Congress pass, and Washington sign, an act to indemnify the Greene estate to clear the debts incurred by Greene for maintenance of the Southern Army.

By carefully husbanding his meager resources, Greene was able to liberate the South, and was one of America’s greatest generals. He was a brilliant strategist and his campaigns in the south are still studied today. Like Washington, he did not live long after retiring from public service. Â He died in 1786 in an uncertain financial situation. Â In order to clothe his men, he had offered a personal guarantee to the merchants of Charleston, and the creditors were after their money. His only wealth was bound to the property and money given to him by a grateful South Carolina and Georgia. Â Only after his death did Congress pass, and Washington sign, an act to indemnify the Greene estate to clear the debts incurred by Greene for maintenance of the Southern Army.

Harry “Light Horse” sums up the impression with which Tucker leaves his reader:

… pure and tranquil from the consciousness of just intentions, the undisturbed energy of his mind was wholly devoted to the effectual accomplishment of the high trust reposed in him.Â

A Word About the Binding and Presentation

ISI Books has done a fantastic job with the presentation of this book (and others in the series.) Rise and Fight Again is a pleasure to hold and read. This reviewer even eschewed his normal markup of the review copy. This is a quality production and it will hold a place in the WWTFT library for a long time to come. The text is nicely presented in Adobe Garamond 11pt font throughout a concise, but thorough 215 pages. Additionally, there are about 20 pages of footnotes.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment