The Admiral And The Ambassador

The Admiral and The Ambassador follows the pattern set out by many novelists who incorporate multiple time periods into their stories. The story hops back and forth, slowly converging on the “current” timeline. What is interesting about this book is that it isn’t fiction. Author Scott Martelle succeeds in telling two stories at once. There is Jones’ own story, and then the story of the man who made it his mission to find the long lost hero’s remains. Because of the time periods covered, this reviewer found The Admiral and the Ambassador to be a great addendum to some of the other books he has recently read — John Barry an American Hero In The Age of Sail, The Shining Sea, and Bruce Catton’s Civil War Trilogy: ” The Coming Fury, Terrible Swift Sword, and Never Call Retreat.

The Admiral and The Ambassador follows the pattern set out by many novelists who incorporate multiple time periods into their stories. The story hops back and forth, slowly converging on the “current” timeline. What is interesting about this book is that it isn’t fiction. Author Scott Martelle succeeds in telling two stories at once. There is Jones’ own story, and then the story of the man who made it his mission to find the long lost hero’s remains. Because of the time periods covered, this reviewer found The Admiral and the Ambassador to be a great addendum to some of the other books he has recently read — John Barry an American Hero In The Age of Sail, The Shining Sea, and Bruce Catton’s Civil War Trilogy: ” The Coming Fury, Terrible Swift Sword, and Never Call Retreat.

If those titles seem disparate, they reflect the span of time covered in Martelle’s excellently researched book. Martelle starts his tale with a brief recounting of the death of John Paul Jones in Paris, July 18, 1792. Jones was suffering from chronic pneumonia and failing kidneys when he died alone in his Paris apartment. The French Revolution was in full swing and were it not for the beneficence of one of Jones’ few friends, a Royal bureaucrat by the name of Francois Pierre Simonneau, Jones would have ended up in a pauper’s grave, his remains lost amongst those of the thousands who perished during the French Revolution. Simonneau paid for Jones’ funeral arrangements himself.

Jones’ body was carefully prepared and placed into a lead coffin. He was dressed in linen, and carefully packed with hay to keep his body from being jostled, in anticipation of its being shipped back to America at some point. Simonneau was thinking ahead.

Jones’ body was carefully prepared and placed into a lead coffin. He was dressed in linen, and carefully packed with hay to keep his body from being jostled, in anticipation of its being shipped back to America at some point. Simonneau was thinking ahead.

The corpse carefully prepared, the coffin was then sealed by soldering the lid in place. Finally, a small hole was drilled in the top. This was not an emergency air hole, but the port used to fill the coffin with alcohol as a means of preserving the body. Once filled with alcohol, the hole was soldered shut and Jones was interred in a protestant cemetery, about the only place in Catholic France that he could be buried.

As the turmoil in France increased Jones’ whereabouts were forgotten and even the cemetery in which he was buried was covered over, and the land sold for other uses, including as a dump, and as a dog cemetery. A variety of businesses in ramshackle buildings later constructed over the site further obscured what lay almost 20 feet below the surface.

But Martelle lays out the story much more elegantly than that. For the first half of the book, the author jumps between Jones’ career and that of Ambassador Horace Porter. For Jones, it was the story of his time in the US and Russian Navies*, culminating with his death in Paris. Porter’s story begins during the Civil War. Unlike Jones, while a military man, Porter was not a sailor.

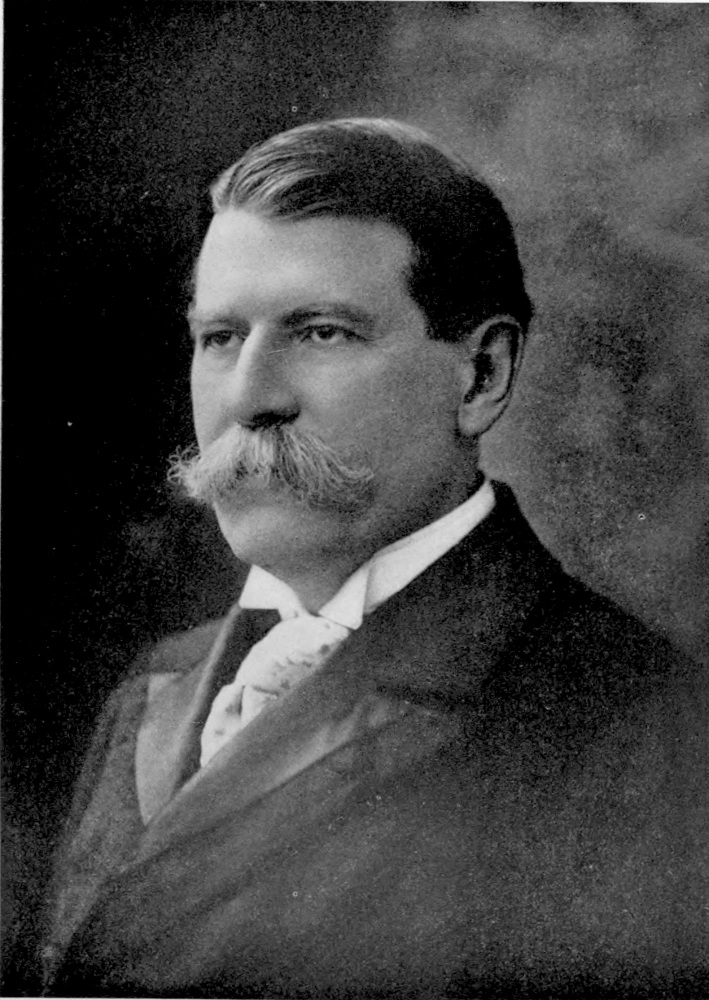

Porter was a Union Civil War General who was a protege of U.S. Grant. Grant saw something in Porter and brought him along in his career. General Porter followed Grant into politics but steered clear of the corruption that characterized Grant’s administration. However, he remained loyal to his patron, and when Grant died, Porter played a major role in ensuring that Grant’s tomb was completed. Porter made his fortune working for the Pullman train car company, but became a significant player in Republican politics and worked hard to get his friend William McKinley elected.

Porter was a Union Civil War General who was a protege of U.S. Grant. Grant saw something in Porter and brought him along in his career. General Porter followed Grant into politics but steered clear of the corruption that characterized Grant’s administration. However, he remained loyal to his patron, and when Grant died, Porter played a major role in ensuring that Grant’s tomb was completed. Porter made his fortune working for the Pullman train car company, but became a significant player in Republican politics and worked hard to get his friend William McKinley elected.

Upon his election, McKinley chose Porter as the nation’s second ambassador to France. The United States did not have ambassadors prior to 1893. (Prior to that, the highest rank was that of minister, which put American diplomats at a distinct disadvantage when dealing with the emissaries of other countries who were full-fledged ambassadors, one rung up in rank and prestige.)

It was while Porter was serving in France, that the idea of locating and retrieving Jones’ remains began circulating back in the United States. According to Martelle, the circumstances that brought this idea to the fore, had everything to do with the politics surrounding the Spanish-American war, precipitated over Spain’s attempts to control its wayward Cuban colony. With the destruction of the battleship Maine in Havana harbor, the war became a certainty, despite McKinley’s reticence to involve the country in a dispute with a European power. The United States’ involvement didn’t stop with Cuba, but also extended to the Philippines, where the overwhelming success of Admiral Dewey stoked national enthusiasm for the Navy and resurrected interest in honoring one of America’s first naval heroes, the long lost John Paul Jones.

Porter began to get official and semi-official queries about the possibility of locating Jones’ body. Initially, he delegated the task of researching the burial site to the embassy’s second secretary, Arthur Bailly-Blanchard, who was from New Orleans and fluent in French. However, Bailly-Blanchard didn’t know the ins and outs of navigating the French bureaucracy. For that they enlisted the aid of the editor of a weekly newspaper called Lâ’Echo du Public, Alfred de Ricaudy. Ricaudy had recently been successful in finding the grave of an eighteenth-century French economist who’d died in 1781. Like Jones, his whereabouts had been forgotten in the course of the ensuing years.

Porter began to get official and semi-official queries about the possibility of locating Jones’ body. Initially, he delegated the task of researching the burial site to the embassy’s second secretary, Arthur Bailly-Blanchard, who was from New Orleans and fluent in French. However, Bailly-Blanchard didn’t know the ins and outs of navigating the French bureaucracy. For that they enlisted the aid of the editor of a weekly newspaper called Lâ’Echo du Public, Alfred de Ricaudy. Ricaudy had recently been successful in finding the grave of an eighteenth-century French economist who’d died in 1781. Like Jones, his whereabouts had been forgotten in the course of the ensuing years.

Unfortunately, Ricaudy saw this as a way to milk the U.S. and possibly French Governments out of a fortune. He withheld some critical bits of information and quietly secured a two year option for access to the property encompassing the old graveyard. When Porter and Bailly-Blanchard approached the property owner, this fact came out.

Porter was incensed, but decided to seemingly let the matter drop. His patron McKinley was re-elected, and this meant that Porter wasn’t going anywhere. He could wait.

The next few years were not the happiest of times for Porter. President McKinley, by Martelle’s account, a kind and decent man, was assassinated by a crazed anarchist. His successor, Teddy Roosevelt, didn’t want to make any major changes and kept Porter in his position. However, in 1903 Porter was to lose Sophie, his wife of 40 years. This put him into a profound depression from which he didn’t emerge until Roosevelt reached out to him to resume his search for Jones’ body.

Sophie’s death took the joy from Porter’s life, and his grief turned to depression. He lost interest in the job of ambassador and began talking about resigning and returning to the United States. “He rarely tended to business at all that summer but finally resumed a full schedule of work in late September. Even then, he was something of a recluse, no longer hosting dinners and turning down nearly all social invitations, even those from old friends.

In early October 1903, Porter received a letter from Roosevelt. It could be that Roosevelt, aware of Porter’s floundering emotions, sought to lift the ambassador’s spirits by giving him something other than the mundane duties of the embassy upon which to focus. Or it could be that Roosevelt, knowing that Porter was looking to quit Paris, wanted to ensure that one lingering project would get completed before there was a change.

This was to be Porter’s final mission as ambassador.

Porter became engrossed with his task and proceeded to make arrangements with the property owner and upon securing an agreement (after much wrangling and persuasion), he hired an expert mining engineer to sink vertical shafts through the fill which had been dumped over the site down to the original ground level and below. Porter ended up footing the bill for all of this work – $35,000 – because Congress was unwilling to allocate funds for this, and he chose to go ahead anyway. Later, he would refuse efforts to repay him for his expense.

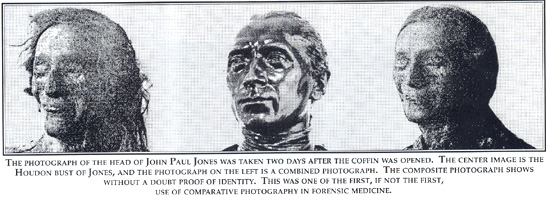

When Jones’ lead casket was finally found, because of the alcohol in which it had been immersed for so long, the body had been remarkably preserved. Porter had succeeded.

Martelle’s story doesn’t end there. He goes on to recount the bureaucratic infighting surrounding the selection of a final resting place for Jones. Roosevelt, a staunch advocate of the Navy, made the final decision. Jones would be interred at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, which was undergoing a complete renovation. Jones would lie under honor guard at the Academy for years before funds were finally raised to provide him a crypt in the basement of the Academy chapel.

Martelle’s account of the efforts to find Jones’ body and of the man chiefly responsible for it, is fascinating and thorough. He manages to incorporate many interesting anecdotes and historical details along the way, all of which add color and texture to the tale, and it’s a tale worth reading.

*Jones, seeking employment after the American Revolution, went to work for Catherine II in Russia. He fought with some distinction in the Black Sea, battling the Turks. However, things didn’t work out quite as he had hoped. Political infighting deprived conspired to deprive him of the recognition he deserved for his successes.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment