The Difference Between Common Law and Civil Law (And Why This Is Important)

Note: The inspiration for this essay come from an excellent article in the Fall 2014 issue of Modern Age, entitled James Monroe And The Sources of American Exceptionalism.

Civil Law

Civil law, sometimes know as Roman law, is law that is updated by “fashionable ideology.”1 That ideology may be summed up in the presumption that human beings are perfectible – or best controlled – under the guidance of a wise state run by experts.  Equality is more important that individuality.  Under this ideology, everything is to be boiled down into a series of (inevitably ruthless) calculations about what is “best” for the common good. The right of the individual is significantly less important.  The “common good” must be achieved at all costs – whether the people want such change or not.  And of course, the state gets to determine the definition for the “common good.”

Civil law, sometimes know as Roman law, is law that is updated by “fashionable ideology.”1 That ideology may be summed up in the presumption that human beings are perfectible – or best controlled – under the guidance of a wise state run by experts.  Equality is more important that individuality.  Under this ideology, everything is to be boiled down into a series of (inevitably ruthless) calculations about what is “best” for the common good. The right of the individual is significantly less important.  The “common good” must be achieved at all costs – whether the people want such change or not.  And of course, the state gets to determine the definition for the “common good.”

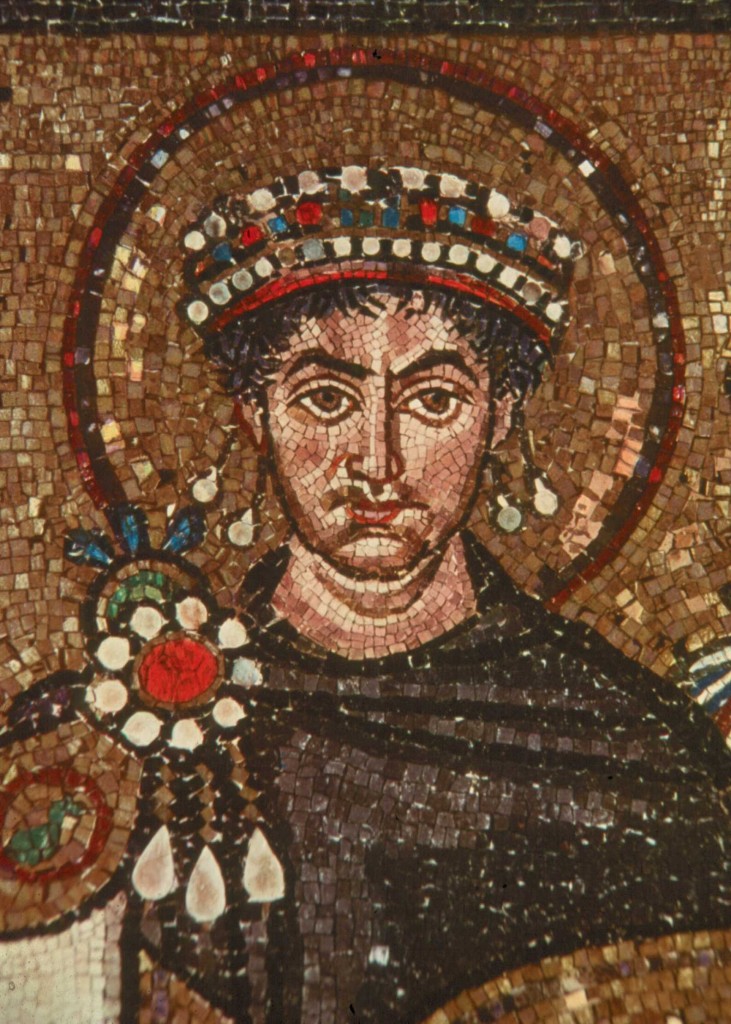

The notion of civil law goes way back to the time of Justinian, the last Roman emperor whose native language was Latin. When he ordered his quaestor, Tribonian, to compile a new codification of Roman law, there was s systematic effort to discard and replace all previous laws.  In a way, this set the precedent for Roman and civil law for succeeding generations.  “… the legal system should be drawn afresh by groups of unelected experts, without input from representatives of the people.”  Justinian’s quaestor, his legal advisor and presumably his team – the work was too big to be done by one person,  compiled the Corpus Juris Civilis.  The Digest was a rewriting of all previous law, while the Codex were the set of all of Justinian’s own edicts.2

According to Wikipidia,

The work as planned had three parts: the Code (Codex) is a compilation, by selection and extraction, of imperial enactments to date; the Digest or Pandects (the Latin title contains both Digesta and Pandectae) is an encyclopedia composed of mostly brief extracts from the writings of Roman jurists; and the Institutes(Institutiones) is a student textbook, mainly introducing the Code although it has important conceptual elements that are less developed in the Code or the Digest. All three parts, even the textbook, were given force of law. They were intended to be, together, the sole source of law; reference to any other source, including the original texts from which the Code and the Digest had been taken, was forbidden. Nonetheless, Justinian found himself having to enact further laws and today these are counted as a fourth part of the Corpus, the Novellae Constitutiones (Novels, literally New Laws). — emphasis WWTFT

The work was directed by Tribonian, an official in Justinian’s court. His team was authorized to edit what they included. How far they made amendments is not recorded and, in the main, cannot be known because most of the originals have not survived. The text was composed and distributed almost entirely in Latin, which was still the official language of the government of the Empire in 529–534, whereas the prevalent language of merchants, farmers, seamen, and other citizens was Greek. By the early 7th century, the official government language had become Greek during the lengthy reign of Heraclius (610–641).  — emphasis WWTFT

How far the Corpus Iuris Civilis or any of its parts was effective, whether in the east or (with reconquest) in the west, is unknown. However, it was not in general use during the Early Middle Ages. After the Early Middle Ages, interest in it revived. It was “received” or imitated as private law and its public-law content was quarried for arguments by both secular and ecclesiastical authorities. This revived Roman law, in turn, became the foundation of law in all civil law jurisdictions. The provisions of the Corpus Juris Civilis also influenced the Canon Law of the church: it was said that ecclesia vivit lege romana — the church lives by Roman law.[2] Influence on the common-law systems has been much smaller, although some basic concepts from the Corpus have survived through Norman law – such as the contrast, especially in the Institutes, between “law and custom (lex et consuetudo)“. The Corpus continues to have a major influence on public international law. Its four parts thus constitute the foundation documents of the Western legal tradition.  Wikpedia — emphasis WWTFT

Civil law saw a renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers became enamored with the idea of perfecting justice by boiling the law down and codifying it universally. Â After all, human beings were suddenly assumed to be “perfectible,” at least in terms of being perfectly rational.

The idea of codification re-emerged during the Age of Enlightenment, when it was believed that all spheres of life could be dealt with in a conclusive system based on human rationality, following from the experience of the early codifications of Roman Law during the Roman Empire. Â Wikipedia

For much of European history, this was the pattern, law was handed down by the emperor du state.  For instance under the so-called Holy Alliance of the early 19th Century, Russia, Prussia and Austria followed this mode.  In Russia, Catherine the Great appointed a legislative commission to produce a code of civil law.  This was known as a наказ (nakaz).  It borrowed heavily from enlightenment thinkers and was an example of a legal code assembled by “experts” or the intellectuals of the day.

It was compiled as a guide for the All-Russian Legislative Commission convened in 1767 for the purpose of replacing the mid-17th-century Muscovite code of laws with a modern law code. Catherine believed that to strengthen law and institutions was above all else to strengthen the monarchy.  Wikipedia emphasis WWTFT

Consequently, Catherine didn’t adopt all of the enlightenment thinkers’ recommendations on governance.

Catherine’s Instruction to the Legislative Commission gave an in-depth description of the state of the nation at the time it was written (1764).[2] Eighteen months in the making, the Nakaz was written with the intention of providing an unambiguous description of the existing laws. Though Catherine based her writing heavily on the Enlightenment of Western Europe, she merely utilized some of the broader ideas of the movement, such as equality under the law, to strengthen autocracy.[3] Montesquieu, whose works heavily influenced Catherine, wrote of such things as a divided government (where the power is split between the executive and legislative bodies) and a monarchy made up of three estates.[4] Catherine tactfully ignored these ideas in favor of an absolutist bureaucratic monarchy.[5]The Nakaz was written as a way to argue for the already existing system rather than bring about any serious change. … Wikipedia emphasis WWTFT

If one arbitrarily can choose how “enlightened” one is and can choose and modify the law at will, then one is at best the source of enlightenment, or in reality, a despot – e.g. someone who rules with all the power in their hands.

Prussia, another member of the Holy Alliance, began under Frederick the Great, to compile the Prussian civil code and promulgated it under his successor, Frederick William II.

The Prussian Civil Code, a product of the 18th-century Enlightenment, contained many elements of constitutional and administrative law. It attempted to be totally comprehensive, its 17,000 paragraphs aiming at a final solution for every legal situation so as to avoid interpretation by judges.

The code rose out of the reforms of Frederick the Great, who felt that even in an absolute monarchy there should be prompt and impartial administration of justice to protect the subject against the arbitrary will of the prince. Yet, instead of bridging the gulf between the social classes, distinctions were carefully preserved in the interests of the state. To the nobility, from which came the army officers and the higher bureaucracy, was reserved the exclusive ownership of manorial estates. The business class was to devote itself to trade and industry—activities forbidden to the nobility. The peasantry paid the bulk of the direct taxes and supplied the army’s foot soldiers; they were, therefore, to be protected against encroachments from the lords of the manor.

Freedom of conscience and religion was granted, but the state determined which religions were permitted. Censorship was rigidly imposed on all but academics. Political dissenters were subject to severe penalties.  Encyclopedia Britannica – emphasis WWTFT

In Austria, Empress Maria Theresa followed a similar course in 1760, commissioning The General Civil code.

The Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (ABGB) is the Civil Code of Austria, which was enacted in 1811 after about 40 years of preparatory works. Karl Anton Freiherr von Martini and Franz von Zeiller were the leading drafters at the earlier and later stages of the draft. Comparable to the Napoleonic code, it was based on the ideals of freedom and equality before the law. It was divided into three major segments, following the Roman law segregation methods. It was modernized during the First World War. ABGB continues to be the basic civil code of Austria to this day and it is also still the basic civil code of Liechtenstein. Besides Austria, its influence persists in other successor states of Austria-Hungary. In Czechoslovakia it was in effect until 1949, although it had been novelized multiple times, when it was replaced by the civil code from 1950. Wikipedia – emphasis WWTFT

There are a few  striking similarities in all three instances that go beyond their shared Enlightenment heritage.  In each case, the primary purpose was to consolidate the power of the state.  Another was to remove the power of judges to apply local, or situational interpretation of the law.  Still another was the explicit mandate that all prior forms of law were to be replaced with the new, or updated versions. — no more reliance on traditions and customs developed to suit local needs and situations.  This was to be replaced by a “one size fits all” system of rules, composed and changeable only by the state.  Finally, there was an implicit assumption that the people were either incapable or not entitled to handle such weighty matters as justice, but required enlightened leadership for even the mundane aspects of societal life.

Common Law

Not all of Europe took this course. Â In spite of William the Conqueror’s efforts to regularize Anglo-Saxon law, history decided otherwise, as the English “Parliament gradually wrested power from the monarchy.”3Â

“… instead of blotting out the past, it enshrined past law and the decisions of justices as precedent. Instead of writing a new code as a plan for society, it was never codified at all. It drew its strength from the slow accretion of actions of many jurists throughout the millennium. Instead of being handed down by the edict of an emperor, it slowly wended its way through the clash of social and political forces, solidified from time to time by charters in which the king promised to obey the law. Istead of law created from the opinions of academic scholars with little experience of real life, it was tempered by men who had felt the harsh eperience of reality. As much as possible, the law set the power centers of the kingdom against each other so that one could counteract or block the attempts of another to seize power.

…

These five charters — the Charter of Liberties, Magna Carta, the Petition Right, the Bill of Rights, and the Act of of Habeas Corpus — are considered to be the unwritten constitution of British law. They embody a doctrine of “the rights of Enlightenment,” which protect the individual from oppression by the state and its apparatus. They emerged not by edict but through adversarial struggle. 4 — Links added by WWTFT

This unordered, somewhat messy, system was a far cry from the ordered, absolute and inflexible direction of the civil law course taken by the countries on the European mainland.  The chaos was somewhat taken in hand with the publication of “guides” by which jurists could find their way around all the past precedents. A judge named Thomas de Lyttleton wrote a commentary on the yearly recorded decisions, then Edward Coke followed up documented them further and was followed by Blackstone’s Commentaries.

Notwithstanding, these were mere guides for finding the right cases and precedents. Â The common law

… was never frozen into an arbitrary code. The courts instead are bound by a multitude of past decisions and statutes enacted by an elected Parliament. Common law is not written by one hand, or a committee biased by shifting current concerns.  Rather it is shaped by invisible hands working impartially over the centuries. Moreover, the fundamentals of law were decided by judges working in the common culture of Christian civilization, with reference both to the natural law and a received morality. This circumstance resulted in stability without stagnation.Â

A common law proceeding is an adversarial one, a sort of trial by combat with words and evidence instead of sword and buckler.  The judge, like a king overseeing a trial by combat, takes a neutral stance above the fray.  The prosecutor tries to make the case, but the defendant is held innocent until proven guilty. The question of guilt is decided by ordinary citizens who have no bias in favor of the interests of the state. Once declared innocent, the accused cannot be tried again for the same crime. 5

The common law does not require a “one size fits all” approach. Â It puts justice in the hands of those closest to those on the receiving end of decisions. Â In England, each shire or borough might have a slightly different set of traditions and customs, tailored over time to exactly fit the needs of that particular group of citizens. Â Laws and their attendant penalties might be enforced differently, based on what was important to that locale. Â The “invisible hands” of local jurists crafted a system uniquely tailored to local priorities. 6

A Comparison Between Civil and Common Law Traditions

James P. Lucier sums this up better than this essayist could,

These procedures of common law, which seem so self-evident as fundamental principles of justice, were all obtained through hard-fought confrontation. Â They were all aimed at the protection of the liberty of the individual. Virtually none of these protections are found in civil law proceedings where the interests of the state are paramount. Â There the defendant is guilty until proven innocent, but has not counsel sitting at the table. The judge takes an active role in shaping the outcome. The conduct of the accused is considered against the template of the public good. The purpose is to shape a remedy to protect the social order under the prescripts of the code, rather than to identify whether the action violated specific terms of the statute. 7 — emphasis WWTFT

Lucier goes on to explain that the United States inherited this tradition of adversarial governance and “local justice” from the British.  Britain has largely abandoned this tradition in 1972, by acceding to the 1957 Treaty of Rome.  What this mean is that European law takes precedence over British law.  And that the EU can even dictate what may be produced where – as in the case of Stilton cheese.

This leave the United States as the “odd man out” Â one might even say, “exceptional.” Â Why? Â International law is based on civil law and the United States has heretofore refused to acknowledge or recognize international law (different from Treaties with individual nations, which are ratified by an elected legislature, and signed into law by an elected president), except for convenience – not because we have an obligation to do so.

The United States cannot accept the validity of international law, and conforms to it as a matter of convenience, not obligation. In contrast, the international community insists that international law is an obligation, binding on all nations–even if a particular nation has not signed or ratified the treaty in question.

It has been the position of the United States that, as a sovereign state, it retains its autonomy in governing its people. Â As there is no “world government” per se, and certainly no central legislature with general law-making authority, neither is there an executive empowered to enforce such laws, did they exist. Â Finally, there is no accepted judiciary system empowered to decide cases. Â The International Court of Justice can only render advisory opinions, and has no power to compel obedience.

Lucier explains,

The term “international law,” therefore, is a contradiction in terms. Â It is “law” only by analogy; that is by comparison with true law enacted by legislatures responsible to the people and endowed with the authority to enforce it. It is “law” only to the extent that a nation-state chooses to accept it. Â True laws can be repealed or altered through the constitutional process, but there is no constitution governing the making of international law. Â Yet international legal experts would have us believe that once a nation-state accepts a principle of international law, its assent can never be revoked except through the agreement of all nations.

In summary, our entire system of government is one built on decentralized, chaotic, and adversarial systems that keep all parties in check. Â This is the reason why we have a system of checks and balances, why the accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty, and why we don’t accede our sovereignty to unelected foreign powers.

1. James Monroe And The Sources of American Exceptionalism: Modern Age, Fall 2014

2. Consider some interesting parallels to the present, the quaestor was a sort of legal advisor perhaps not dissimilar to an attorney general.  Edicts issued by the emperor could be compared with executive orders issued by the president. Legislation, like Obama Care is assembled, not by the legislators, but by unelected experts, who understand what’s best for the “common good.”

3. James Monroe And The Sources of American Exceptionalism: Modern Age, Fall 2014

4. James Monroe And The Sources of American Exceptionalism: Modern Age, Fall 2014

5. James Monroe And The Sources of American Exceptionalism: Modern Age, Fall 2014

6.. For an interesting article on how one community is trying to revive this idea, check out Justice For The People, By The People, Of The People by Stephanos Bibas and Richard A. Bierschbach. National Review, December 31, 2014 p. 36

7. James Monroe And The Sources of American Exceptionalism: Modern Age, Fall 2014

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment