The French Revolution and Communism

The American revolution was not a revolution in the usual sense. It was not an overthrow of one despotism and replacement by another. It was the principles that animated the Revolution and subsequently the nation’s founding that were revolutionary. More than 200 years of freedom and unparalleled prosperity are evidence of their validity. However, there are those who now question those principles, especially the limits that they impose on government.  These same voices argue that the Founders did not face the same issues we face today, and therefore they, and the system they established, lack relevancy. The flaw in that thinking is that although circumstances may change, human nature remains the same.  Ambition and the thirst for power are as prevalent today as they were at the time of our nation’s Founding.

The American revolution was not a revolution in the usual sense. It was not an overthrow of one despotism and replacement by another. It was the principles that animated the Revolution and subsequently the nation’s founding that were revolutionary. More than 200 years of freedom and unparalleled prosperity are evidence of their validity. However, there are those who now question those principles, especially the limits that they impose on government.  These same voices argue that the Founders did not face the same issues we face today, and therefore they, and the system they established, lack relevancy. The flaw in that thinking is that although circumstances may change, human nature remains the same.  Ambition and the thirst for power are as prevalent today as they were at the time of our nation’s Founding.

In the 20th Century, the free world had to contain and then defeat communism. But the ideology of communism was neither new nor unique. In practice as well as principle, it shares many of the characteristics of the French Revolution.

Conor Cruise O’Brien’s First in Peace offers many insights into the philosophy behind the French Revolution.

O’Brien does not make the comparison between the French revolutionary philosophy and communism in his book. He focuses instead on the historical record and the motivations behind what the French and their emissaries to the United States were seeking to accomplish. His explanation bears scrutiny for its relevance to what transpired in the 20th Century under communism.

According to O’Brien, French Revolutionary philosophy dictated that “The institutions of other countries were perceived on behalf of the French Republic as legitimate only in the degree that they resembled the pan-revolutionary archetype: the French Republic, One and Indivisible.” This belief in the quasi-moral superiority of the French Revolutionary ethic is analogous to the belief in the superiority of the communist dialectic as the necessary outcome for social development.

According to O’Brien, French Revolutionary philosophy dictated that “The institutions of other countries were perceived on behalf of the French Republic as legitimate only in the degree that they resembled the pan-revolutionary archetype: the French Republic, One and Indivisible.” This belief in the quasi-moral superiority of the French Revolutionary ethic is analogous to the belief in the superiority of the communist dialectic as the necessary outcome for social development.

O’Brien explains the behavior of France’s Minister Plenipotentiary, Citizen Genet, in the light of his belief in the innate superiority of the French Revolution. (Genet was doing his best to foment discord against Washington because of his neutrality policy in the war between Britain and France.) According to French Revolutionary thought, America and France would naturally combine in both the political and commercial realms to form an “Empire of Liberty.” Thus the French Revolution, as the sole arbiter of what constituted “legitimate government,” was at the same time a nationalist and an internationalist movement.

Marxism-Leninism is also expansionist and internationalist.  One has only to look at the famous slogan “Workers of the world unite!” or  Marx’s contention that the world’s proletariat has “a world to win.”   In Marx’s own words:

It is our interest and our task to make the revolution permanent, until the proletariat has conquered state power and until the association of the proletarians has progressed sufficiently far — no only in one country but in all the leading countries of the world.

This international focus and quasi-religious belief in the inevitability and superiority of communism  justified almost any action, and hearkens back to the events of the French Revolution.  Thomas Jefferson, in a famous letter to William Short was willing to accept, if not condone, the wanton violence that marked the French Revolution:

The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than as it now is.

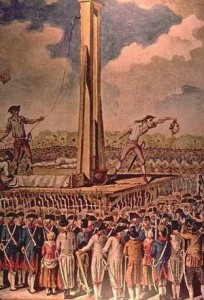

In 1793-1794 Maximilien Robespierre and the Jacobins beheaded 40,000 French citizens. Lenin himself made the comparison with the violence of the French Revolution. “It will be necessary to repeat the year 1793. After achieving power we’ll be considered monsters, but we couldn’t care less.” He and his cohorts described themselves as “glorious Jacobins.”

Alexander Solzhenitzen  observed,

Communism has never concealed the fact that it rejects all absolute concepts of morality. It scoffs at any consideration of “good” and “evil” as indisputable categories. Communism considers morality to be relative, to be a class matter. Depending upon circumstances and the political situation, any act, including murder, even the killing of thousands, could be good or could be bad. It all depends upon class ideology.

As in the Revolution in France, special attention was given to slaughtering the religious. In both ideologies, legitimacy and morality were determined by the needs of the state, and subject to change depending upon how the state defined those needs.

As in the Revolution in France, special attention was given to slaughtering the religious. In both ideologies, legitimacy and morality were determined by the needs of the state, and subject to change depending upon how the state defined those needs.

Of course, there are differences in scale between the French and Communist Revolutions. In less than a century, by conservative estimates, communism was directly responsible for at least 100 million deaths. The tactics of  both were very similar, although the means of  execution  became more efficient  over time. It is interesting to note that both encouraged reporting on one’s friends and neighbors for alleged infractions of revolutionary thought.

Ironically, many were initially misled  into thinking that the French Revolution was an extension or logical progression from the American Revolution, but they cannot reasonably be compared. However, the similarities between the French Revolutionary Government and Communist Governments are real and important. Terror was used as a tool and justified by people who viewed morality as relative to their perception of societal needs. In such a world view, there are no limits to what can be justified in the name of progress.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

In the French Revolution and the Communist revolutions the state was practically deified and the state was controlled by those who controlled the guns, inevitably dictators when there was the threat of chaos.

[Reply]

[…] quote from Jefferson is expanded on a bit by a wonderful post at What Would The Founders Think?, and deals with the animus behind the French Revolution inspired by the […]

Leave a Comment