The Johnstown Flood By David McCullough

By David McCullough

David McCullough is an exacting historian and a skilled writer. His biographies and accounts of significant structures and events are always absorbing. This reviewer had heard of the Johnstown Flood but knew little of the circumstances or the people involved. Somehow McCullough injects suspense into an event that occurred 125 years ago.Â

In 1838 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania built the South Fork earthen dam. The Western Reservoir it created was to supply the state’s canal system during dry months. The canals hauled passengers and freight and were essential to commerce and travel. But the canal system became obsolete when the Pennsylvania Railroad completed its daring construction of a rail route across the Alleghany Mountains. The state was left with a dam for which it had no use. In 1857, it sold the entire property, including the South Fork dam and reservoir, to the Pennsylvania Railroad for right of ways. “Having no use for the dam either, the railroad simply let it sitâ€.

Johnstown, located at the confluence of the Stony Creek and Little Conemaugh Rivers had much experience with flooding due to spring rains and runoff from winter snowmelt. Its proximity to the rivers, the narrowness of the valley and the steepness of the surrounding hills exacerbated the problem. The dam was to alleviate it.Â

And it was only five years after the state sold it to the Pennsylvania that the dam broke for the first time.

In the late spring of 1862, about the time the Union army under McClellan was sweating its way up the blazing Virginia and peninsula, for a first big and unsuccessful drive on Richmond, the mountains of Pennsylvania were hit by heavy thunderstorms. Hundreds of tiny creeks and runs and small rivers went roaring over their banks, and in Johnstown the Tribune ran the first of its musings on what might be the consequences should, by chance, the dam at South Fork happen to let go. Eight days later, on June 10 the dam broke.

Although no photographs were taken or records kept, the break caused little damage because the reservoir was only half full. Apparently various residents had stolen lead from the discharge pipes. The break occurred not long after the thefts. Â

After sales to private buyers, one who removed the old cast iron discharge pipes and sold them for scrap, the reservoir and dam became the property of a wealthy Pittsburgh consortium for a summer resort.

In fact, from 1857, the year the railroad took possession, until 1879, 22 years later when the Pittsburgh men took over, the dam remained more or less quietly unattended, moldering away in the woods, visited only once in a while by fishermen or an occasional deer Hunter.

By then, the reservoir was more of a pond. To enlarge and deepen the reservoir for recreational purposes, the consortium had the dam repaired and restored to its original height. The repairs were accomplished by “boarding up the stone culvert and dumping in every manner of the local rock, mud, brush, hemlock boughs and just about everything at hand. Even horse manure was used in some quantity. The discharge pipes were not replaced… “Â

The man immediately in charge of this mammoth face lifting was one Edward Pearson, about whom little is known except that he seems to have been an employee of a Pittsburgh freight hauling company that did business with the railroad and that he had no engineering credentials at all.

Despite heavy rains causing serious damage during the restoration effort no one seemed concerned, least of all the men financing the repairs. But by the end of March the reservoir, renamed Lake Conemaugh, was deep enough to be stocked with fish and for small steamboats to be assembled. The clubhouse was almost ready for its grand opening.Â

The membership of the consortium, now the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, included some of the wealthiest and most influential men in America. Many had begun with nothing but an unstoppable work ethic and a fervent desire to become rich. Â

This was the Gilded Age described by John Oller from the vantage of the pinnacles of political power in his book American Queen. McCullough’s  perspective is from the ordinary men and women who perceived the industrial expansion as jobs and hope for a better life.Â

Hardworking Germans and Welsh settled Johnstown and the Scotch-Irish came soon after to work in the mines and forges. By the start of the 1880s Johnstown and its neighboring boroughs had a total population of about 15,000. Within the next nine years the population doubled. On the day before the flood, there were nearly 30,000 people living in the Valley. With the spanning of the state by the Pennsylvania Railroad and the connection at Johnstown with the Baltimore and Ohio, large-scale development of the region’s mineral wealth became possible.Â

By 1860 the Cambria Iron Company of Johnstown was the leading steel producer in the United States. It also owned thousands of mineral rich acres around Johnstown that provided a steady supply of iron and coal. Much of the nation’s barbed wire originated in Johnstown.Â

Life was not easy, but Johnstown became accustomed to the rivers overflowing their banks every spring. From time to time residents spoke about the possibility that the South Fork dam could rupture, but, after many false alarms, most were complacent. “They had been told that the dam was properly engineered and properly maintained, and so, as long as everything went all right, they had no reason to think otherwise.â€Â

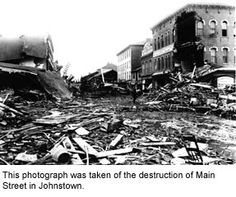

But everything was not all right. Spring rains had been continuous and unusually heavy in 1889. About 2:50 P.M. on May 31 the dam gave way. The water uprooted trees, smashed houses and bridges and, carrying train cars, mud, and rock with the rest, roared to Johnstown. What the residents heard as they were about to be inundated was not the sound of approaching water but the grinding noise of a giant hill in motion.Â

McCullough provides an almost minute-by-minute account of the flood. He follows people introduced in earlier chapters who did and didn’t live through the flood and describes the desolation of the aftermath. Survivors, shocked, injured, and cold, some barely clothed, many whose clothes had been torn off by tumbling debris, sought shelter on the top floors of the few structures still standing or clung to rooftops and floating wreckage. Painted in McCullough’s precise and affecting prose, readers perceive these scenes as clearly as though they were photographs.

Although Johnstown was isolated by the floodwaters, help was on the way as soon as the outside world learned of the disaster. Trains were chartered but unable to get through on washed out tracks. Men set out on foot and by wagon, struggling over all but impassible terrain, to deliver desperately needed supplies. Newspaper reporters were among the first to arrive, chasing what was clearly the biggest story of their careers. Â

How many perished is not known with any certainty: bodies were never found, some were simply unrecognizable. The generally accepted number is that 2,209 were killed.Â

How many perished is not known with any certainty: bodies were never found, some were simply unrecognizable. The generally accepted number is that 2,209 were killed.Â

Although the rescue effort involved thousands of people and a vast outpouring of donations, the clean up took many months before rebuilding could begin, with bodies still being discovered buried in the wreckage. Â

As for the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, efforts to sue it and the caretakers of the dam were unsuccessful. “Not a nickel was ever collected through damage suits from the South Fork Hunting and Fishing club.†Defending lawyers made the case that the tragedy was “an act of God†and that no dam could have withstood the rampaging waters (although some smaller ones downstream did). Â

But McCullough cites ample reasons to distribute blame. Along with the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, Johnstown’s leading citizens were partially responsible for the disaster.Â

In the first place, they had tampered drastically within natural order of things and had done so badly. They had ravaged much of the mountain country’s protective timber, which caused dangerous runoff following mountain storms; they obstructed and diminished the capacity of the rivers; and they had bungled the repair and maintenance of the dam perhaps worst of all they had failed – out of indifference mostly – to comprehend the possible consequences of what they were doing, and particularly what those consequences might be should nature happen to behave in anything but the normal fashion, which, of course, was exactly was to be expected of nature. …

The point, of course, was not that dams, or any of man’s efforts to alter or improve the world about him, were mistakes in themselves. The point was that if man, for any reason, drastically alters the natural order, setting in motion whole series of chain reactions, than he had better know what he is doing. In the case of the South Fork dam, the man in charge of rebuilding it, those who were supposed to be experts in such matters, had not been expert – either in their understanding of what they did or and, equally important, in their understanding of the possible consequences of what they did.

The Johnstown Flood is a riveting tale written by a superb storyteller. Like all of McCullough books, the history is as compelling as his unfolding of human courage, endurance and folly. Â

The Johnstown Flood

The Johnstown Flood The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment