The Life and Character of Stephen Decatur by Samuel Putnam Waldo

This biography of Stephen Decatur probably qualifies as obscure. The Life and Character of Stephen Decatur, like the other books by Samuel Putnam Waldo, are long out of print (other than costly photocopied versions). Fortunately, archive.org has very readable copies* scanned in. You can also attempt the OCR’d version on your Kindle or other e-reader, if you don’t mind the occasional glitch. For the best experience, the archive.org web interface is terrific. On an iPad it’s nearly (80%) as good as iBooks or the Kindle App.

On to the review.

The real value of The Life and Character of Stephen Decatur is not as a biography. To be sure it provides a good overview of Decatur’s life, but it is very superficial. It’s not a scholarly work, it’s more akin to a popular biography, and despite the author’s protestations to the contrary, it comes across as a hagiography.

It is not the business of the biographer to obtrude his opinions upon the reader but to furnish a faithful detail of facts and occurrences from which he can form one for himself.

The book is interesting as a reflection of the time in which it was written. The Life and Character of Stephen Decatur was published not long after Decatur’s death, and was sufficiently popular to merit a second edition, in which some additional material was included about the Navy Department, its ships, personnel, and cost. Also included in this second edition (the one reviewed here), were brief biographical sketches of some of the other naval heroes who were contemporaries of Decatur.

Fans of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin series will enjoy reading Putnam’s observations and accounts of some of the people featured in O’Brian’s novels. Putnam takes his reader through Decatur’s career in the navy and does a creditable job showing Decatur’s professional evolution from midshipman to navy commissioner, from the son of a noted naval officer to one of the foremost heroes in American naval history. Decatur’s fame started to accrue during his service in the Mediterranean under Admiral Preble, a legend in his own right. It is during this time that a band of close-knit officers formed a fellowship under Preble’s tutelage. Their service during this time reminded this writer of Jeff Shaara’s Gone For Soldiers and the relationship between Winfield Scott and Robert E. Lee. This formative period furnished the young republic with a fantastic cadre of capable naval officers which belied the meager size of the navy as it entered the War of 1812.

Waldo has some interesting reflections on why the navy was left to languish and why it was nearly non-existent during the early part of the Republic:

But it was necessary for American statesmen in the dawn of our national greatness, as it is now, when it is rising toward its meridian splendor, to conform their measured to the actual state of the country. It is wholly in vain to attempt to force a free and intelligent peopie into the adoption of measures which they cannot approve without surrendering the physical power they possess, and cannot execute without a sacrifice of ther real or supposed interests. When our ancestors first began to recover from the convulsive shock of the revolution, they little thought of providing defence against future invasions of our rights upon our acknowledged territory, or upon the ocean, the great highway of all nations. Having thoroughly learned the evils of a large standing army in time of peace they reluctantly retained the scanty pittance of a military force, scarcely sufficient to supply the few garrisons then scattered over our immense country.

He also has some interesting observations about the people (the Barbary Pirates) that the navy was doing battle with in the Mediterranean:

It seems to have been reserved for the American Republic, situated more than three thousand miles from these enemies of all mankind, to reduce them to complete submission — or that submission which is occasioned by fear. Indeed there is no other way for that portion of the world called Christian, to secure itself from the disciples of Mahomet, but by exciting their fear. They have such a deadly and implacable hatred against Christians, that they think they render the most acceptable service to their tutelar deity by immolating them upon the blood-stained altars of Mahomet. The most solemn treaties that can be negociated with them are bonds no stronger than a rope of sand, unless they are compelled to regard them by a force sufficient to menace them into a compliance with its provisions.

The reader is also offered a hint as to the bellicose and perhaps touchy nature of Decatur during this cruise. Although the author gives little in the way of detail, other than to suggest that the British officers in Malta might have been teasing the Americans about their puny navy, he does relate the fact that Decatur was the victor in a duel of honor with a British naval officer.

Lieut. Decatur, as ready to resent insults, as to reciprocate civilities, was aroused to a high and manly pitch of indignation at the proud and supercilious demeanor of the British officers. He could not patiently endure to see an officer of any naval power, even wink disdainfully at the sword and the epaulette he wore as the reward for his previous services. As America and Britain were then at peace, and as the more dignified of the British officers at Malta were more uniformly courteous to those of America, the conduct of a few vaunting hotspurs in the British navy, will not be minutely detailed, nor the consequences that flowed from it, animadverted upon. Suffice it to say, the determined and high minded Decatur, supported the dignity of his station, the infant glory of the American navy, and the honour of his country. The controversy eventuated in the premature death of a British officer, and the temporary suspension of Lieut. Decatur’s command.

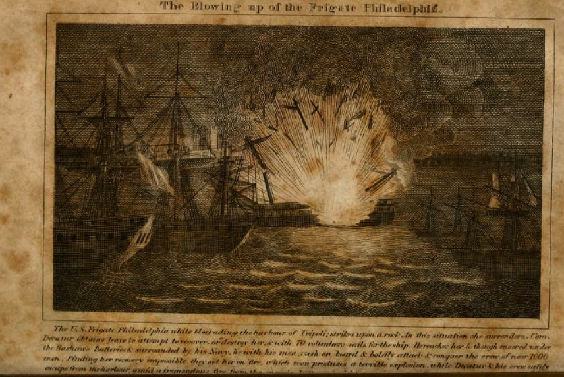

Decatur resumed his command in time to sail the captured ketch Intrepid under the batteries of the Bashaw of Tripoli to board and destroy the captured frigate, Philadelphia.**

At nightfall, Decatur and his band edged to within 200 yards of the moored Philadelphia, a ship which had ironically been commanded at one point by Decatur’s father, himself a distinguished naval officer.

At this portentous moment, the hoarse and dissonant voice of a Turk hailed the Intrepid and ordered her to come to anchor. The faithful Maltese pilot answered as previously directed and the sentinel supposed “all was well.” The Ketch gradually approached the frigate; and when within about fifty yards of her, Decatur ordered the Intrepid’s small boat to take a rope and make it fast to the fore chains of the frigate, and the men to return immediately on board the Ketch. This done, some of the crew, with the rope, began to warp the Ketch along side the Philadelphia. The imperious Turks at this time began to imagine that “all was not well.” The Ketch was suddenly brought into contact with the frigate — Decatur full armed, darted like lightning upon her deck, and was immediately followed by Midshipman Morris. For a full minute they were the only Americans on board, contending with hundreds of Turks. Lieut Lawrence and Midshipman Macdonough, as soon as possible, followed their commander and were themselves followed by the whole of the little crew of the Intrepid. A scene followed which beggars description. The consternation of the Turks, increased the wild confusion which the unexpected assault occasioned. They rushed upon deck from every other part of the frigate, and instead of aiding obstructed each other in defending her J Decatur and his crew formed a front equal to that of the Turks and then impetuously rushed upon them. It was the business of the Americans to slay, and of the Turks to die. It was impossible to ascertain the number slain, but it was estimated from twenty to thirty. As soon as any Turk was wounded he immediately jumped overboard, choosing a voluntary death rather than the disgrace of loosing blood by the hand of a “Christian dog,” as the Mahometans universally call all Christians. Those who were not slain, or who had leaped overboard, excepting one, escaped in a boat to the shore.

The “Turks” began to attack with their batteries and gunboats. Because there was no wind, and because they had insufficient men to tow the Philadelphia out, Decatur elected to destroy it and deprive the Tripolitans of their flagship.

Decatur was promoted to the highest rank then available in the navy – captain.

In a subsequent action with the same Tripolitans, his brother James Decatur, was killed after having received the surrender of Tripolitan gunboat. On stepping aboard, the gunboat’s captain shot James Decatur and in the confusion escaped with the ship. Waldo’s prose in describing the events that follow provides an example of the moral high tone he takes throughout the book.

Instinctive vengeance sudden as the electric shock took possession of his naturally humane and philanthropic soul. It was no time for pathetic lamentation. The mandate of nature and of nature’s God cried aloud in his ear — “AVENGE A BROTHER’S BLOOD.” With a celerity almost supernatural, he changed his course rushed within the enemy’s whole line with his single boat with the gallant Macdonough and nine men only as his crew!! His previous desperate rencontres, scarcely paralleled, and never surpassed in any age or country, seem like safety itself, when compared with what immediately followed. Like an ancient knight in the days of chivalry, he scorned, on an occasion like this, to tarnish his sword with the blood of vassals. His first object was to board the boat that contained the base and treacherous commander, whose hands still smoaked with the blood of his murdered brother. This gained, he forced his way through a crew of Turks, quadruple the number of his own, and like an avenging messenger of the King of Terrors, singled out the guilty victim. The strong and powerful Turk, first assailed him with a long espontoon, heavily ironed at the thrusting end. In attempting to cut off the staff, Captain Decatur furiously struck the ironed part of the weapon and broke his sword at the hilt. The Turk made a violent thrust, and wounded Decatur in his sword arm and right breast. He suddenly wrested the weapon from the hand of his gigantic antagonist; and as one “doubly arm’d who hath his quarrel just,” he closed with him, and after a long fierce and doubtful struggle prostrated him upon the deck. During this struggle one of Decatur’s crew, who had lost the use of both arms by severe wounds, beheld a Turk with an immense saber, aiming a fatal blow at his adored commander. He immediately threw his mutilated body between the falling sabre and his Captain’s head, received a severe fracture in his own, and saved for his country, one of its most distinguished champions, to fight its future battles upon the ocean.

While Decatur and the Turk were struggling for life in the very throat of death, the exasperated and infuriated crews rushed impetuously forward in defence of their respective Captains. The Turk drew a concealed dagger from its sheath, which Decatur seized at the moment it was entering his heart, drew his own pistol from his pocket, and instantly sent his furious foe —

“To his long account unanointed unaneal’d,

With all his sins and imperfections on his head.”

Thus ended a conflict feebly described but dreadful in the extreme. Capt Decatur and all his men were severely wounded, but four. The Turks lay killed and wounded in heaps around him. The boat was a floating Golgotha for the dead, and a bloody arena for the wounded and dying. Capt Decatur bore his second prize out of the harbour as he had the first, amidst a shower of ill directed shot from the astonished and bewildered enemy, and conducted them both to the squadron. On board the two prizes there were thirty three officers and men killed, more than double the number of Americans under Decatur, at any one time in close engagement. Twenty seven were made prisoners nineteen of whom were desperately wounded — the whole a miserable off-set for the blood of Lieut. Decatur, treacherously slain. The blood of all Tripoli could not atone for it, nor a perpetual pilgrimage to Mecca wash away the bloody stain.

Stephen Decatur survived his wounds and lived to fight another day.

The book is filled with this kind of descriptive phraseology, and although somewhat tiresome to the modern reader, it does illustrate the appetite for patriotic prose and the pride of the public in its early heroes.

As superficial as it is in most of the particulars of Decatur’s life, there are a number of interesting anecdotes and historical threads which Waldo does succeed in tying together.  Commodore Barron relieved Captain Preble in the Mediterranean squadron and served as Decatur’s commanding officer for a time there. Although no mention is made of this in the book, it seems likely that this where bad blood first arose between Decatur and Barron. Decatur, had, after all been a favorite of Preble’s, and it would have been difficult for Barron to assume command after all that had transpired, and all that Decatur had accomplished. It was the unfortunate Barron, a few years later, who was in command of an unprepared Chesapeake, when HMS Leopard fired a broadside into her and forced her to strike her colors in 1807. And it was Decatur, who assumed command of the Chesapeake after Barron was suspended from duty for 5 years. After an extended absence, in excess of the 5 year sentence, Barron wished to return to active duty. By then, Decatur was Commissioner of the Navy and expressed his negative opinion of the idea. Heated letters were exchanged between Barron and Decatur and the dispute was settled on the field of honor. The result, Barron severely wounded and Decatur slain.

The manner in which Waldo relates the duel and events leading up to it, is also interesting. At the time of the writing, Barron was still alive and serving in the navy. Waldo is very careful not to offend.

The Life and Character of Stephen Decatur is an interesting book on all counts, and well-worth the time to read.

*Note, the Archive.org version is the 2nd edition of The Life and Character of Stephen Decatur and has a few pages missing and some inserted in the wrong place. Google Books has a copy of the 1st and 2nd editions. The first edition is slightly different and contains somewhat less material.

**Some months prior, Captain William Bainbridge had run the ship onto an uncharted reef in the bay. After unsuccessfully trying to float the ship off the shoal, and being under attack by Tripolitan gunboats, but unable to return their fire because of the position of the ship, he was forced to strike his colors and surrender. With the coming of the tide and lightening of the ship done by Bainbridge, the Philadelphia floated free and became the pride of the Tripolitan navy. Bainbridge and his men were being held for ransom by the Bashaw.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment