The War of 1812: A WNED Documentary

WNED’s new production of The War of 1812, will premier nationally on October 10, at 9pm Eastern Time. Watch it! You’ll be glad you did.

This two hour documentary is full of interesting facts and tremendously well done. For most Americans, if they know anything at all about the nation’s “second war of independence,” they associate it with about 4 major points.

- Old Ironsides aka The USS Constitution

- The Battle of New Orleans, thanks to country music singer Johnny Horton

- “Don’t Give Up The Ship,” now more attributed to Commodore Perry than to Captain Lawrence of the Chesapeake

- The Star Spangled Banner, written by Francis Scott Key while captive on a British ship.

In Britain this war is almost completely unknown. Their focus was on France and Napoleon and modern Britons know even less about it than modern Americans. For Canada, however, it’s a different matter.  This war assumes greater importance. This film’s major focus is on the Canadian invasions and the Canadian perspective is heavily emphasized.

The War of 1812 is packed so full of information, that the viewer gets the idea that much more ended up on the cutting room floor than actually made it into the final release. (There is a wealth of additional materials at the PBS website, so at least it’s not all lost.) The documentary starts off at a gallop and maintains a breakneck pace, covering topic after topic at lightning speed. It begins with an explanation of the events leading up to the war and a description of the political climate in the first part of the 19th century – 1800 – 1810.

Britain was in the midst of a massive European war with France and was manning its navy by snatching American citizens and pressing them into service. Over 6000 American seamen were “impressed” into the British navy.

The British issued their “Orders In Council” which severely restricted American shipping, in effect requiring licensing  to conduct trade. This series of legislative decrees restricted neutral trade and enforced a naval blockade of Napoleon’s France and its allies. The French responded in kind with their Milan Decrees. This put a severe damper on American shipping.

The film also briefly covers the Chesapeake – Leopard affair of 1807.  (Please see this post for more details.)

In spite of these transgressions against American sovereignty, the country was by no means unified in desiring to go to war with Great Britain. America was neither militarily nor financially prepared for war with England. The US Navy was minuscule in comparison with that of Britain, as was this country’s army.

Nonetheless, the Congress of 1810 saw an influx of war hawks who were men of the generation following those of the Revolution. These were men like John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay, and they were eager to reclaim the nation’s pride and go to war with Britain, regardless of the cost.

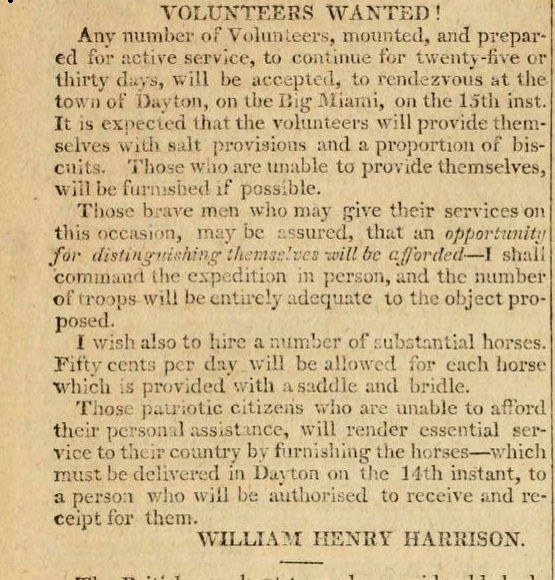

Meanwhile, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh was inveigling with the British and trying to unify the various Indian nations in their own confederacy, while his nemesis, William Henry Harrison, was trying to sign treaties with all of the individual tribes, and as the film says, “pick them off one by one.” Tecumseh refused to sign such a treaty. The two men met in August of 1810 at Harrison’s home. This meeting was a tense affair, Tecumseh made no bones about his disregard for the objectives of the American settlers.

In 1811, while Tecumseh was away working on a confederacy of Indian nations, Harrison took a thousand troops to attack Prophetstown.  The Indians attacked at Tippecanoe and inflicted considerable damage on November 7, 1811. At best, this battle was a draw. Yet Harrison’s reports  to Washington billed it as a glorious victory. Thus a myth, like many others surrounding the War of 1812, was born.   The day after the battle Harrison’s troops burned Prophetstown to the ground. In the village, they found British weapons. This outraged the frontier press and garnered support for  advocates of war with Britain. This put pressure on Madison, who sent a message to Congress laying out our grievances with Britain, on June 1, 1812.

The hawks in Congress got their wish. On a vote in the House of 79 – 49 and in the Senate of 19 – 13, Congress declared the country to be in a state of war with Britain.

Nevertheless, the country was divided. The western territories were enthusiastic, but the Federalists in the north were not. Their livelihoods were  directly affected, since they had a great deal of trade with English merchants.

One of the historians interviewed in the course of this excellent documentary was Anthony S. Pitch, author of The Burning of Washington, a phenomenal book reviewed here at WWTFT. (Mr. Pitch also kindly consented to an interview with WWTFT here.)  Mr. Pitch describes some of the events in Baltimore surrounding the mob attack on a Federalist newspaper editor named Alexander Hanson. Unfortunately, much of what he had to say did not make it into the film. However, you can read more about this incident in Pitch’s book or in the WWTFT book review.  Pitch remarks that the lesson to be taken from this event is that:

What happened in Baltimore, in those early days of the war of 1812, is a lesson in how you should not subdue dissent even during warfare, because a mob can get out of control and destroy the very values which you are trying to uphold.

One of the points stressed in this documentary is the affect that the War of 1812 had on Canada. The Canadians knew that a declaration of war must necessarily be followed by an invasion, since Canada was the nearest land mass belonging to Britain. The Americans gravely misconstrued the mood in Canada and thought, as Jefferson predicted, that it would be “a mere matter of marching.” Madison thought that the Canadians would welcome the US troops as liberators, and what’s more that Britain wouldn’t fight very hard to defend the Canadian territory. They were wrong on all counts.

The war starts off very inauspiciously indeed. Historian Douglas DeCroix explains that the American government was wholly inept in its communications with the frontier. It actually used regular mail to inform the forts in Michigan that war had been declared. Since the British forces knew the war had been declared and the Americans did not, they were able to take the strategic Mackinac Island fort.

As the summer of 1812 progressed, things didn’t get any better. Madison approved a plan for a three-pronged invasion of Canada. The leadership provided by the American generals was terrible.  Conversely Canada had an able administrator in Governor Prevost and the brilliant military leadership of Isaac Brock.

The film provides a great anecdote about Brock that sounds like the inspiration for a scene in one of the early books in C.S. Forrester’s Horation Hornblower series.

The film provides a great anecdote about Brock that sounds like the inspiration for a scene in one of the early books in C.S. Forrester’s Horation Hornblower series.

When he first joined the 49th Regiment of foot, in the regiment was a famous duelist. This man insulted Brock. Brock insulted him right back. So this man challenged Brock to a duel. Brock chose pistols to be fired over a handkerchief. Not a distance of 30 paces, but over the width of a handkerchief. The duelist backed down, and being disgraced, had to leave the regiment.

Brock had a massive area to defend and not much of a force to do it with. But, unlike the American troops, his men were veterans.  One of the more interesting aspects of the film is the use of diaries and letters from some of the participants on both sides. These were men like Shadrack Bifield of the Canadian forces and William Atherton of the US.

William Hull was chosen by Madison to lead an army from Detroit.  Brock made use of the Indians to augment his forces. Tecumseh and Brock became good friends. They immediately pressed an attack on Detroit. In spite of being safely ensconced behind 11 foot walls, with superior forces, Hull had an inordinate fear of the Indians. Tecumseh marched his troops around the fort multiple times to make it look like he had more men than he actually did. Meanwhile, Brock dressed Canadian militia in the surplus uniforms of regulars. Hull disintegrated and ignominiously surrendered. This is the only time a US city has raised a white flag of surrender.

Ultimately Hull was court-martialed and sentenced to be shot. Madison sustained the court-martial, but not the execution.

Thus the first of the three-prongs of invasion ends in disaster. The second was to take place from Lewiston to Queenstown, across the Niagara River. Steven Rensselaer, a wealthy New York politician, is given the command of this expedition. He had no experience. Isaac Brock was everywhere. He sailed down Lake Erie and took command of a mishmash of forces, to defend the Canadian version of North America. On October 13, 1812, a portion of the American army crossed the Niagara and took the Queenstown Heights. Here General Brock was killed. This galvanized the British army to avenge their fallen general, but it was the Indians who crept up on the Americans commanding the heights and turned the tide. Meanwhile the Americans failed to send reinforcements and the battle was lost.  It was interesting to discover that John Beverly Robinson was a British artillery officer in this battle. Robinson’s father had been friends with John Jay and had to leave the United States during the American Revolution. (See the review of Maya Jasanoff’s Liberty’s Exiles here.) This marked the second defeat of the invading Americans. The British took almost 1000 prisoners in this battle, but lost Isaac Brock.

The third time was no charm. The third American army of invasion was targeted at Montreal. It was commanded by an old general named Henry Dearborn. Things were so confused that his two columns of troops ended up firing on each other by mistake. Two-thirds of his militia troops refused to cross the border and they never engaged the enemy. The invasion never happened at all, Dearborn called it off. It was another unmitigated disaster.

The three land-based attacks failed miserably, but American morale was lifted by three seemingly improbable naval victories in quick succession.

On August 19, 1812, the USS Constitution took HMS Guerrier. A few weeks later, she took the British Frigate HMS Java and the USS United States took HMS Macedonia.

As the film progresses along the timeline of the war Tecumseh’s benignity is contrasted with Harrison’s ruthlessness.

In early 1813, a British force lead by Colonel Henry Proctor captured approximately 80 American soldiers at River Raisin.

Although the British forces failed to take Fort Meigs, it was followed by a disastrous battle at Stony Creek. One of the historians sums up the events as a microcosm of the paradoxes of the entire war.

The Battle of Stony Creek is, in many ways, representative of the War of 1812 in microcosm. The American commanders are captured, the British commander gets lost in the woods, the Americans technically are defeated, but they retain the field, the British are victorious, but they retreat.

Back to the naval war, the documentary also covers the battle between the Shannon and Chesapeake – for more details on this, please refer to this WWTFT post or perhaps this one. It is in this epic single ship action that Captain Lawrence utters the famous phrase “Don’t Give Up The Ship,” before he dies, and the USS Chesapeake is captured.

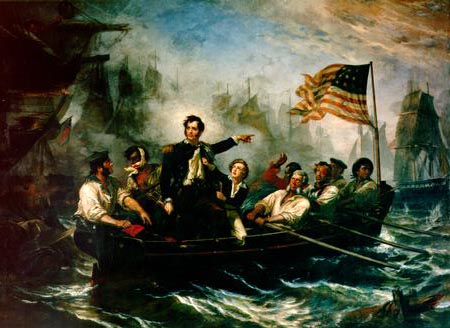

Later in that same month of September 1813, Oliver Hazard Perry conducted a successful battle against Barkley on Lake Erie. Perry’s flagship was the USS Lawrence. His report on this important victory was famously brief:

We have met the enemy and they are ours; two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop.

The historians in the film point out that there were numerous myths that arose out of this pointless war. William Henry Harrison and Andrew Jackson made names for themselves and both men rode the glory of their accomplishments to political success. A great number of Americans thought that Jackson’s victory at New Orleans was the decisive stroke, even though the treaty had already been signed. The Canadians developed their own mythology about the invincibility of their militia and the unimportance of a regular army.  Additionally, many feel that the seeds of Canadian independence were sown in the War of 1812.

In the words of a British soldier at the end of the war, The War of 1812 was a “hot and unnatural war between kindred people.” In the end, the United States lost no territory, and Britain gained none. However, America learned of the importance of self-defense, gained a national psyche and a host of heroes.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

1 comment

I look forward to more on this subject. Thank you JH

[Reply]

Leave a Comment