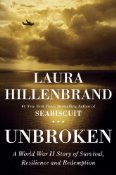

Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand

This reviewer comes late to Laura Hillenbrand’s book, Unbroken, published in 2010. The book jacket describes the contents as “A World War II story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption.†It is all of that and more. The protagonist is Louis Zamperini who, at the hands of his Japanese captors, survived torture, starvation and sadism that plumb the depths of human evil. It is also the story of the men who endured those horrific conditions with him.

This reviewer comes late to Laura Hillenbrand’s book, Unbroken, published in 2010. The book jacket describes the contents as “A World War II story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption.†It is all of that and more. The protagonist is Louis Zamperini who, at the hands of his Japanese captors, survived torture, starvation and sadism that plumb the depths of human evil. It is also the story of the men who endured those horrific conditions with him.

Zamperini was singled out for “special†treatment. As a world famous runner he was a living challenge to the Japanese claim to be “the sole superior race of the world.†But in addition to proving that he was unequal to his captors, they wanted him to further their propaganda efforts by making radio broadcasts extolling Japan and its treatment of POWs. He refused, with predictable results.

But that is getting ahead of the story. To fully understand Zamperini it is necessary to begin with his childhood and that is what Hillenbrand does. As a child he was the scourge of his Torrance, California neighborhood. He picked locks to steal sweets from a bakery and pies from neighbors’ kitchens. He figured out how to get coins out of pay telephones. He stole scrap metal from a junkyard and sold it back to the unsuspecting owner the next day. To hide the evidence of his thievery when the police invariably came his way, he stashed his loot all over town. He was also an inveterate practical joker. When he bragged of his various exploits his stories usually ended with “…and then I ran with the wind.†His parents could not control his inventive mind or stop his dare devil exploits.

In a childhood of artful dodging, Louie made more than just mischief. He shaped who he would be in manhood. Confident that he was clever, resourceful, and bold enough to escape any predicament, he was almost incapable of discouragement. When history carried him into war, his resilient optimism would define him.

As he grew older, the impish kid began to look more like a juvenile delinquent. His older brother Pete worried that Louie was headed for serious trouble unless he was distracted from his determination to break all conventional boundaries. That distraction, Pete decided, was running. By necessity, Louie was adept at it.

Pete saw incipient talent and forced Louie to train. Louie hated running but loved the applause when he won. But in the summer of 1932, he rebelled against the regimen set forth by Pete. He ran away, hitchhiked to Los Angeles, hopped a freight train and had a thoroughly miserable time. Cold and hungry, no money and no prospects, Louie went home and became a runner.

Pete accelerated Louie’s training and encouraged him to enter track meets.

All of the effort that he’d put into thieving he threw into track. On Pete’s instruction, he ran his entire paper route for the Torrance Herald, to and from school, and to the beach and back. …

To expand his lung capacity, he ran to the public pool in Redondo Beach, dove to the bottom, grabbed the drain plug, and just floated there, hanging on a little longer each time. Eventually, he could stay underwater for three minutes and forty-five seconds. People kept jumping in to save him.

Louie, a.k.a the Torrance Tornado, broke track records at Torrance High. He set a world interscholastic record in 1934 for the mile. At USC he won a spot on the 1936 Olympic team and went to Berlin. He was the youngest distance runner ever to make the team and although he won no medals he would be a contender at the 1940 Olympics in Finland. He was training hard when Hitler and his Soviet ally swept across Europe. The Olympics were cancelled.

Louie, a.k.a the Torrance Tornado, broke track records at Torrance High. He set a world interscholastic record in 1934 for the mile. At USC he won a spot on the 1936 Olympic team and went to Berlin. He was the youngest distance runner ever to make the team and although he won no medals he would be a contender at the 1940 Olympics in Finland. He was training hard when Hitler and his Soviet ally swept across Europe. The Olympics were cancelled.

Drafted, Louie ended up in the Army Air Corps where he was trained as a bombardier. Flying bombing missions in B-24s, his squadron dodged flak and fighter bullets, not always successfully as the casualty lists reveal. Once the plane Louie rode returned looking like a large Swiss cheese. Louie counted 594 holes.

But the Japanese did not bring the B-24 plane carrying Louie down in the Pacific. It was mechanical failure. Out of 11 crew-members, only three survived; bombardier Louis Zamperini; pilot Russell Allen Phillips; and tail gunner, Francis McNamara

On their 33rd day at sea McNamara died. Louie and Phillips endured starvation, dehydration, a typhoon and attacks by sharks that rubbed against the raft and tried to dislodge the occupants. Miraculously, the two men were not hit when a Japanese bomber pilot strafed them. The same cannot be said of the raft. It received numerous punctures and constantly threatened to deflate despite Louie’s desperate patching. That the two managed 47 days at sea, with no food or water beyond what their ingenuity occasionally provided, is an epic tale of survival by itself. But it is only the prelude to what they would endure after capture.

After floating thousands of miles when they finally reached land it was the Japanese occupied Marshall Islands. They were taken prisoner by Japanese sailors.

Whether in the Pacific islands or after transfer to Japan, rations were pitifully inadequate and drinking water was scarce and contaminated. Dysentery and beriberi coupled with the privations already suffered on the raft turned both men into walking skeletons. Daily beatings and humiliations at the hands of sadistic guards, and slave labor in the service of the Japanese war effort winnowed their souls.

.

Much has been written about the barbarous behavior of the Japanese in World War II. Hillenbrand explains that the guards in the POW camps were, with few exceptions, the dregs of Japanese society: misfits and psychotics gorging on their newfound power.

…(T)he guards sought to deprive them of something that had sustained them even as all else had been lost: dignity. This self-respect and sense of self-worth, the innermost armament of the soul, lies at the heart of humanness; to be deprived of it is to be dehumanized, to be cleaved from, and cast below, mankind. Men subjected to dehumanizing treatment experience profound wretchedness and loneliness and find that hope is almost impossible to retain. Without dignity, identity is erased. In its absence, men are defined, not by themselves, but by their captors and the circumstances in which they are forced to live. One American airman, shot down and relentlessly debased by his Japanese captors, described the state of mind that his captivity created: “I was literally becoming a lesser human being.â€

…Louie and Phil learned a dark truth known to the doomed in Hitler’s death camps, the slaves of the American South, and a hundred generations of betrayed people. Dignity is as essential to human life as water, food, and oxygen. The stubborn retention of it, even in the face of extreme physical hardship, holds a man’s soul in his body long past the point at which the body should have surrendered it. The loss of it can carry a man off as surely as thirst, hunger, exposure, and asphyxiation, and with greater cruelty…. degradation could be as fatal as a bullet.

Louie wound up in the hands of a psychotic prison official, known as “The Bird,” whose self-imposed mission was to break Louie’s spirit. The tortures he inflicted were so horrific that it is almost beyond understanding how anyone, let alone someone in Louie’s debilitated condition, could live through them. But no matter how brutalized, Louie remained “unbroken.â€

The remainder of this riveting book is devoted to the POWs liberation at the end of the war and their lives back home. But freedom did not erase the rage and fear suppressed during those long months in Japanese hell. Reintroduction to the civilized world was emotionally harrowing and for some former POWs, fatally so. That’s where the redemption comes in.

This reviewer strongly recommends this book. Hillenbrand is a compelling writer and she tells an extraordinary story. There is enough suspense and action between these covers to fill several novels. Only the tale she tells is true.

Reviewers note: Louis Zamperini, at this writing, is still alive and still feisty at 96 years of age.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

1 comment

The true stories are always the best! I loved this book even more than you Martin.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment