West of the Revolution An Uncommon History of 1776 By Claudio Saunt

From the Introduction to West of the Revolution:

From the Introduction to West of the Revolution:

The American Revolution so dominates our understanding of the contents early history that only four digits – 1776 – are enough to evoke images of periwigs, quill pens, and yellowing copies of the Declaration of Independence. Yet the colonies that form the Continental Congress and filled the ranks of the Continental Army (paying men in continental currency) made up only a tiny fraction of the actual continent – just under 4% of North America, to be more precise.

Claudio Saunt means to remedy that lack with this sweeping account of what was happening in the other 96% on or around 1776. A date that had immediate as well as long-term ramifications far beyond America’s Eastern seaboard. Independence opened the West to explorers, speculators, trappers, traders, settlers and missionaries. They set out to build settlements, make fortunes, establish trade, and convert the heathen (not necessarily in that order). It was risky going at best.

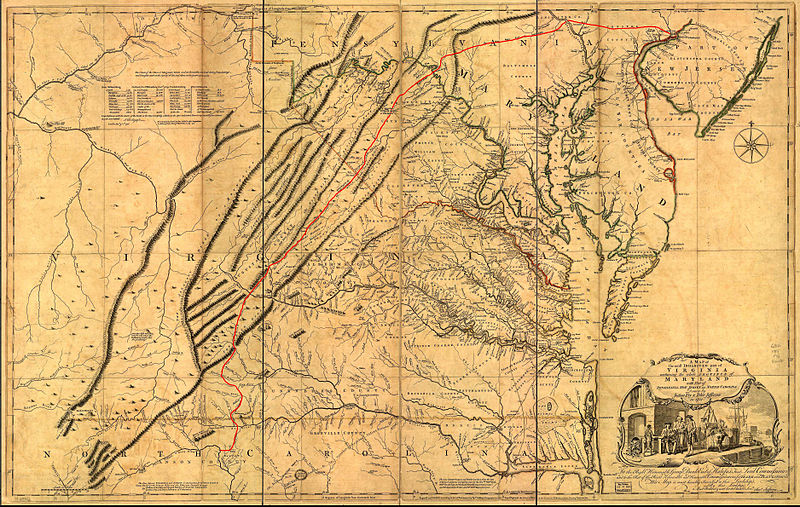

Even armed with the best maps of the era, speculators were largely in the dark about what lay west of the Appalachians. George Washington consulted Joshua Fry’s map of the most inhabited part of Virginia. It left the Western waters unchartered but helpfully identified a “high mountain” from which travelers could espy a gap through the Appalachians. As late as the Revolutionary war, colonists had no better map of the Kentucky region then John Mitchell’s 1755 small-scale representation of North America. What little detail it offered was highly misleading. No cartographer made more than a half attempt to publish a map of the area until 1778, long after speculators had claimed the land many times over.

Washington’s early Western adventure –as a major in the British militia of Virginia he crossed the Allegheny Mountains to command the French to withdraw from the Ohio region– convinced him that the destiny of the United States was tied to expansion. He personally invested in Western lands and labored to see the West linked to the East Coast.

At the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War (that Washington’s adventure helped start), diplomats from France, Britain, and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris in1763. They divided a continent about whose interior physical features they knew little and its native populations even less. Saunt unravels the unforeseen consequences of those divisions to the natives and to European newcomers who were tasked to live by them.

Some tribes benefited from increased trade opportunities brought about by the new boundaries, while others, like the Creeks “had nothing good to say about the Treaty of Paris. Creek leaders pointedly told he governor of Georgia, ‘they are surprized (sic) how People can give away land that does not belong to them.’â€

The author describes how the imperial powers attempt to preserve trade monopolies based on the boundaries were frustrated by the natives (sometimes aided by the representatives of those very powers) who followed economic imperatives rather than imperial administrators.

One chapter details Russia’s Aleutian Islands incursions. By the 1670s, Russian trappers had exhausted the supply of high value fur-bearing animals in many parts of Siberia and turned their attention to the Aleutian Islands. Fox and seal were plentiful there as were sea otters whose pelts were even more valuable. The Russian hunters forced the Aleuts to help them. Violence between the two groups grew with the Aleuts getting the worst of it. The Russians, despite their disdain for the “uncivilized†Aleuts admired the baidarka, (the native boat,) because it was so perfectly adapted to the difficult Aleutian environment.

The watertight vessel was as functionally advanced as it was beautiful, and even today sailors marvel at its unequaled design… Constructed with ‘infinite toil and trouble,’ the fourteen-foot- long single-hatch variety was framed in cedar, joined with flexible baieen strips and bone inserts, and sheathed in translucent seal or sea lion skins to reduce drag and improve water resistance, all but the final central seam were on the inside. A split bow (like a tuning fork) and a three-part keel made the narrow boats extraordinarily fast and flexible. Light enough to be carried by a single hunter, the 30-pound vessels could nevertheless transport over 400 pounds of catch through pounding waves high surf.

This description is augmented by one of the many fine illustrations scattered throughout the book.

Russian fur trappers hunted sea otters on the West Coast as far as San Diego, prompting Spain to attempt to forestall Russian expansion (and protect its interests in Mexico) by establishing colonies there.

West of the Revolution explores nine American locations on or around 1776 but pays little attention to the Revolutionary War or to the individuals involved. The only time they are mentioned is when the author wants to tie one of the nine to the Revolution. For example he writes:

On September 17, the day after Washington’s troops held their position on Harlem Heights in Manhattan, the Spanish took formal possession of San Francisco Bay. Two missionaries performed the solemn mass, church bells were sounded, and cannons and muskets fired. The San Carlos, anchored offshore, responded in kind with its swivel guns. All felt “joy and happiness,” wrote the missionary Francisco Palou, though local residents vanished during the festivities and did not appear again for several days. In early October, another ceremony marked the official founding of the mission. ‘The only ones who did not enjoy this happy day,’ Palou noted, ‘were the heathens.’

Another connection between distant places took place at Arkansas Post, originally founded by the French but by1775 in Spanish hands. One of its wealthiest residents, a Frenchman named Francois Menard, won a contract to supply ten thousand pounds of tallow to Havana. To fulfill this contract required roughly 150 bison. Each animal would yield on average 75 pounds of tallow if slaughtered when bison bulls were “in their Fat.†The native people, having already found a ready market for tallow among European traders, slaughtered bison at the optimum time, leaving the rest of the carcasses to rot. To fulfill Menard’s contract the tallow was packed in boxes and floated down the Mississippi to be shipped by boat across the Gulf of Mexico to the Naval Shipyard in Havana. There it was slathered on the slips used to launch the ships of the line built there. “Underlying the entire operation was bison tallow, produced and sold by native peoples in the heart of North America.â€

Claudio Saunt’s panoramic account includes such sidebars as the effect of the near extinction of beavers on the North American ecosystem in 1900 due to the great popularity of beaver hats in 17th century Europe. Saunt packed an amazing amount of information in 211 pages.

West of the Revolution provides readers with an enlarged perspective of that seminal year in American history and the illustrations help to locate the reader in the political geography of the time. I suspect most readers, like this reviewer, did not know what they didn’t know before reading West of the Revolution.

Â

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment