What Hath God Wrought by Daniel Walker Howe

What Hath God Wrought* The Transformation of America, 1815 – 1848 by Daniel Walker Howe

What Hath God Wrought* The Transformation of America, 1815 – 1848 by Daniel Walker Howe

To say this book presents a panoramic account of the years in the subtitle only hints at what is between the covers. Much has been written about the Civil War period and, more recently, the Revolutionary War period, but the years between have not received the attention they deserve. Howe makes up for the deficit.

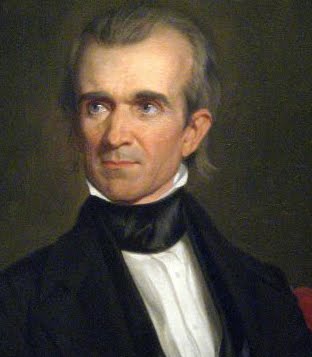

This is an astonishing book for both its breadth and depth. All the major players are here, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, James Polk, and John Calhoun to mention a few. Each had his own vision for the developing nation shaped by ambition, personality, political orientation and sectional issues, slavery being the most challenging. When faced with difficult choices they did what they believed best for the nation. Martin Van Buren comes to mind as an exception. But it is Adams and Jackson who represent the polar opposites of American political life. Howe clearly comes down on the side of Adams to whom he dedicated his book.

Along with conventional political, diplomatic and military accounts, Howe weaves the social, economic and cultural milieu that shaped events. He includes the emergence of a distinctively American literature represented by authors Henry David Thoreau, James Fennimore Cooper, Walt Whitman among others.

“What Hath God Wrought†is a long book, but Howe’s mesmerizing prose is more than equal to the task of holding readers’ interest through all 855 pages. In this reviewer’s experience, the rewards far exceeded the time invested. It is difficult to encompass the scope and scholarship of Howe’s book in a review. One can only hope that this “bird’s eye view†will entice readers to take the plunge.

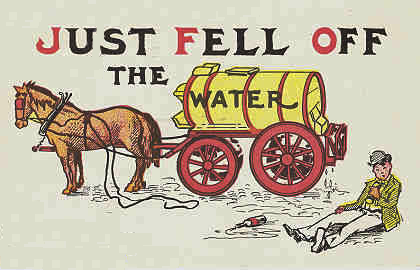

An added enticement is the author’s occasional excursion into the origin of phrases that are embedded in the culture but whose sources are shrouded in the past. While discussing voluntary religious organizations as workshops for participatory democracy, the author explains why famous revivalist Lyman Beecher made temperance a Christian cause.

“Americans in the early nineteenth century quaffed alcohol in prodigious quantities. In 1825 the average American over 15 years of age consumed seven gallons of alcohol a year, mostly in the form of whisky and hard cider.â€

Beecher did not suggest legal prohibition; his goal was to change attitudes. Temperance volunteers paid reformed alcoholics to drive the “water wagon†through towns and encourage converts to jump aboard.

Similarly, Howe provides background for familiar products. He tells of two immigrant brothers-in-law, William Procter and James Gamble, who formed a partnership to make soap for market using the lard produced by Cincinnati’s large meatpacking industry, “initiating the replacement of an article of household manufacture with a mass consumer product.â€

It is almost beyond present-day powers of imagination to picture the vast, sparsely settled tracts of land that was America – so isolated by time and distance that wars ended while armies battled on for causes already won or lost. The Battle of New Orleans on Jan.1 1815 was fought after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent that ended the War of 1812. The treaty was signed on Christmas Eve, 1814.

Howe describes life in 1815 America as “dirty, smelly, laborious and uncomfortable,†but notes that it compared favorably with European peasants of the time. The majority of Americans were farmers and most worked land they owned. In Howe’s words, they considered themselves “citizens not subjects†and were not shy about voicing their rights.

“This was not a relaxed, hedonistic, refined or indulgent society…The man who got ahead in primitive conditions did so by means of innate ability, hard work, luck and sheer will power.â€

Self-sufficiency was not a choice. It was a necessity, and it molded the nation’s character.

Howe’s unifying theme is the way simultaneous technological revolutions in transportation and communication transformed America. The introduction of steamboats, canals, turnpikes and railroads, shortened travel time and reduced the cost of moving goods, greatly facilitating commerce and raising living standards.

There is a case to be made, and Howe makes it, that the far reaching consequences of these advances “rivaled and probably exceeded in importance, those of the revolutionary ‘information highway’ of our own lifetimes.â€

“During the thirty-three years that began in 1815, there would be greater strides in the improvement of communication than had taken place in all previous centuries.â€

The communication revolution also gave rise to a vastly enlarged print media making possible nationwide political parties, the growth of the women’s suffrage movement and the spread of abolitionist sentiment.

The weekly “Niles’ Register,†frequently cited by Martin on these pages, is described as “of particular value in creating an informed public.

“This periodical constituted the closest thing to a nonpartisan source and provided, as it boasted, ‘political, historical geographical, scientific, statistical, economical and biographical information.’ Historians as well as contemporaries have reason to be grateful to Hezekiah Niles.â€

What impressed this reader is that whatever the developing nation needed to thrive, a creative people invented or built. However, as the author points out in another interesting aside:

â€Improvements in travel and transportation also had their downside: the spread of contagious disease. Endemic in the Ganges River Valley of India, cholera moved along trade routes in the early nineteenth century to Central Asia, Russia, and across Europe from east to west. In the summer of 1832, it crossed the Atlantic with immigrants to Canada and the United States. Cholera hit the great port cities of New York and New Orleans hardest, but the disease spread along river and canal routes exacting a heavy toll wherever crowded or unsanitary conditions prevailed.â€

Although the period Howe writes about is usually referred to as the Age of Jackson, (and he devotes a great deal of ink to the seventh president’s two terms), Howe insists it’s a misnomer because it ignores the contributions of the Whigs whom he characterizes “as economic modernizers, as supporters of strong national government, and as humanitarians more receptive than their [Democratic] rivals to talent regardless of race or gender… “

Howe faults Jackson, whose influence shaped James K. Polk’s presidency, for populating government with inexperienced patronage hacks whose only virtue was loyalty to Jackson. He blames Jackson’s foolish closing of the Second Bank for the recession of 1837, and condemns his policy of Indian Removal because it “set a pattern and precedent for geographical expansion and white supremacy.†…â€

“White supremacy, resolute and explicit, constituted an essential component of what contemporaries called ‘the Democracy’ – that is, the Democratic Party.”

This reviewer has to marvel at the epidemic of amnesia that expunges that record from the minds of today’s Democrats who seem intent upon painting political opponents with the tainted brush of the Democrat past.

But as William J. Cooper points out in his book, “We Have the War Upon Us: (reviewed here)â€

“’The supreme task of the historian and the one of most superlative difficulty, is to see the past through the imperfect eyes of those who lived it, and not with his own omniscient twenty-twenty vision.â€

Among white southerners of the mid-nineteenth century the prevailing view was that there was no contradiction between faith in liberty and the existence of slavery. In fact, white southerners defined liberty as encompassing their right to own slaves and to determine the fate of the institution. Common economic interests united southern plantation society into a politically powerful and socially cohesive group. “By 1815 they had held the presidency for twenty-two of the past twenty-six years and would control it for all but eight of the next thirty-four.â€

Howe condemns Polk’s instigation of the war with Mexico as immoral. Robert Merry’s book, “A Country of Vast Designs,†(reviewed here) presents a different view. Merry finds justification for the war in the Texas-Mexico boundary dispute which Howe views as a transparent ruse to acquire Mexican territory. Where Merry cites Polk’s accomplishment of establishing a content-spanning nation “from sea to shining sea,†Howe views Polk far more critically. Which is to say that Howe views the expansionism of both Jackson and Polk negatively and his book makes a cogent case in support of that view. However, he does not allow it to shadow fact.

Howe condemns Polk’s instigation of the war with Mexico as immoral. Robert Merry’s book, “A Country of Vast Designs,†(reviewed here) presents a different view. Merry finds justification for the war in the Texas-Mexico boundary dispute which Howe views as a transparent ruse to acquire Mexican territory. Where Merry cites Polk’s accomplishment of establishing a content-spanning nation “from sea to shining sea,†Howe views Polk far more critically. Which is to say that Howe views the expansionism of both Jackson and Polk negatively and his book makes a cogent case in support of that view. However, he does not allow it to shadow fact.

He writes that Polk’s expansionist policies “extended the domain of the United States more than any other president.†The future states of Texas, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Washington, and Oregon, as well as portions of what would later become Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, Wyoming, and Montana were the result.

Similarly, Howe observes that Jackson’s repugnant Indian Removal policies opened 25 million acres of land to white settlement and prompted an enormous influx of immigrants seeking opportunity for better lives.

The author contrasts Jackson and Polk with John Quincy Adams whom he describes as a man of principle. Readers will note that Howe dedicated his book to Adams.

In an eerily familiar account, Howe describes the election of 1824 when the House of Representatives chose John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson for president. (None of the four candidates obtained a majority of Electoral College votes.) Jackson’s followers were furious because Jackson bested Adams in the popular vote.

The Democratic Party was then formed with the goal of putting Jackson in the White House in 1828. The author describes that presidential campaign as “probably the dirtiest in American history. It seems only fair to observe that while the hostile stories circulated about Adams were largely false, those about Jackson were largely true.â€

Rather than debate policy, Jacksonians harped on the ‘corrupt bargain’ that robbed the people of their preferred candidate.â€

Jackson was extolled as “a hero, a leader of stern virtue, and a frontiersman who had made his own legend.“ Shifting the focus of the campaign from programs to personalities generally benefited Jackson.

Any resemblance to contemporary persons and events may be accidental, but are nonetheless compelling.

Jackson enjoyed the support of many (not all) journalists; the most important was Amos Kendall. Kendall “honed his sense of how to shape a political message for the public. He formulated the rationale for the spoils system as “rotation in office…” Kendall exemplified the observations about political speech made by George Orwell more than 100 years later. It might also be said that the Jackson campaign initiated the cult of personality.

The repercussions of 1824 and 1828 are with us still. The two party system took root when the Whig Party formed in opposition to Jackson. The Founders abhorred the two-party structure, but it has endured virtually unchanged to today.

The repercussions of 1824 and 1828 are with us still. The two party system took root when the Whig Party formed in opposition to Jackson. The Founders abhorred the two-party structure, but it has endured virtually unchanged to today.

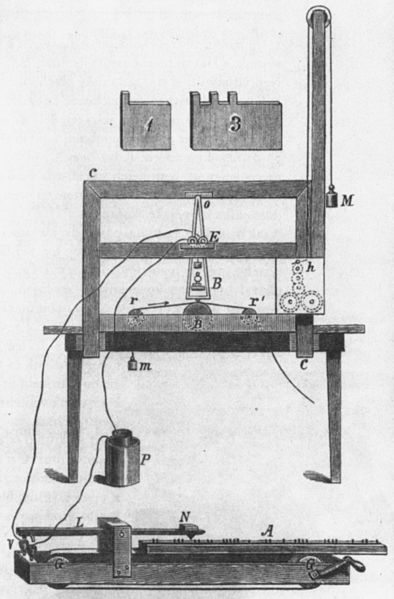

The title of this book, is taken from the biblical quotation sent by Samuel F. B. Morse in the initial demonstration of the telegraph on May 24, 1844. It expresses both the inventor’s heart-felt Christian faith and the influence and importance of religion in American history. Throughout the book the author emphasizes the importance of religious organizations not only as workshops for democracy, but because they molded a uniquely American identity.

Howe points out that the message Morse transmitted did not include a question mark, which Morse later added when transcribing the message. Howe does not include one in the book’s title.

“The misquotation had its own significance. Morse’s question mark  unintentionally turned the phrase from an affirmation of the Chosen People’s Destiny to a questioning of it. What God had Wrought in raising up America was indeed contested, in Morse’s time no less than it is today…â€

*What Has God Wrought is part of the Oxford History of the United States series of 12 volumes.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment